The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Raven Named Sir Nevermore?

Posted on Mon., Oct. 31, 2016 by

Embossed, color lithographed inner lid label of a cigar box, no date, from the Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I remember the moment when I fell in love with the Huntington Library. I was researching 19th-century agriculture and, in particular, the use of guano—the droppings of cormorants, boobies, and pelicans on the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru.

Hard as it is to believe now, this was the hot commodity in the 19th century. Renowned for its fertilizing powers, it was called “white gold.” The United States nearly got into a war with Peru over it, and the “guano question” was discussed in three annual messages by U.S. presidents. I wondered what The Huntington had on the stuff.

Quite a lot, as it turned out. There were agricultural treatises, manuals, advertisements, and sheet music related to guano. And then there was an intriguing catalog entry for the papers of a certain “Sir Manson Nevermore, RPA, 1848–2005.” I clicked the link.

I should say now that, in my career, I’ve seen a lot of catalog entries. But I’d never seen an entry like this.

Sir Manson, I learned, was “a venerable, although somewhat deranged and unkempt raven that was irritating the hell out of the Manuscripts Department of the Huntington Library in 2003 and 2004.” His papers, continues the catalog entry, were “an unwelcome gift” of Sir Manson himself and are “restricted to readers willing to climb up on the roof.” They contain, besides two pounds of bird droppings, “field notes compiled by Nevermore in the process of his activities, including treatises on window pecking, wing flailing, yodeling, pooping, and general avian vandalism.” Subject headings include “Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery – Fauna,” “Guano – Production and direction – California, Southern,” and “Human beings – Infuriation of, Avian.”

“The Huntington,” I thought. “This is my kind of place.”

I ordered the Nevermore papers in the Ahmanson Reading Room. I got some nervous giggles, but no archival boxes filled with bird droppings. So where did this entry come from? I showed it to Anne Blecksmith, the head of Reader Services. She was puzzled. “How did this get here?”

Anne poked around. The record had been edited 23 times, far more than the usual entry. But it was over 10 years old. Would I be able to find out who wrote it? “Maybe the curators know something,” Anne advised. “Birds are always banging the windows of their offices. In fact, I think Melissa Lo sent around a picture of one.”

The game was afoot. I knocked on Melissa’s door—she’s the Dibner Assistant Curator of Science and Technology. She welcomed me into her office, and I saw a high window over her desk. “Melissa,” I said, pointing to it, “Tell me about the birds.” “You mean Manson?” she asked. I don’t think real detective work actually ever goes this smoothly.

Title page of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, published by E.P. Dutton and Co., no date. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The person you want to talk to is Olga Tsapina,” said Melissa. Olga is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts and, I am now convinced, the hidden genius behind the whole thing.

I found her at her desk. “How do you know about Manson?” she asked. I explained my guano research. “Ah,” she said, and sat back in her chair. She knew this day would come.

The story tumbled out. It was 2004. The library was adopting a new interface and the curators wanted to create a catalog entry to test the system. But the curators were, by that point, under siege from a months-long raven onslaught. There was one “deranged raven,” Olga explained, who had been attacking their windows twice daily. At 9 a.m., “he would start prancing around the ledge,” cooing and gazing at his own reflection in the ultraviolet shielding on the windows. Then, his narcissism turning to rage, he would “fling himself at the windowpane” and furiously try to tear down the UV shielding. The whole show repeated at 4 p.m.

I looked at the windows. Large strips of the UV shielding were missing.

Countermeasures, Olga explained, were taken. The late Bill Frank—curator of Hispanic, cartographic, and western American manuscripts—got up on the roof, flapping his hands to try to scare Sir Manson off. Dan Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology and a noted expert on the history of ornithology, tried making hawk sounds. A Nerf ball was deployed, though with little result.

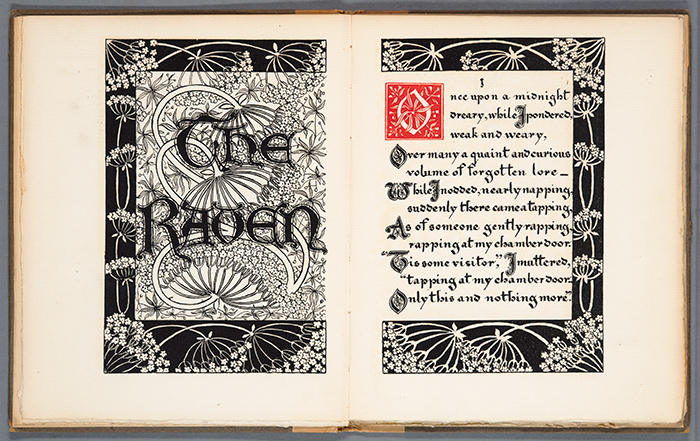

A.C. Smith’s portrait of Edgar Allan Poe, 1843 or 1844, watercolor on paper. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Confronted with a similarly insistent raven, Edgar Allan Poe had turned to poetry. The curatorial staff, instead, expressed its soul in the distinctive idiom of archivists: the card catalog entry.

The Sir Manson Nevermore entry, it should be said, is a model of the form, like a perfectly executed sonnet. Because the record was designed to test the system, it has values for all fields. Thus, our raven has a name (“Manson,” after the serial killer to whom the raven is said to bear a physical resemblance; “Nevermore” as a nod to Poe), a title (Sir), and even a post-nominal title (RPA: Royal Pain in the Ass).

The staff composed the entry, Olga at the keyboard, as a joke—“a collective effort born of cooperation and amidst multiple bouts of undignified giggling.” But Richard Jackson, supervising librarian, insisted that it remain. Jackson teaches cataloging, and he uses the entry in his classes. Budding archivists, in other words, cut their teeth on the Sir Manson record.

It has traveled further than that. Because The Huntington’s system connects to larger databases, Sir Manson Nevermore has been absorbed into the great global bibliographic network. He’s in WorldCat; he’s in ArchiveGrid. Researchers anywhere on the planet working on guano—my specialty—might stumble across the record. So might those working on “skylights and windowsills” or on “scratches and beak marks.”

And they have. I found Manson. So did the staff at the Library of Congress. Search the great libraries of the world for those holding “excrement samples,” and there you’ll find Sir Manson, tapping, tapping at the windowpane.

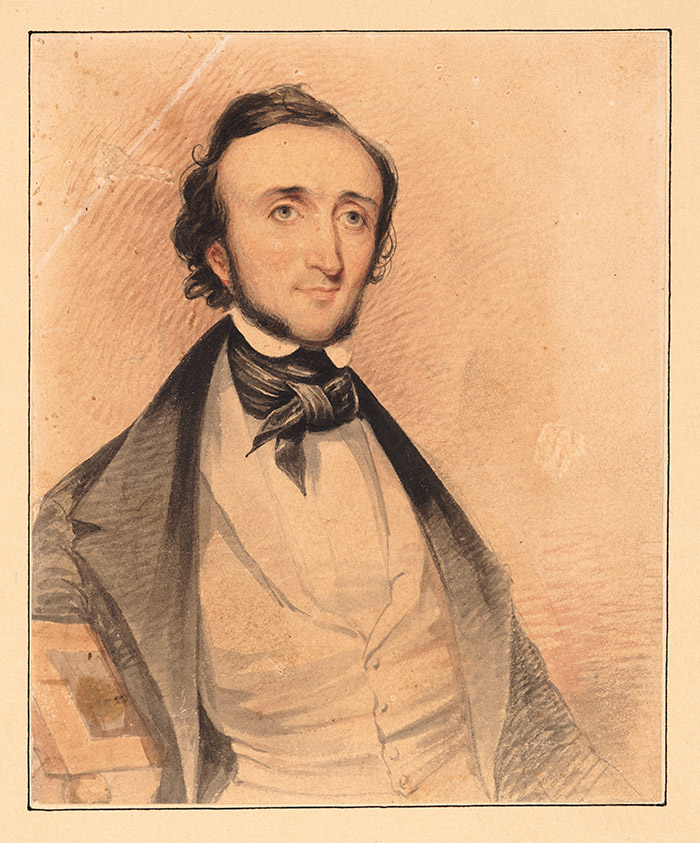

A bird that appears to fit Sir Nevermore’s description flails its wings against a Library window in 2015. Photo by Melissa Lo.

“Manson is one of my proudest achievements,” Olga beamed.

The catalog lists Sir Manson’s date of death as 2005. “The Manuscripts Department has refused to comment on Sir Manson’s sudden disappearance,” it says. But is Sir Manson dead?

Olga herself is uncharacteristically vague on the question. Sir Manson’s daily visitations ended in 2005. In that year, researchers found dead birds in 52 out of California’s 58 counties that tested positive for West Nile virus. So, that’s the official story.

Still, ravens can live for decades, and there have been some suspicious sightings. “He comes back every once a while,” Olga intimated in a conspiratorial tone. Indeed, Melissa’s photograph shows, if not Sir Manson, then certainly a bird who fits the description. “Deranged”? Check. “Unkempt”? Check. Flailing his wings while yodeling and pooping? Hard to tell from the photograph, but I couldn’t rule it out.

Olga floated another theory. The last time the curatorial staff definitively laid eyes on Sir Manson, there was another raven with him. Sir Manson did his usual demented hell-sprite routine while the other raven watched, looking vaguely horrified. The staff decided that Raven #2 was Sir Manson’s therapist.

Maybe he didn’t die, Olga suggested. “Maybe he got help.”

Daniel Immerwahr is assistant professor of history at Northwestern University and was a 2015–16 National Endowment for the Humanities fellow at the Huntington. He is the author of Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development. You can watch his lecture “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Guano But Were Afraid to Ask” on YouTube.