The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Smoothing the Path

Posted on Tue., May 13, 2014

Mary Robertson in 2013. Photograph by Martha Benedict.

There are so many reasons to thank Mary Robertson for her several decades of distinguished service at The Huntington, and many of them have been emphasized in the various celebrations of her achievements that have taken place here since her retirement in August 2013, including a tribute on Verso by her colleague Sue Hodson. These tributes have emphasized her professionalism and collegiality in the library in general and in the manuscripts department in particular, where she served most recently as the William A. Moffett Curator of British Historical Manuscripts and as the chief curator of the department. Others have also touched on the advice that she offered to a certain well-known British-based prize-winning author of historical fiction. But to those of us who make use of the manuscripts in our research as scholars, none of that really matters. Because we all know—every single one of us—where Mary’s real contribution has lain. And to those outside the world of scholarship—and I use that word advisedly—this contribution is invisible, because it is transacted quietly, without fuss, and with extraordinary accuracy and efficiency. For Mary has made the collections—what she calls the “scruffy little manuscripts,” which together make up the enormously rich Huntington holdings for the study of British history (Ellesmere, Hastings, Montagu, Stowe)—discoverable and accessible to generations of scholars all over the world.

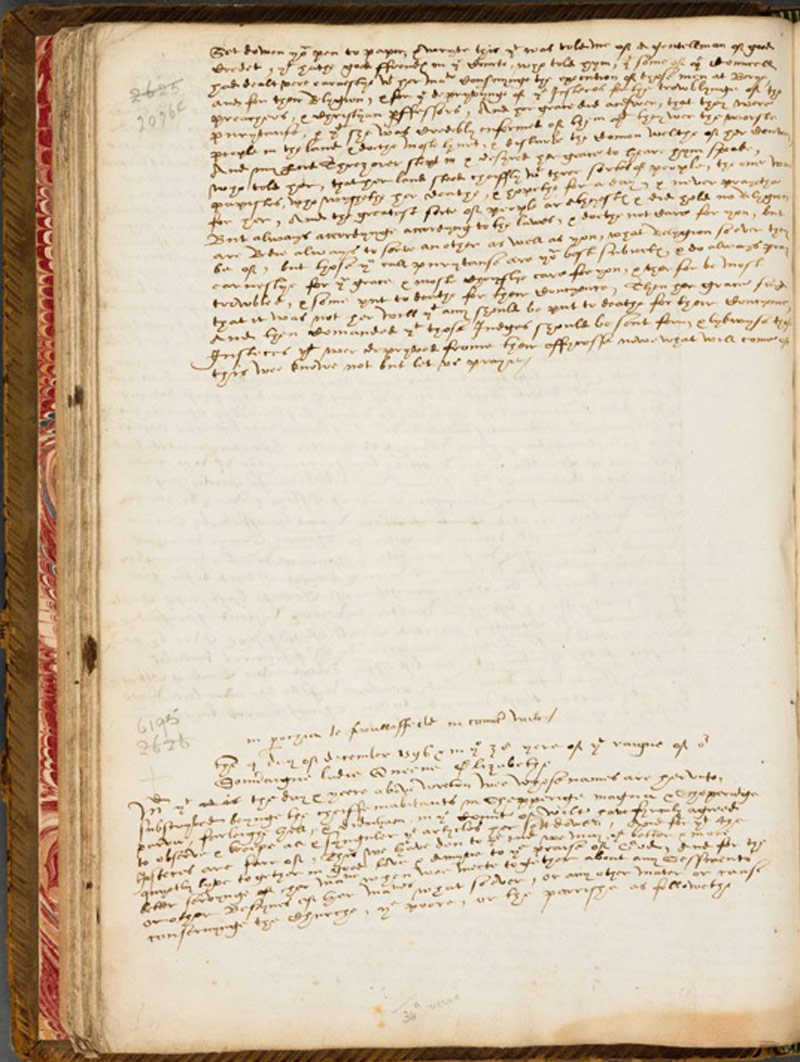

The Swallowfield articles of 1596, from The Huntington’s Ellesmere papers. Mary Robertson liked to describe such items as “scruffy little manuscripts,” but under her stewardship such documents became touchstones of some of the greatest scholarship published in the last three decades. For more on this item, see this post on Verso.

If you did a Google Books search using the terms “thank,” “Robertson,” and “Huntington,” you would come up with a staggering number of hits. I know—because recently I did just that, and the extracts that pop up make very interesting reading. Some scholars offer generic but nonetheless warm gratitude: John Beckett (1994) thanked Mary “for reading material, answering queries, and sorting through my endless list of requests for reproduction.” Others were slightly idiosyncratic: Tom Cogswell thanked her in 1998 “for not only guiding me through the darker corners of the Hastings collection but even managing to smile on the notion of establishing an East Midlands Research Center at the Foot of Mount Wilson.”

Others emphasized the energizing and galvanizing effect of her advice and enthusiasm: Thomas Kren paid tribute in 1990 for Mary “graciously playing host to one of the symposium sessions and arranging an exhibition relevant to the project.” Allan McInnes and Arthur Williamson (2006) thanked her “for immense support, first class organization, and energizing presence.” And Roger Knight and Martin Wilcox (2010) offered “thanks for her facilitating such a good start to the project.”

Some of these people had, at the time that they expressed their thanks, never even met her in person, for they were offered help remotely, so here is Maija Jannsen in 1998 thanking Mary for “taking special care that I got a copy of all of the Hastings election return.” Some guy from the history department at the University of Warwick in 1999 (yours truly) expressed gratitude “for her prompt answers to last-minute queries” and again in 2001 for “invaluable help at very short notice in arranging for the reproduction of a map.” Paul Nelson, in 2005, thanked her for her “assistance in securing copies of Hastings material for this study.”

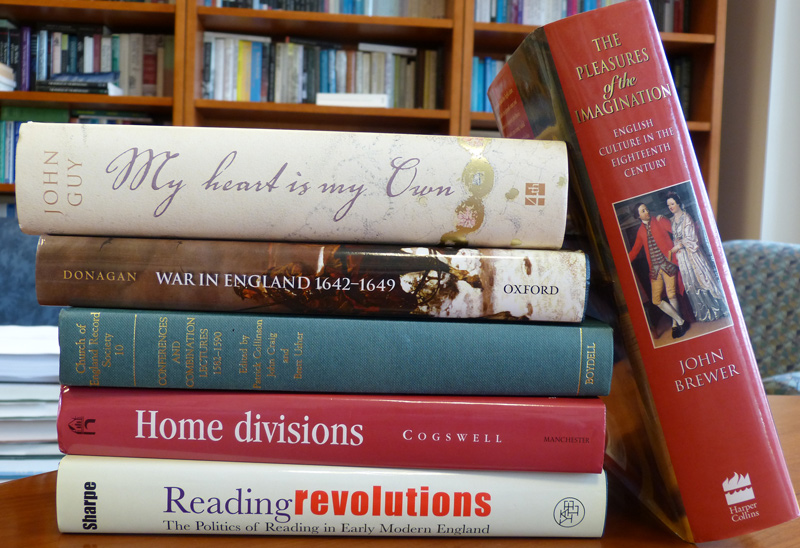

Some of the dozens of books that have acknowledged a debt to Mary Robertson: John Guy’s My Heart Is My Own: The Life of Mary, Queen of Scots (Harper, 2004); Barbara Donagan’s War In England, 1642–1649 (Oxford University Press, 2008); Conferences and Combination Lectures in the Elizabethan Church: Dedham and Bury St. Edmunds,1582–1590, edited by Patrick Collinson, John Craig, Brett Usher (Boydell Press, 2003): Thomas Cogswell’s Home Divisions: Aristocracy, The State, and Provincial Conflict (Stanford University Press, 1998); Kevin Sharpe’s Reading Revolutions: The Politics of Reading in Early Modern England (Yale University Press, 2000); and John Brewer’s The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997).

For others it was clearly a relationship of long standing: Ralph Hanna and David Lawton (2003) thanked her “for the exceptional aid we have received over the years.” And John Guy wrote in 2005 “that I gladly thank Mary who by a happy coincidence I first met in Geoffrey Elton’s Tudor seminar in Cambridge 30 years ago.”

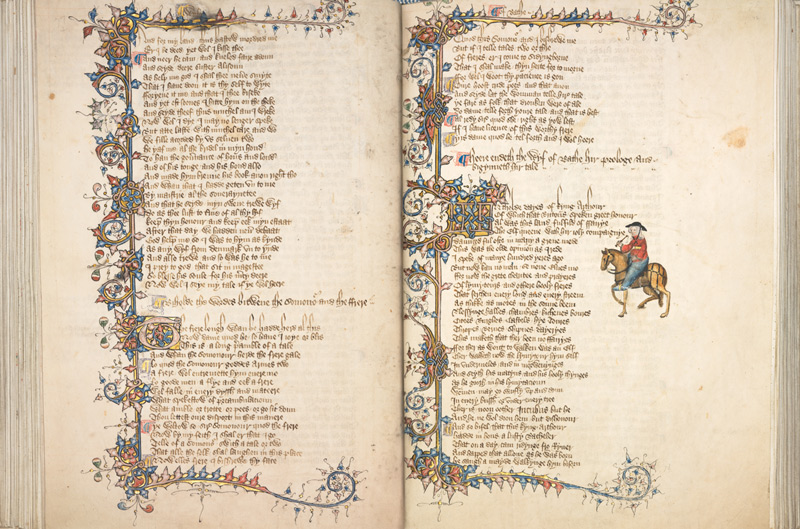

But for most it was the attention to detail and expertise she offered while scholars were in residence: Charles Owen (1991)—for “her help during the week that I spent with Ellesmere”; John Brewer (1998)—for “helping me with the Marsh diary”; Maidie Hilmo (2004)—for “spending a day with me examining the Ellesmere manuscript”; Rosemary O’Day (2007)—“I owe an especial debt to Mary for help during the periods when I have pored over the Chandos paper…her considerable knowledge of the collection was always placed at my disposal”; and Joshua Eckhardt (2009)—“for identifying [the author of the manuscript] and for confirming my understanding of his note.” She was invariably prepared to go the extra mile: Ann Astell noted in 1990 that “due to her kindness I was able to consult a microfilm of the manuscript while the original was being prepared for facsimile publication.” And Guy de la Bedoyere thanked her in 1997 “for supplying revised readings as the manuscript was not easily available for reproduction.”

And all this was executed with an extraordinary combination of professionalism, grace, and friendliness that everybody recognized: Brian Robins thanked her in 1998 “for elevating friendly help and support to new levels of meaning in an institution that combines scholarly facilities with a warmth of welcome that is unparalleled in my experience.” Anita Guerrini expressed gratitude in 2000 “to Mary Robertson and Mary-of-the-Chocolates” (’tho, frankly it isn’t clear to me if they are one and the same) “and confirming The Huntington’s reputation as a scholar’s heaven.” J. R. Milton and Philip Milton (2006) were grateful for her “doing so much to make our visit there an enjoyable one.” Bill Speck (2006) thanked her “for helping make my month in that scholarly haven pleasant as well as profitable.”

Maidie Hilmo thanked Mary Robertson for “spending a day with me examining the Ellesmere manuscript.” From the acknowledgments in Medieval Images, Icons, and Illustrated English Literary Texts: From Ruthwell Cross to the Ellesmere Chaucer(Ashgate, 2004). Above is The Huntington’s Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, open to “The Wife of Bath’s Tale.”

Then there are the poignant tributes, thanks offered by towering giants of the profession who are no longer with us: Kevin Sharpe (2000) thanked Mary “for kindly introducing me to the diary of Sir William Drake” and Patrick Collinson (2004) for “her prompt response to enquiries” and for “generously supplying a photocopy of the complete manuscript with the library’s compliments.”

She has also been an extraordinary role model to her fellow curators, not just to her successor as curator of English historical manuscripts, Vanessa Wilkie, but also to Dan Lewis, who succeeded her as chief curator of manuscripts, so he gets the penultimate citation. In the preface to his book published in 2009, Dan paid tribute to Mary as his “boss, colleague, and friend [who] offered unreasonable amounts of support in a variety of forms. Not only has she worked unstintingly for some 30 years to make The Huntington—through her scholarship and her stewardship of the collections—one of the world’s great research libraries, but has helped to make it one of the world’s best places to work as a curator.”

But the last word goes to Mary’s friend Barbara Donagan, who put it best of all in 2008, when she wrote in the preface to her wonderful book on the English civil war that “like all those who come to The Huntington, I owe an incalculable debt to Mary, whose interest, expertise, and friendship have smoothed my path.”

Writes Barbara Donagan: “I owe an incalculable debt to Mary, whose interest, expertise, and friendship have smoothed my path.” From the acknowledgments in War In England, 1642–1649(Oxford University Press, 2008).

Yes, Mary we are all, as Barbara says, in your debt. And we are now in some small measure at least, I think, able to repay you. I am delighted to announce that The Huntington has received a number of gifts that together have been used to create the Mary Robertson Fellowship in Tudor Studies, which each year will be awarded to a scholar conducting research in the history and culture of 16th-century England. So Tudor studies will continue to thrive here in the coming years. On behalf of all of us: Thank you, Mary.

This post is adapted from the opening remarks delivered on Feb. 14, 2014, at a symposium titled “Tudor History in Honor of Mary Robertson.”

Steve Hindle is the W. K. Keck Foundation Director of Research.