The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Radiant Beauty

Posted on Wed., April 25, 2018 by

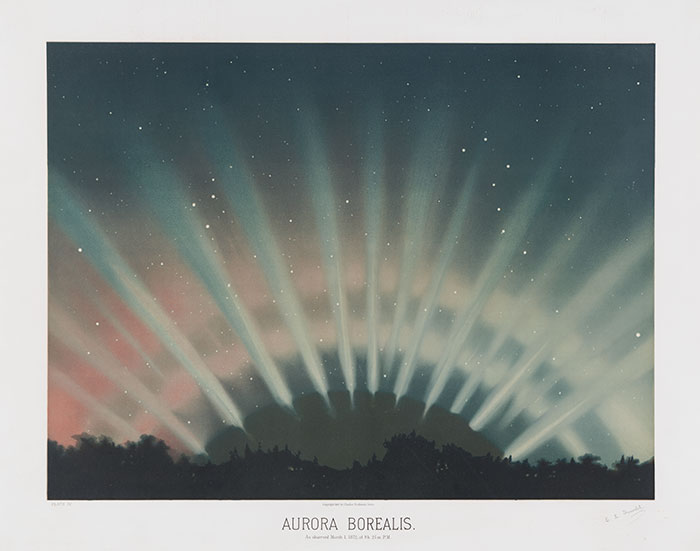

E. L. Trouvelot (1827–1895), Aurora Borealis, 1881, color lithograph, 25 3/4 × 32 3/4 in. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

E.L. Trouvelot made one big mistake in his life: releasing, by accident, moths he was studying into the woods near his home in Medford, Massachusetts in the 1860s. This error, which had dire consequences for North America’s hardwood trees, has obscured Trouvelot’s very real achievements in art and astronomy. “Radiant Beauty: E.L. Trouvelot’s Astronomical Drawings,” opening April 28 in the Library’s West Hall, represents the zenith of his career: the 15 chromolithographs published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1882.

“Kudos to Trouvelot,” says Krystle Satrum, assistant curator of The Huntington’s Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. “He moved on. He said, ‘Maybe my role is not to be a great entomologist. I’ll use my artistic skills and move to another field.’”

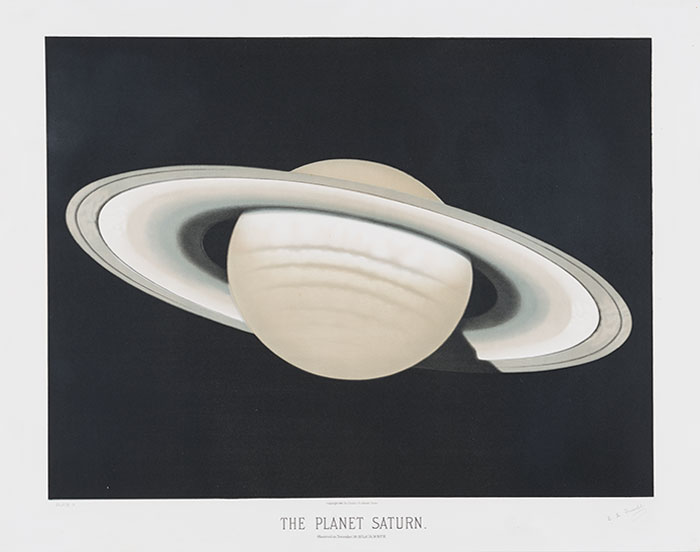

E. L. Trouvelot (1827–1895), The Planet Saturn, 1881, color lithograph, 25 3/4 × 32 3/4 in. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

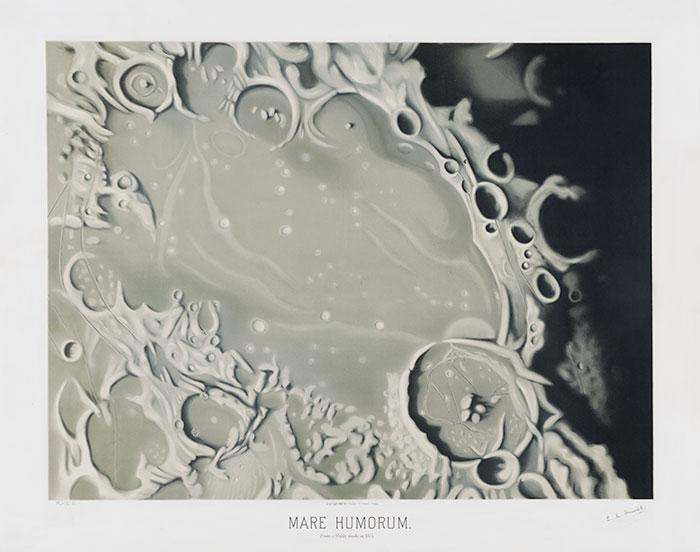

Born in France, Étienne Léopold Trouvelot (1827–1895), a self-taught astronomer, produced more than 7,000 astronomical illustrations and 50 scientific articles in his working life. His depictions of planets, comets, eclipses, moon craters, and sunspots display the wonders of the cosmos in vivid color and meticulous detail.

“He had an uncanny capacity to combine art and science in such a way as to make substantial contributions to both fields,” observes Satrum.

Trouvelot’s singular mix of talents garnered him a position in 1872 at the Harvard College Observatory. In 1875, the U.S. Naval Observatory invited him to use their 26-inch refracting telescope, then the world’s largest. And, in 1876, Harvard published a volume containing 35 lithographs based on his drawings of solar phenomena.

Astronomy enjoyed the status of a popular science in the latter half of the 19th century. “You could get your own telescope, start looking at the stars, and learn as you go,” says Satrum.

E. L. Trouvelot (1827–1895), Mare Humorum, 1881, color lithograph, 25 3/4 × 32 3/4 in. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Trouvelot showed several of his pastels at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where the general public could view them. That exposure led Scribner’s to publish some 300 sets of the 15 chromolithographs on view in the “Radiant Beauty” exhibition.

Each set included Trouvelot’s manual, also on display in the West Hall, with specific descriptions of his observations and each plate. The content reflects what was known at the time about such celestial bodies as the Moon, Mars, and Saturn.

Full sets of the color lithographs are rare today. As early 20th-century advances in photographic technology permitted more accurate and detailed depictions of astronomical phenomena, the libraries and observatories that owned the portfolios discarded the prints or sold them to collectors. Jay T. Last donated his set to The Huntington as part of his collection of graphic arts and social history. “Radiant Beauty” marks the set's first public exhibition at The Huntington.

E. L. Trouvelot (1827–1895), The Great Comet of 1881, 1881, color lithograph, 32 3/4 × 25 3/4 in. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As dazzling as these lithographs look in this blog post, seeing them in person has an “indescribable effect,” says Satrum. “You’re viewing a 135-year-old, beautiful pristine print. There’s still that ‘wow’ factor that you get when you’re looking at the originals.”

Trouvelot wrote, “No human skill can reproduce upon paper the majestic beauty and radiance of the celestial objects.” His own works seek to disprove those words.

You can watch a video about the exhibition—with commentary by Krystle Satrum, assistant curator of The Huntington’s Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History—on YouTube.

To place Trouvelot’s contributions in context, visit the astronomy section of “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World,” located next door to the “Radiant Beauty” exhibition. You can see how Galileo, Newton, and other pioneers of astronomy observed the heavens and recorded their experiences.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.