Posted on Thu., Jan. 8, 2015 by

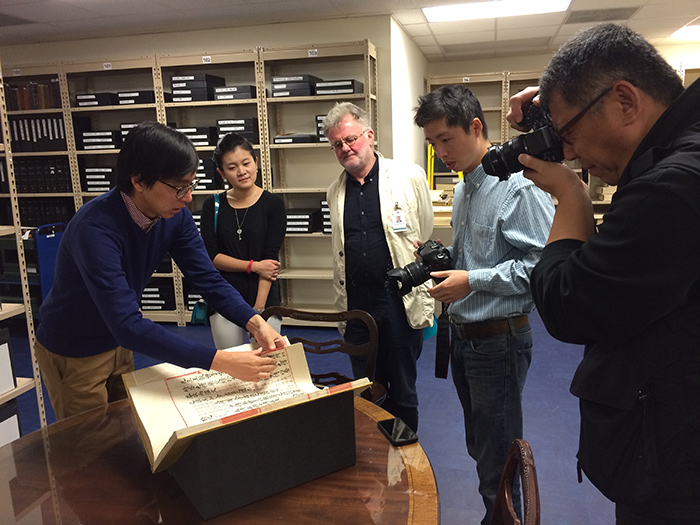

Huntington archivist Li Wei Yang (left) and Duncan Campbell show the new discovery to a group of journalists.

Even by the standards of the day, the task the 15th-century Yongle emperor in China gave to his scholars was unreasonable: compile and organize a book containing all the knowledge of the world, and make sure the information was easy to access. Remarkably, they succeeded in the mission, producing the Yongle Encyclopedia (1408), a compendium of writings from ancient times through the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644). At the time, it was the largest book ever produced in China—or anywhere else—consisting of more than 11,000 volumes.

The Huntington recently discovered that it owns a single, bound volume of the massive work, comprising sections 10,270 and 10,271. It is from a 1562 handwritten copy of the original, commissioned by the Yongle emperor of the Ming Dynasty in 1403. The Yongle Encyclopedia (in Chinese, Yongle dadian, a title perhaps better translated as “compendium” rather than “encyclopedia”) assembled Chinese writings from a wide range of fields, including art, astronomy, Buddhism, geography, medicine, drama, and technology. It included text from 5,500 titles involving the collaboration of more than 2,000 scholars. They assembled the information into 22,877 sections, bound into 11,095 volumes, 10 to a box. Our volume had been unidentified since it came here in 1968, a donation from the daughter of a missionary to China, Joseph Whiting. Last August, project archivist Li Wei Yang examined the manuscript and tentatively identified it as part of the renowned encyclopedia, a hunch he later confirmed with the scholar Liu Bo of the National Library of China.

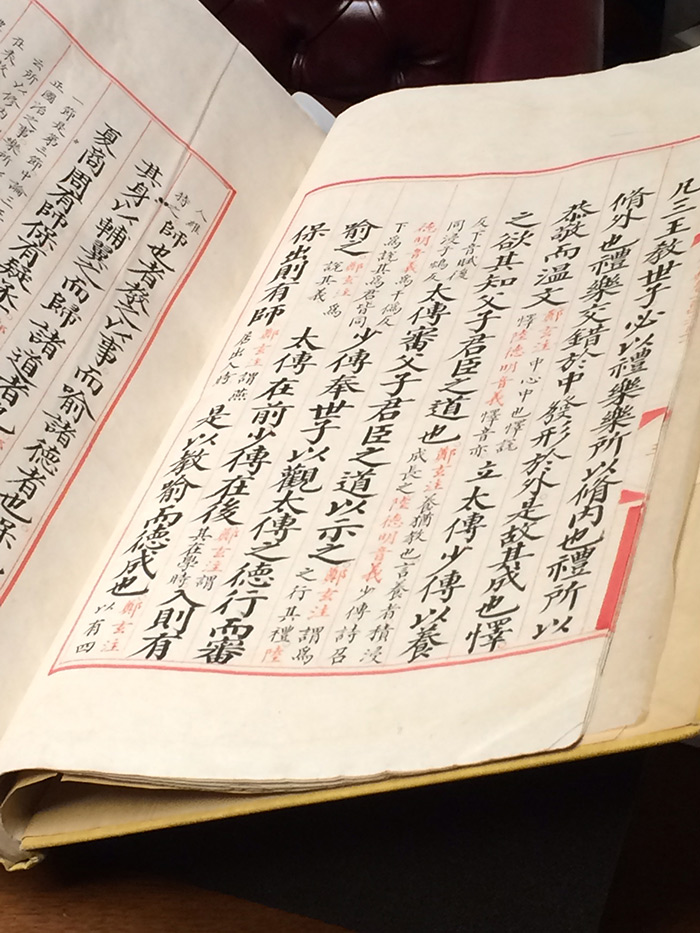

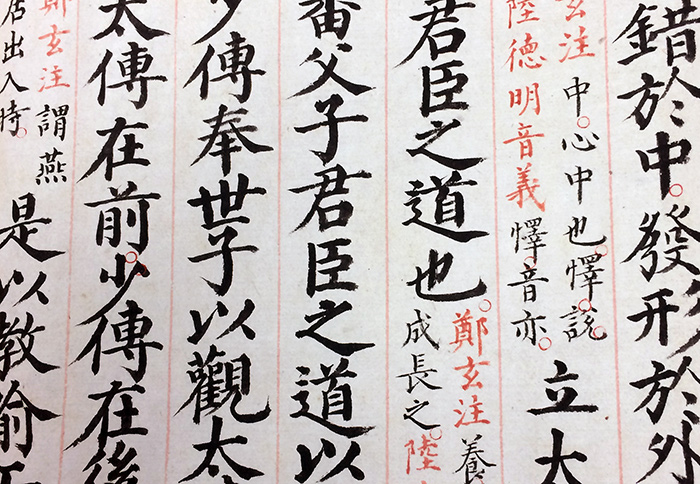

The Huntington’s volume contains a section from the Confucian Book of Rites explaining how to properly educate a prince. Missionary Joseph Whiting included a handwritten note translating part of this page. It read: “Rites and Music are the essentials in teaching the Heir Apparent. Music to cultivate the inner man, rites (or rules of propriety) to polish the external conduct."

To modern readers, one of the most fascinating elements about this work is the method used to organize such a gargantuan quantity of text—the rhyming categories of the Chinese language. In a classical Chinese world, arranging the book in this manner made perfect sense.

Chinese is not alphabetic. The order of the entries followed a rhyming dictionary, the Hongwu zhengyun, authorized by the Yongle emperor’s father in 1375. The dictionary divided the monosyllabic sounds of the Chinese characters into 76 rhyming categories, distributed among the four tones of the spoken language. Every educated Chinese person knew the categories and their sequence by heart. Rhyme was an exceptionally effective search engine.

For instance, our volume contains the partial text of a chapter from the Book of Rites ( Li ji), one of five books constituting the revered Confucian Canon. This particular section, entitled “King Wen as Son and Heir” (Wen wang shizi), deals with how to educate a prince who was both son to the ruling emperor and heir apparent. This created complications in terms of etiquette and ritual because the son, by virtue of his relationship with his father, would also become the Son of Heaven. The last character of the title means “son” and is pronounced “zi.” Anyone looking for information on the topic of “son” would immediately go to the second of the rhyming categories in the rising tone, under the category headword meaning “paper,” pronounced “zhi,” a sound with which it rhymed. The logic of this arrangement was crystal clear to Chinese thinkers in a traditional world. In their circles, the ability to write a good poem and effective prose was vital, and rhyme was critical to both.

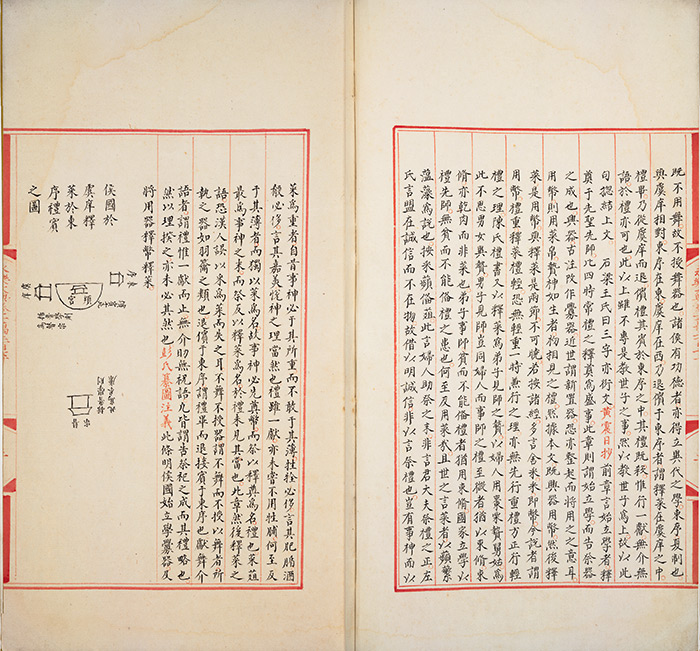

The diagram on this page, the only one in The Huntington’s volume, is meant to illustrate to the prince the appropriate ceremony used when establishing a school.

Though the title of the reign of the Yongle emperor (1360–1424; reign from 1402–24) who ordered the work meant Perpetual Joy, he proved a particularly brutal emperor in an already brutal age. His interest in the encyclopedia, however, was clear in the preface he wrote for it, in which he expressed a certain pride for how clearly it was organized. Consider my English translation:

The product of the labor of this exhaustive process of compilation is a book that can satisfy all possible inquiries, such that searching for a word by means of its rhyme and examining affairs by means of this word, any reader can trace the trajectory of something from beginning to end, as easily as shooting a swan with one’s bow. Nothing will remain hidden once you open up the pages of this book.

The encyclopedia was never printed. Luckily, a handwritten copy was produced in 1562, from which The Huntington’s volume originates. By the end of the Ming dynasty, the original copy had been lost. About 400 volumes remain of the 16th century copy, the majority of which are held in the National Library of China.

Wondering just how easy it might be to “shoot a swan with one’s bow”? Or simply curious to learn more about this recently discovered treasure? Come take a look at several pages from our volume, on view until March 16, 2015, in the East Foyer of the Library Main Hall. You can also view it through the Huntington Digital Library. And tonight, Jan. 8, I will be joined by Li Wei Yang, who was recently named curator for Western history, to give a joint lecture titled “The Yongle Dadian: An Emperor's Encyclopedia.” The free event will be held at 7:30 p.m. in the Ahmanson Room of the Brody Botanical Center. No reservations required.

Duncan Campbell is The Huntington’s June and Simon K.C. Li Director of the Center for East Asian Garden Studies and Curator of the Chinese Garden.