Posted on Thu., March 31, 2011 by

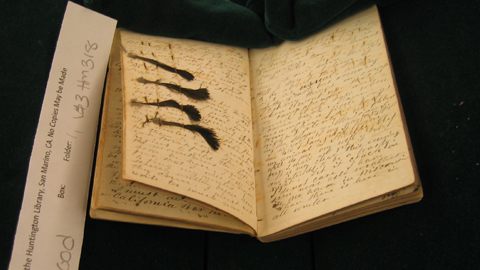

Feathers from a blue quail have been pressed in the diary of Joseph Wood, who traveled overland to California in 1849.

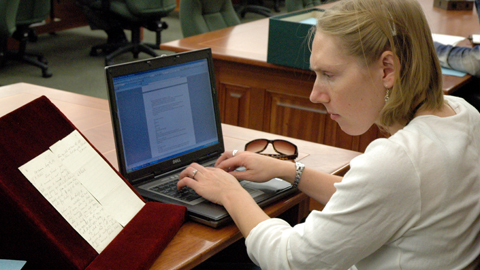

William Deverell, the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW), chats with USC doctoral student Sarah Keyes about her research on the Overland Trail experience of 250,000 Americans who moved west before the Civil War. This is the first in a new series highlighting the work of USC graduate students.

WD: When did you become interested in history?

SK: When I was a kid I enjoyed reading fiction, especially historical fiction. My family and I also did a lot of traveling, including many sites in the American West. When I was eight we visited Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. I think I initially wanted to be an archaeologist, but reading was more up my alley than fieldwork.

WD: And why the history of the American West?

SK: I think that my initial interest in Native American history drew me toward the West, but I think that being a ninth-generation Californian and growing up in a community composed of mostly recent East Coast transplants made me think a lot about being a Californian and a westerner.

WD: What's your dissertation about?

SK: It's about the place of the Overland Trail in American culture. I read overland narratives both for what they reveal about the actual journeys and their relationships to broader themes of 19th-century American history. I'm exploring themes such as western expansion and manifest destiny, slavery and freedom, and the culture of death.

WD: What do we already know about this topic?

SK: We know about the routes overlanders traveled and that they exaggerated their violent encounters with Indians. Historians have written about the difficulties of the journey and the ways travelers tried to maintain the gender conventions of their home communities.

WD: What don't we know that you are going to tell us?

SK: For 30 years no scholar has taken the Overland Trail seriously. I hope to provide a new understanding of the trail experience, westward expansion, and American identity.

WD: Where do you do your research?

SK: I spent a year at The Huntington Library reading overland accounts. For the past six months I've been traveling to different archives around the country, including the American Antiquarian Society, Newberry Library, Beinecke Library at Yale, and the New York Public Library. These sources are everywhere.

WD: What have you found that reminds us how strange and curious the past can be?

SK: There are many, many instances. It's hard to pick one. But I think the most curious is the story of William Keil, who brought the corpse of his dead son from Missouri to Oregon. The elder Keil was the founder of a religious sect and had promised his son that he could ride at the head of the train. He kept his promise. His son lay in whisky in a lead-lined coffin at the head of the wagon train all the way across the plains, the Rockies, and the Great Basin. They buried the boy after they arrived in Oregon.

Sarah Keyes is the 2008 recipient of the Louis Pelzer Memorial Award from the Organization of American Historians, which recognizes the best graduate student essay in American history. Her dissertation, "Beyond the Plains: Migration to the Pacific and the Reconfiguration of America, 1820–1900," will be completed in spring 2012.

William Deverell is the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW).