The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Robert Seymour, 19th-Century Political Cartoonist

Posted on Wed., Jan. 18, 2017 by

Robert Seymour, cover design for Volume One of The Looking Glass, 1830. Seymour depicts John Bull, the archetypal Englishman, turning his head to us and smiling gleefully at the rout of the Tory government by the jubilant Whigs (or Liberals). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington possesses a trove of images from the golden age of British caricature—most notably by artists Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and Isaac Cruikshank (1764–1811). It also owns some gems by Robert Seymour (1798–1836), an illustrator whose fame grew around the time of Rowlandson’s death. Today, Seymour is probably best known as the illustrator of the first two installments of Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers (1836), but in his own time, Seymour was a leading political cartoonist.

Seymour benefited from the rise of the caricature magazine, a new format publishers created to appeal to an expanding market of readers who wanted value for money. His best work was for Thomas McLean’s The Looking Glass (1830–36), the most successful and impressive of this new kind of visual satire. The Huntington owns a unique, complete, colored version of this magazine.

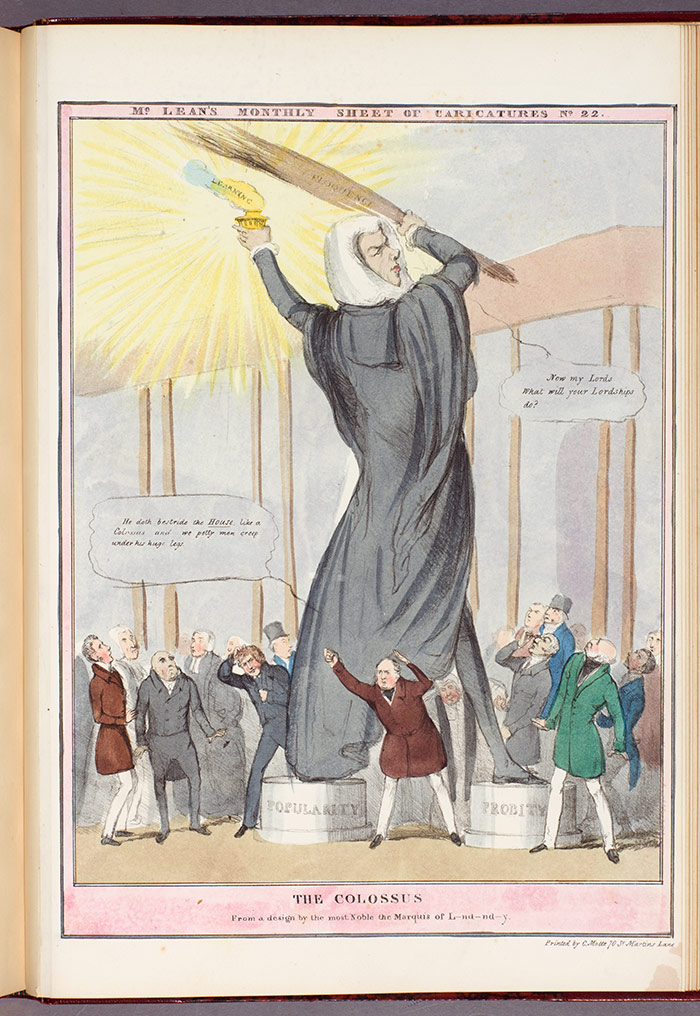

Robert Seymour, “The Colossus,” The Looking Glass, Oct. 1831. Seymour shows Lord Brougham (whose name sounded like "broom") as a colossus who is about to strike the Tories with his giant broom if they do not vote for reform. The scene is funny but also disturbing, as it implies that the new government could become tyrannical. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Looking Glass was published monthly and cost three shillings uncolored or six shillings hand-colored. The method of reproduction was lithography, a printing process in which the drawings were etched on long-lasting stone rather than soft metal. The price of the magazine was not cheap, but each four-page, quarto-size issue included 20 to 30 large and small images. By comparison, a single Rowlandson print in color could cost three shillings or more. This was clearly good value.

One of the factors that boosted the magazine’s success was the quality of the artwork, both in terms of Seymour’s artistry and his political insights. In Seymour’s design for the first bound volume, we see politics as an enjoyable show. He depicts John Bull, the archetypal Englishman, turning his head to us and smiling gleefully at the rout of the Tory government by the jubilant Whigs (or Liberals). Like John Bull, we are spectators gazing into the magical mirror of the political cartoon. Politicians may have power in government, but the magazine cuts them down to size.

Robert Seymour, “The Birth of Political Sin,” The Looking Glass, Nov. 1831. Seymour shows the Duke of Wellington, the hero of Waterloo and the leader of the Tories, as a character from Greek myth. Titled “The Birth of Political Sin,” the scene re-enacts the creation of the goddess Pallas Athena from the head of Zeus. The joke is that Wellington’s stubborn resistance to change had turned public opinion in favor of reform, which he and his party had opposed. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The second factor in the magazine’s success was good timing. The Looking Glassappeared during a period of political turbulence in Britain and Europe. In the wake of the French Revolution in 1830, the new Whig government in Britain introduced a modest Reform Bill designed to give more of the middle-class the vote and abolish “rotten boroughs,” where Members of Parliament could be elected by just a handful of voters. This was fiercely resisted by the Tories, who were led by the Duke of Wellington, the hero of Waterloo.

The political turmoil provided great material for Seymour. In a host of large and small cartoons, he shows Wellington and his Whig opponent Lord Brougham in various slapstick and fantastical situations. The fact that both men had large noses was another gift for Seymour, as was the pronunciation of Brougham’s name, which sounded like “broom.” In one full-page image from 1831, Seymour shows Brougham as a colossus who is about to strike the Tories (including Wellington) with his giant broom if they do not vote for reform. (The Tories did refuse to vote for reform and sparked a series of riots). The scene is funny but also disturbing, as it implies that the new government could become tyrannical.

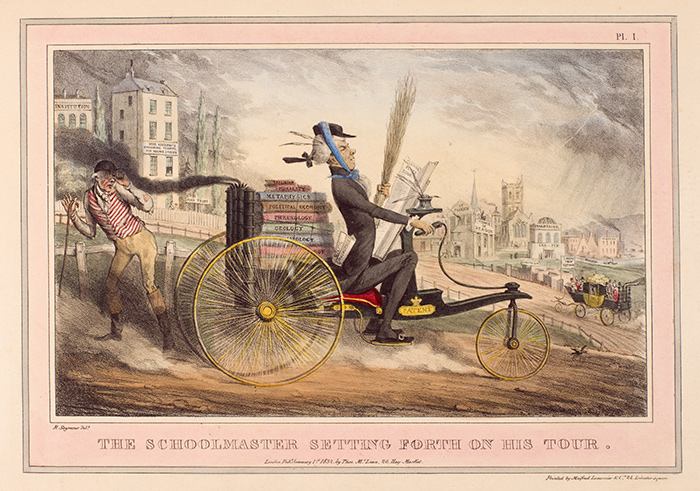

Robert Seymour, The Schoolmaster Abroad, Plate 1, 1834. Seymour mocks Lord Brougham’s role as a leading figure in working-class education. Brougham’s attempts to convert the British people to his gospel of “useful knowledge” fell on deaf ears. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

About a year later, Seymour showed the defeated Wellington as a character from Greek myth. Titled “The Birth of Political Sin,” the scene re-enacts the creation of the goddess Pallas Athena from the head of Zeus. The joke is that Wellington’s stubborn resistance to change had turned public opinion in favor of reform, but the image is also impressively crafted. Although Seymour parodies Renaissance painting, he also borrows its beauty and compositional balance.

Seymour was a prolific comic illustrator, and The Huntington has several other very rare examples of his superior artwork. One of my favorites is The Schoolmaster Abroad (1834). Brougham is the target again. In this instance, Seymour is mocking Brougham’s role as a leading figure in working-class education. But what strikes me is the energy, vividness, and joyful inventiveness of the cartoons. The first image in this book shows Brougham riding what can only be described as a 19th-century motorcycle powered by steam, his books perched perilously close to the exhaust system. Below him is a horseless stagecoach, a comic example of technological and industrial progress that resembles an object from science fiction. Needless to say, Brougham’s attempts to convert the British people to his gospel of “useful knowledge” fall on deaf ears.

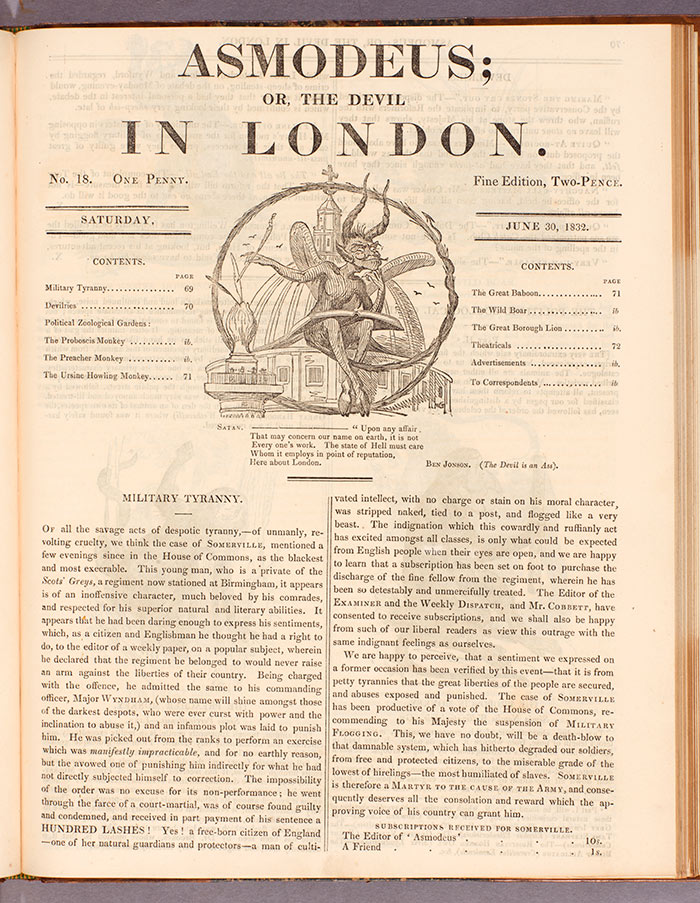

Robert Seymour, front page of Asmodeus; Or the Devil in London, June 30, 1832. Seymour reached out to a working-class readership who could afford to pay just one penny for a monthly installment of this series. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I also admire the short-lived series Asmodeus in London (1832). It shows Seymour reaching out to a working-class readership who could afford to pay just one penny for the monthly installment. In order to achieve this very low cost, Seymour turned to wood engraving, which allowed images and text to be printed cheaply on the same page.

Seymour was a gifted and astute political cartoonist. Sadly, he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1836, before he had even reached the age of 40. We are lucky to have so many examples of his fine work.

Related content on Verso:

A Decidedly British Approach to Humor (Aug. 21, 2015)

A Satirical Look at Georgian Society (Jan. 28, 2015)

Ian Haywood is professor of English Literature at the University of Roehampton in London and a 2016–17 short-term fellow at The Huntington. His books include Romanticism and Caricature and The Gordon Riots: Politics, Culture and Insurrection in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain (co-edited with John Seed).