The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Preserving Parks for People

Posted on Wed., Dec. 14, 2016 by

William R. Leigh, Grand Canyon (1911), as adapted for Fred Harvey Service dining car menu, 1950. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Used with permission of the BNSF Railway Company.

“Geographies of Wonder: Evolution of the National Park Idea, 1933–2016,” an exhibition in the Library’s West Hall, examines how the idea of national parks evolved over time.

Two images at the entrance bookend the history of the park system, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. One is a full-color rendering of the Grand Canyon. Back in the late 19th century, awe-inspiring images like these made the case for preserving America’s scenic landscapes. The other image is a recent map of the proposed “Rim of the Valley” expansion of Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, a modern-day effort to preserve some of the last wild lands and historic sites in the greater Los Angeles area.

The exhibition’s nearly 100 items include maps, advertisements, illustrated guide books, travel narratives, promotional brochures, scientific surveys, reports, and correspondence. Taken together, they illustrate the paradox the National Park Service faces—how to make the lands under its management available for public enjoyment while preserving them for future generations.

People have streamed to the parks, since their inception, in ever-growing numbers. (An exception was the period during World War II, when the rationing of gasoline and rubber curtailed recreational travel and the parks were shut down.) In 2015, more than 300 million people visited the parks.

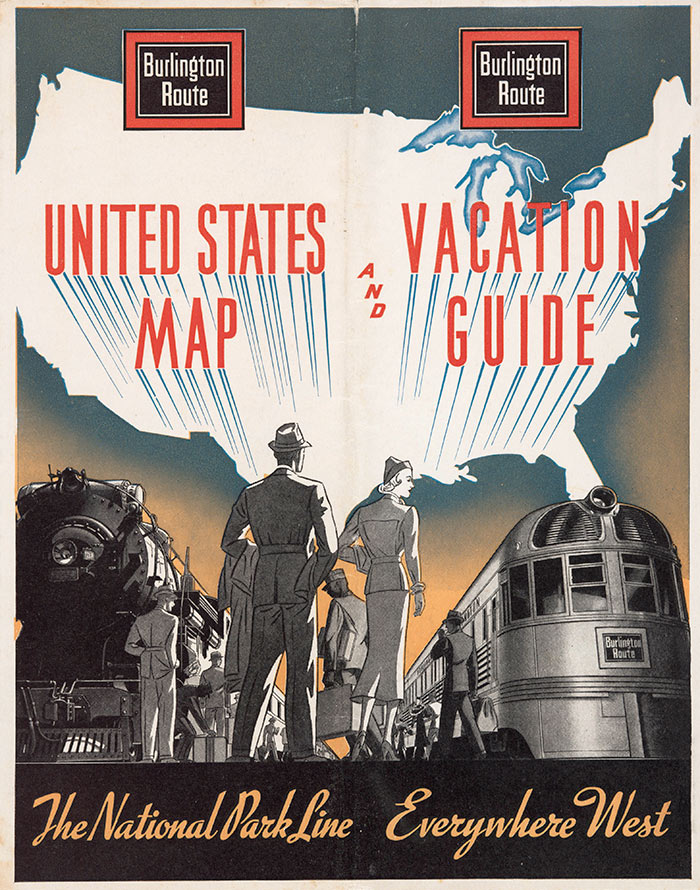

Burlington Route, United States Map and Vacation Guide, cover, 1938. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Railroad companies fostered national park tourism with enticements such as the Burlington Route’s “The National Park Line—Everywhere West.” Enthusiasm for travel by personal automobile was extolled in such advertisements as “Trails and Automobile Drives” in the Grand Canyon. The advent of air travel presented a pivot point, according to exhibition curator Peter Blodgett, H. Russell Smith Foundation Curator of Western Historical Manuscripts.

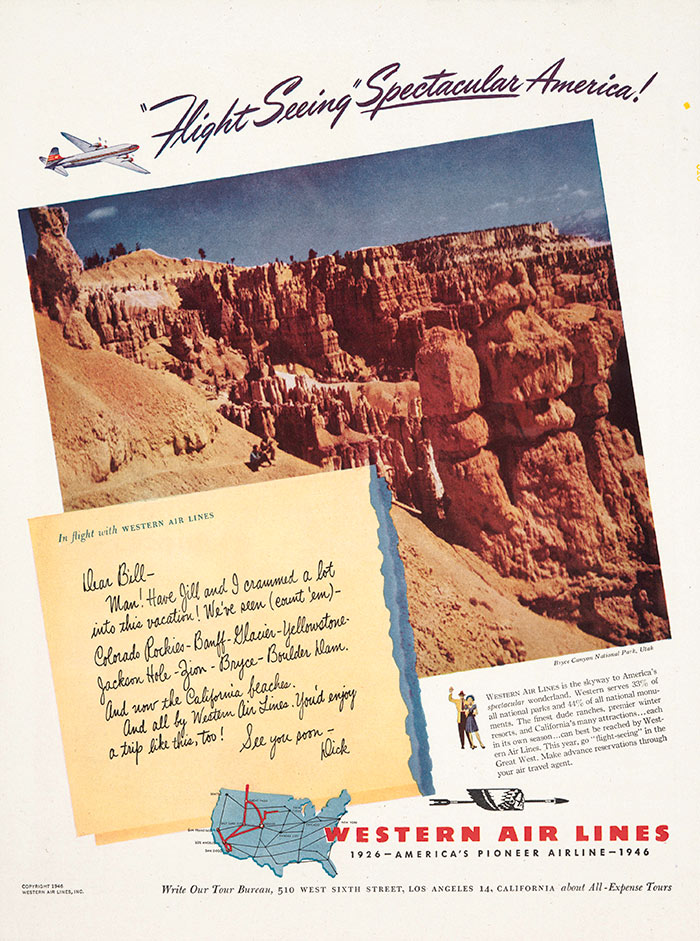

The headline from a 1936 United Airlines advertisement promises “14 Days in Yellowstone on a 2-Week Vacation!” A Western Airlines advertisement 10 years later ups the ante with a full-color photo of Bryce Canyon’s tall, slender rock spires, the so-called “hoodoo formations,” that neatly linked the breathtaking panorama with plane travel.

Observes Blodgett: “Americans wanting to immerse themselves in the wild relied on the epitome of transportation technology in that moment.”

Western Air Lines, “’Flight Seeing’ Spectacular America,” advertisement, 1946. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

By the 1940s and 1950s, post-war prosperity brought hordes of vacationers that tipped the scales—putting extreme pressure on aging park facilities and threatening wildlife habitats. In the March 1949 issue of Harper’s Monthly, historian and conservationist Bernard DeVoto warned of the federal government’s failure to adequately fund the National Park Service: “the situation is shocking and it is becoming critical.”

Notre Dame University senior Robert Browne used his time as a Huntington intern this past summer to flesh out parts of the exhibition materials, including those related to the growing ecological movement. He examined the 1968 book Desert Solitaire by radical environmentalist Edward Abbey, who complained about automobile access to these protected landscapes. Abbey scorned the “indolent millions born on wheels and suckled by gasoline” who demanded that the parks accommodate their “industrial tourism.” Abbey’s words impressed Browne with their forcefulness. He also noted that the writer still seemed “at peace with himself because of how connected he was with the natural world.”

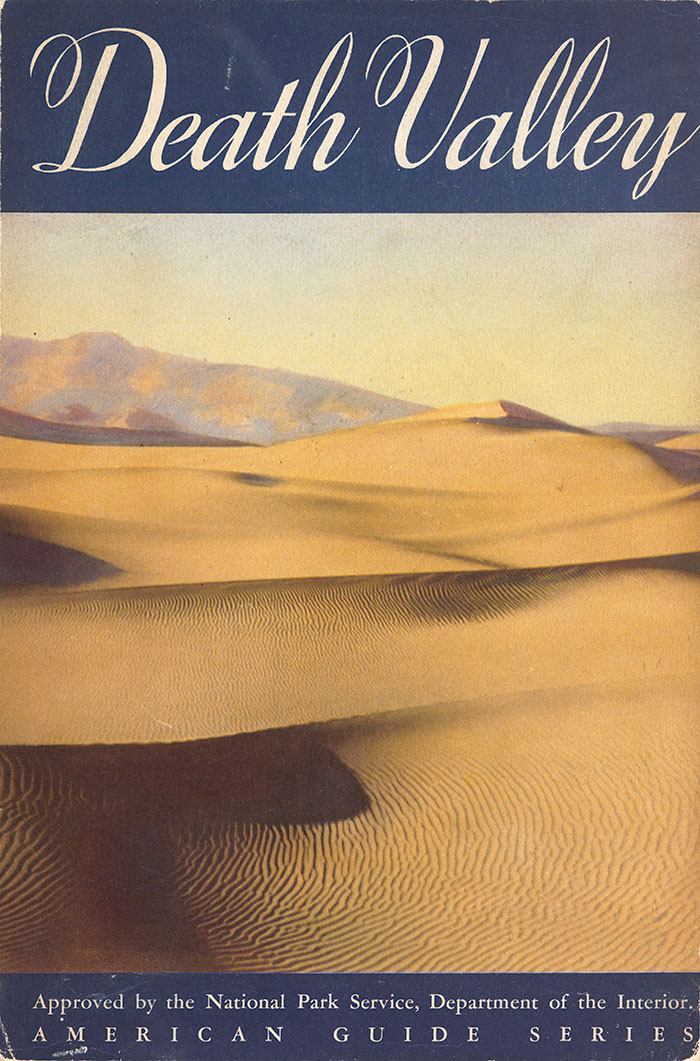

The very definition of national parks evolved over time. By the 1930s, locations once considered desolate and forbidding, such as California’s Death Valley and Joshua Tree, became national monuments. In the 1960s, the Park Service began protecting seashores, lakeshores, wild and scenic rivers, and historic trails.

Federal Writer’s Project, Death Valley: A Guide, cover, 1939. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The 1970s and 1980s brought the creation of national recreation areas adjacent to major urban areas, such as the Gateway National Recreation Area in New York City and San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. President Barack Obama may one day be remembered as the president who protected more public lands and waters than any previous president—265 million acres at last count.

In Blodgett’s view, these protections should not be taken for granted. Parks have remained a subject of contention throughout American life: “Like the protection of liberty, the protection of park spaces requires eternal vigilance,” he says.

What’s your view? Comment books in the entry hall are available for visitors to register their thoughts. Do you think it’s important to preserve parks for people?

“Geographies of Wonder: Evolution of the National Park Idea, 1933–2016” is on view in the Library’s West Hall through Feb. 13, 2017. The first part of this two part-exhibition, “Geographies of Wonder: Origin Stories of America’s National Parks, 1872–1933,” ran from May 14–Sept. 5, 2016.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing.