The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Railroad Confidential

Posted on Wed., May 31, 2017 by

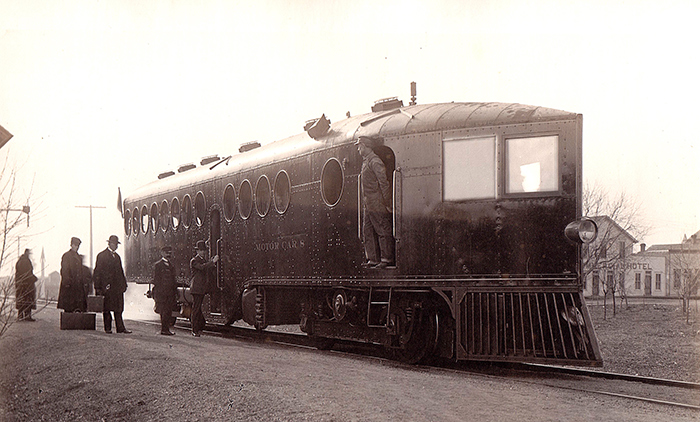

McKeen Motor Car, 1906. The sleek McKeen motor car, a gasoline-powered railway vehicle with innovative porthole windows and an aerodynamic “wind-splitter” front end, was the brainchild of engineer William R. McKeen Jr. (1869–1946). Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Patent papers. Drawings of railcars. Engineering notes. Photographs of trains and machine shops. These were the kinds of materials I expected to encounter as I began organizing the personal papers of William Riley McKeen Jr. (1869–1946), a mechanical engineer and innovator who developed some of the first gasoline-powered railroad cars in the U.S.

But an entirely different world emerged when I opened a weathered brown envelope scrawled with “Lawsuit and settlement, 1913.” Brothels. Gentlemen’s clubs. Private detectives. Prostitutes.

It turned out that, in 1912, while overseeing the design and manufacture of the stylish “McKeen Motor Car,” McKeen became embroiled in a court battle in Omaha, Nebraska, brought by his new wife’s ex-husband, Charles W. Hull.

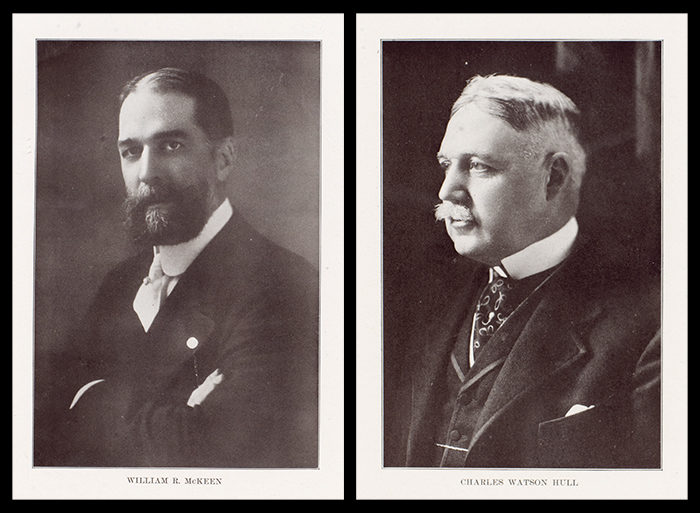

William R. McKeen Jr. (left) and Charles W. Hull, from Omaha: The Gate City, and Douglas County, Nebraska / A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement, Arthur C. Wakeley, ed., (Chicago: S. J. Clarke, 1917). Unidentified photographers. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Hull, one of Omaha’s leading businessmen, filed suit to avoid paying $91,000 in alimony to his former wife, who had become Mrs. Mary McKeen. The couple fought back. They hired a private detective, intending to prove that Hull was little more than a drunken philanderer and loyal patron of the city’s most notorious houses of “ill fame.” The detective struck gold.

As I dug through the contents of the envelope, I read how Detective H. J. Pickett interviewed 200 witnesses over the course of eight months. He discovered that Hull and a large coterie of Omaha’s business elite were habitués of the city’s “sporting district” underworld. The detective’s 41-page transcript of interviews with prostitutes, brothel owners, barmaids, and other employees of Omaha’s social clubs resulted in a report rich in social and cultural detail. There were eyewitness accounts of sexual escapades, raunchy behavior at poker games, public drunkenness, and backdoor assignations, all of which identified the full names of both the witnesses and the prominent society members involved.

“A Good Pair to Hold,” advertising card, ca. 1890. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In sometimes graphic language, the report revealed the underbelly of Omaha’s high society and how it operated. Titillating and damning details aside, the document also uncovered telling details regarding societal norms, race, gender, and class.

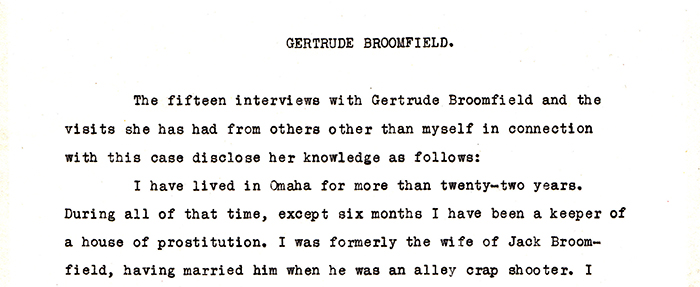

For instance, the account by brothel owner Gertrude Broomfield tells a little of her life history: “I have lived in Omaha for more than 22 years. During all that time, except six months I have been a keeper of a house of prostitution . . . and had as my patrons some of the best men in Omaha . . . .” She went on to explain how visiting brothels was often a family affair, as she counted among her clients “the young Hamilton boys, the Krug boys, the Metz boys, the Kountz boys . . . and hundreds of women and men you would little suspect of visiting that district.”

Nellie Jacks, whom the detective reported “was located for me by Tom Vann, a notorious vamp about town,” began her statement plainly: “For nine years I was night door maid at Minnie Fairchild’s house of prostitution, 120 South 9th Street.”

Excerpt from Detective H. J. Pickett’s 41-page transcript of interviews with prostitutes, brothel owners, barmaids, and other employees of Omaha’s social clubs. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Bradley Walker, a waiter at the Omaha Country Club and the Rome Hotel, explained: “I do not want to have anything to do with this case, because the waiter who does will be blacklisted for life . . . no colored person can give evidence in this case on either side and remain in Omaha at any of the ordinary occupations.”

One witness offered his insights into human nature and class. Lee Travis, who was employed in the hotels and clubs in Omaha for 20 years and knew Mr. Hull well, said this: “You know how rich men take liberties with women along moral lines. [Hull] was fly with women, especially when he was in his cups. I have seen him do many immoral things.” The detective noted Travis’s reticence to testify because “he wanted to get back to work and feared that Hull could prevent it.”

As evidence mounted against him, Hull dropped the suit, and the case never went to court.

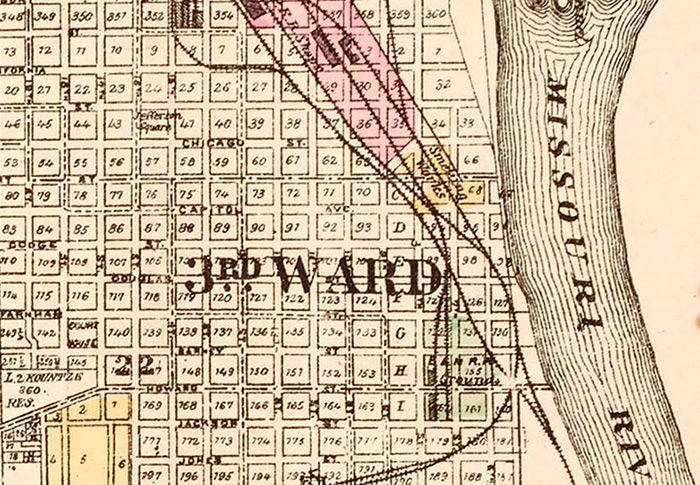

Detail of map of Omaha, Nebraska, 1887. This detail shows the vicinity of some of the brothels downtown by the railroad tracks and the river: “House of all Nations” at 9th and Dodge Street. (on map at the top of the second “R” in “3rd WARD”); “Mongrel House” at South 16th Street; and “Minnie Fairchild’s” at 120 South 9th St. (on 9th, just below Dodge Street). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When all was said and done, Detective Pickett described how this unsavory, bribery-filled undertaking required patience, intelligence, and nerves of steel—but what motivated him? He wanted the report to serve a larger social purpose, and at several places in the document, he takes on a personal, cautionary note. His hope, he said, was that the report would provide a “permanent source of information” to “. . . help others avoid the fate [of prostitution].”

Did McKeen forget the salacious report was part of the railroad materials he handed over for posterity? We’ll probably never know, but The Huntington now has a fascinating slice of social history for scholars to study.

Suzanne Oatey is a project archivist in the Library’s curatorial department, where she is currently organizing a collection of railroad materials from the estate of Donald Duke.