The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Power of Touch

Posted on Mon., April 10, 2017 by

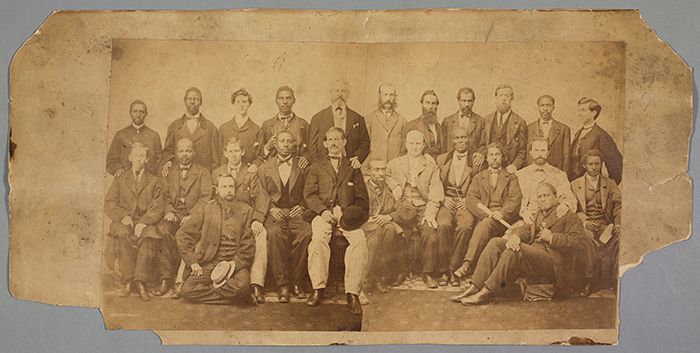

The 24 members of the petit jury impaneled by the United States Circuit Court for Virginia in Richmond for the treason trial of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis in May 1867. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Click here to enlarge.

The 24 members of the petit jury impaneled by the United States Circuit Court for Virginia in Richmond for the treason trial of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis in May 1867. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Click here to enlarge.One afternoon in the Library’s archive, I found a battered and scuffed photograph at the bottom of a small pile. Twenty-four men gaze somberly at the camera; all wear jackets and ties. The mere fact that the 19th-century portrait showed Black and white men respectfully intermingled made the photograph compelling enough. But there was something about the gesture of their hands that stopped me in my tracks. I had the sense that the picture was important. I just didn’t know precisely why.

The photograph revealed few facts. A composite of two images crudely pasted together (the obvious overlap between the man in checked pants at center and the sitter next to him provides a clue), it had no date or other identifying information. On the picture’s back, a studio stamp: the Lee Photographic Gallery.

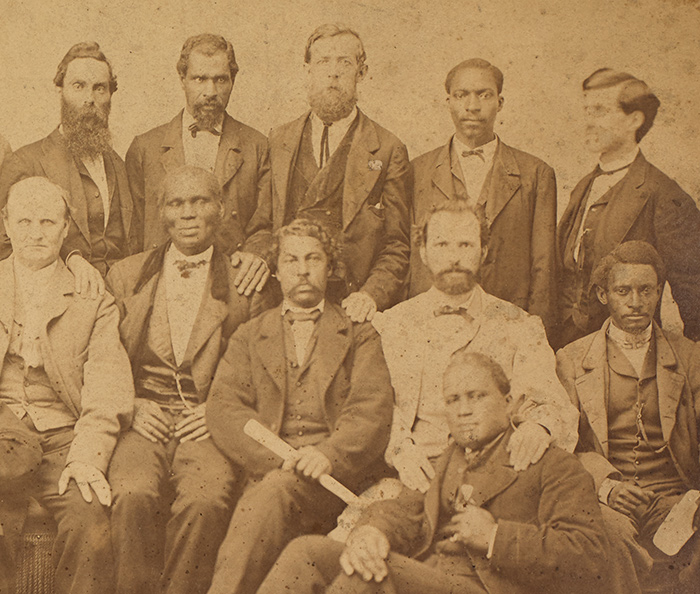

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.I asked Anita Weaver, the curatorial department’s research assistant extraordinaire, to track down any information she could find. Within a day, she came back with the hoped-for news. The photograph was a significant find: a rare surviving original picture of the first racially integrated petit jury (another name for a trial jury) in Virginia history.

There was more. The historic jury of 12 African American and 12 Anglo American jurists was selected in the spring of 1867 for the trial of none other than Jefferson Davis. The former president of the Confederate States of America had been charged by the federal government with treason.

This was one bit of American history that I’d never learned. As the Confederacy crumbled in April 1865, Davis fled the executive mansion in Richmond and headed south toward Texas. Union cavalrymen apprehended him a month later in Georgia and sent him to Fort Monroe, Virginia, a military installation where he was imprisoned while awaiting trial for the next two years.

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: L. Boyd, Thomas Lucas, L. Lipscomb, A. Lilly, and (unknown first name) Wilburn. Seated: B. Wardwell, Albert Royal Brooks, Lewis Lindsey, J. Morrisey, J. Turner (in foreground), Dr. W. Scott. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: L. Boyd, Thomas Lucas, L. Lipscomb, A. Lilly, and (unknown first name) Wilburn. Seated: B. Wardwell, Albert Royal Brooks, Lewis Lindsey, J. Morrisey, J. Turner (in foreground), Dr. W. Scott. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.The Virginia jurists were chosen by United States Circuit Court judge John C. Underwood, a Radical Reconstruction firebrand whose speeches about the “moral monsters” of racism put him at odds with moderates on both sides of the political divide.

All this research raised more questions than answers. How did Judge Underwood choose these men? And who were they? A few identities came into focus. Lewis Lindsay (seated and holding a scroll in the image above) was a fearless advocate for the confiscation of Confederate lands. Born enslaved in Virginia, Lindsay worked at a Richmond iron works after the war. Albert Royal Brooks (seated second from left in the image above) purchased his and his family’s freedom between 1861 and 1865, and became a respected Richmond businessman and community leader. Joseph Cox (standing far left in the image below) was a free Black man employed as a factory worker, blacksmith, bartender, and storeowner during his lifetime.

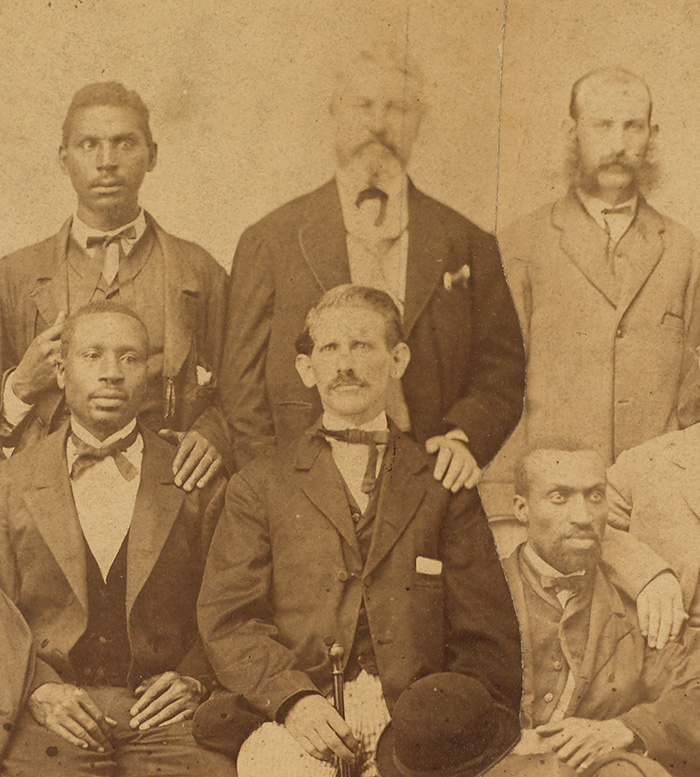

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: Joseph Cox, Herman L. Wigand, L. Tabb. Seated: F. Smith, J.E. Frazier, J.B. Willis. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: Joseph Cox, Herman L. Wigand, L. Tabb. Seated: F. Smith, J.E. Frazier, J.B. Willis. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.Who were the white jurors? Jefferson Davis’s friend, lawyer James Lyons, referred contemptuously to them as “the worst kind of white men.” Like Lyons, members of Richmond’s ruling class deplored the case against Davis, considering a mixed-race jury a bitter affront.

The circumstances surrounding the creation of the photograph also remain unclear. A Richmond photographer, David H. Anderson, most likely performed the job. He split the group into two, probably because his large-format camera could not accommodate 24 sitters in a single frame. At some point, a neighboring studio owner, William W. Davies of the Lee Photographic Gallery, obtained the two glass negatives and began to print and sell the portrait, as demonstrated by the stamp affixed to the back. Sales were sparse; only a handful of copies exist. How and when this remarkable photograph came to The Huntington is yet another mystery to be solved.

I kept coming back to the hands. The group is linked together by that most human of gestures, touch. Even still, that contact is racially bound. Black touches Black. White touches white. White touches Black. But only in one case does an African American man, E. Fox (standing far left in the image below) place a hand on a white man’s shoulder—and then, in a most tentative way. This cautious touch seems a telling symbol of what was to come.

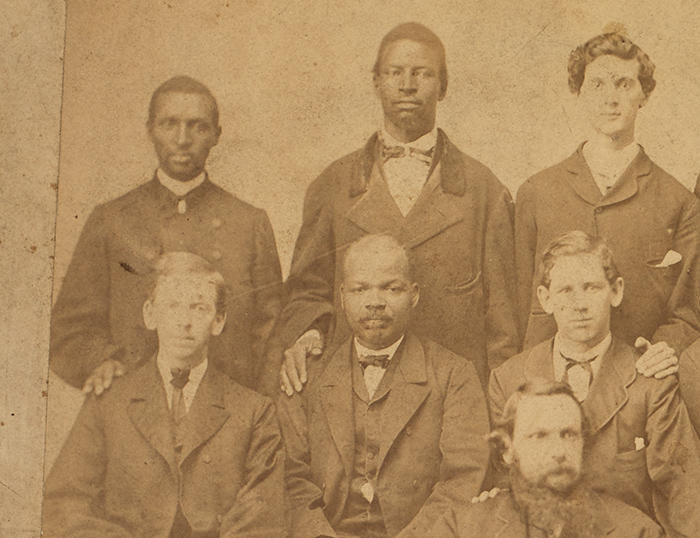

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: E. Fox, J. Freeman, J.R. Fitchett. Seated: W.A. Parsons, L. Carter, C.P. Fitchett, John Newton Van Lew (in foreground). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Garden.

Detail of a group portrait of the petit jury impaneled for the Jefferson Davis treason trial, 1867. Left to right, standing: E. Fox, J. Freeman, J.R. Fitchett. Seated: W.A. Parsons, L. Carter, C.P. Fitchett, John Newton Van Lew (in foreground). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Garden.The petit jury heard cases during its term, but not the most famous one for which it had been impaneled. On May 13, 1867, amid jubilant shouts, Jefferson Davis walked out of the courtroom on $100,000 bail. A group comprised of northern industrialists and radical abolitionists had paid $10,000 each toward Davis’s bond, an action emblematic of the haste with which many wished to heal the wounds of war.

The government formally dismissed charges against Davis in early 1869, despite his emphatic desire to plead his case. The will to prosecute simply faded over time. Jefferson Davis—an unrepentant champion of slavery and the Confederacy’s “Lost Cause”—never went to trial.

Jenny Watts is curator of photography and visual culture at The Huntington.