The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Sir Isaac Newton, Alchemist?

Posted on Fri., April 10, 2015 by

In a demonstration conducted at The Huntington, William R. Newman produced a bright red metallic “tree” made of silica that grew and branched as his lecture proceeded. Detail from a photograph by William R. Newman.

Is it possible that the English physicist and mathematician Sir Isaac Newton, one of the greatest theorists in the history of science, practiced alchemy? That a giant of the scientific revolution shared a dream common among charlatans of his age—to turn lead into gold?

William R. Newman, professor of history and philosophy of science at Indiana University and the Eleanor Searle Visiting Professor in the History of Science at Caltech and The Huntington, answered these questions with a resounding yes during “Why Did Isaac Newton Believe in Alchemy?”—a Dibner Lecture held recently at The Huntington. (You can listen to the lecture on iTunesU.) He not only explained why Newton performed alchemical experiments and produced numerous manuscripts on the subject, but also intrigued the audience with live demonstrations of what appeared to be the growth of minerals and transmutation of metals.

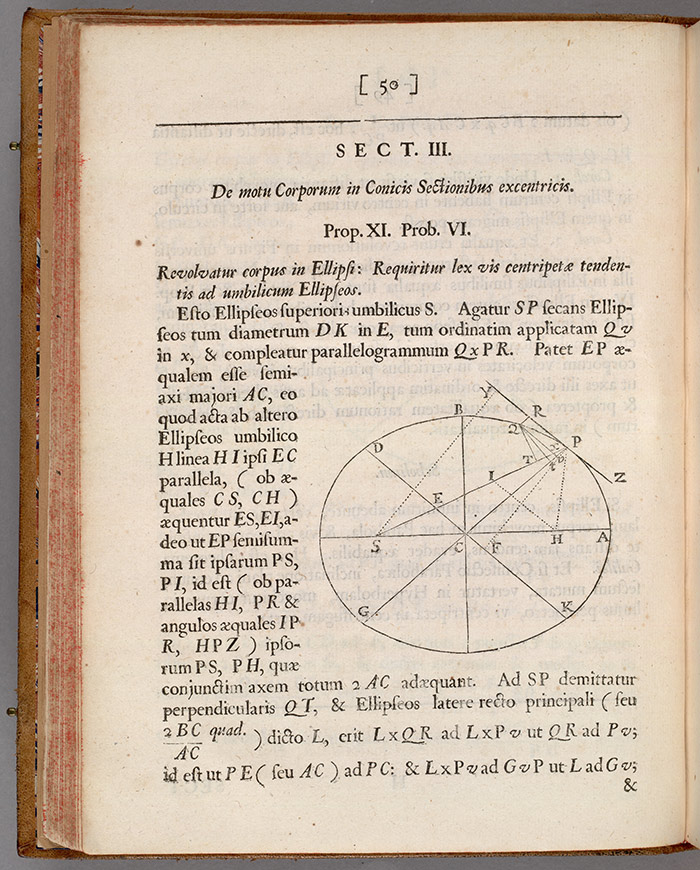

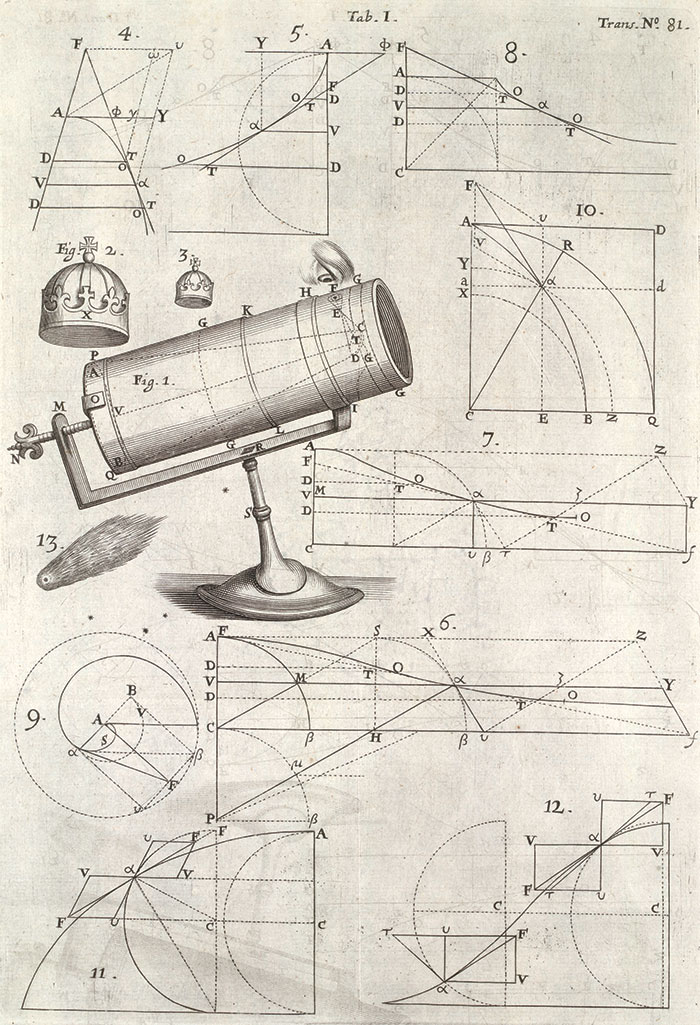

In the 21st century, the idea that Newton practiced alchemy seems surprising. If you want some quick reminders of his milestone contributions to the sciences, stroll through the Library’s permanent exhibition “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World.” Newton revolutionized astronomy through his Principia Mathematica, which provided mathematical models of the workings of the universe; he also simplified telescope design to make the observation of celestial bodies easier and less expensive. His discoveries form the basis of the modern theory of light and color, and his Opticks explained how light was composed of a spectrum of different colors that could be separated and recombined.

First edition of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles), 1687. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Newton, however, was also a man of his time (1642-1727). Some of his scientific contemporaries—most notably Robert Boyle, one of the fathers of modern chemistry—explored ideas such as the Philosopher’s Stone (also called the Sorcerer’s Stone, which readers of Harry Potter will recall from the first title in the series). The stone was a substance said to be capable of turning lead into gold, rejuvenating the aging, and even bestowing immortality.

So many eminent minds pursued alchemy, according to Newman, because there was evidence that minerals could “grow” beneath the earth as well as in a flask. Saltpeter, alum, and vitriol were all known to replenish their supply after being collected by miners. Newman, working in a lab at Indiana University, duplicated the Tree of Diana, beloved by alchemists, in which an amalgam of silver and mercury in a solution of nitric acid forms silver crystals. Newman did a similar experiment at The Huntington, using less dangerous materials, to produce a bright red metallic “tree” made of silica that grew and branched as the lecture proceeded.

Illustration of Isaac Newton’s reflecting telescope in An Account of a New Kind of Telescope, invented by Mr. Isaac Newton, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, 1672. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Public demonstrations of alchemical transmutations became popular in the 17th century, and many detailed eyewitness accounts still exist. One of the most spectacular was held at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I: a silver medallion one foot in diameter was dipped into a mysterious solution and emerged partly golden. In the 1930s, an analysis of the medallion, which resides in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, revealed that it was really an alloy of silver and gold. It’s now known that the mysterious solution used in the demonstration was concentrated nitric acid, which had eaten away at the silver to reveal the gold underneath—a process that today is called depletion gilding.

Unfortunately, despite their efforts, alchemists never succeeded in proving the principles of alchemy. “All my stories are sad,” concluded Newman.

Yet Newton never gave up his dream of metallic transmutation, even during the latter part of his life when he was in charge of The Royal Mint. Newman sees this quest not as “isolated madness but the idée fixe of the age of gold.” After all, a large, well-established literature of alchemy, coupled with demonstrations witnessed by the princes of Europe and other worthies, provided Newton and his contemporaries with a lifetime of encouragement.

This is a detail of an English alchemical scroll from the 16th century that provides a pictorial synopsis of alchemical philosophy, depicting the successive processes—through the White Stone, the Red Stone, and the Elixir Vitae—in the production of the Philosopher’s Stone. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Newton’s Lost Copy of Mede, Revealed (Feb. 25, 2015)

Newton’s Death Mask (Aug. 2, 2011)

Distilling Alchemy (Feb. 22, 2011)

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles-based communications consultant.