The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Society and Solitude in Concord

Posted on Tue., June 14, 2016 by

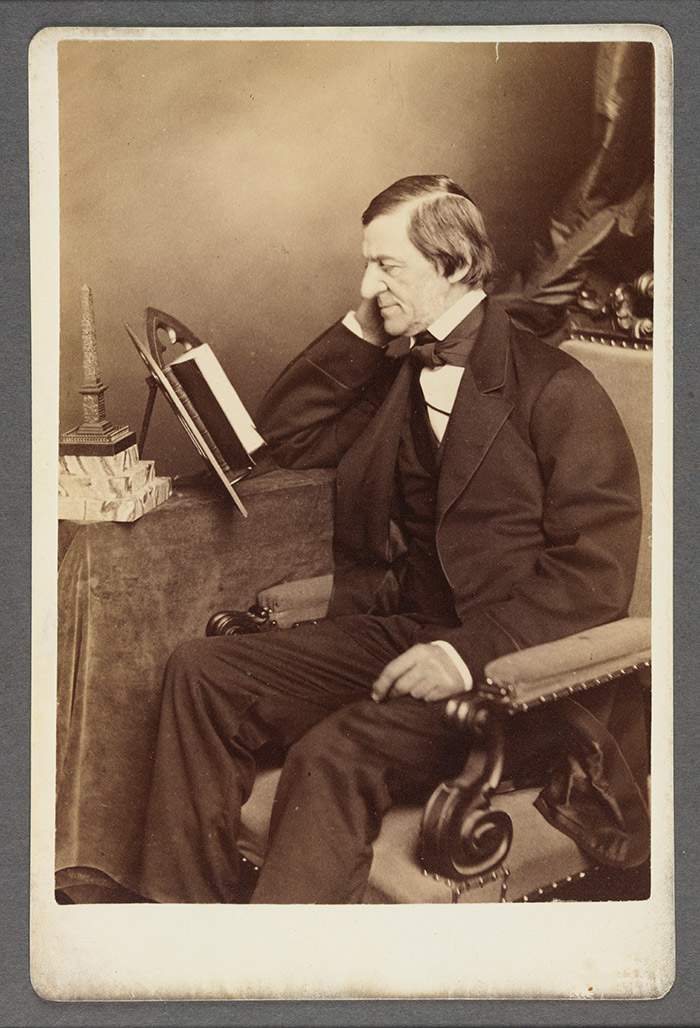

Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ca. 1860, photo by Allen & Rowell. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the middle of the 19th century, the small town of Concord, Mass., had an outsized reputation as New England’s intellectual center. This was in large part thanks to the fame of four writers who called the place home: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau.

A recent talk at The Huntington explored how these four authors (and a fifth if you count Alcott’s father, educator and philosopher Bronson Alcott) navigated a challenge that many writers face: how to strike a balance between the solitude they need for contemplation and the social interaction they seek for inspiration.

Alice Fahs—professor of history at UC Irvine and the 2015–16 Rogers Distinguished Fellow in 19th-Century American History at The Huntington—delivered the lecture, titled “The Creative Life in 19th-Century America.”

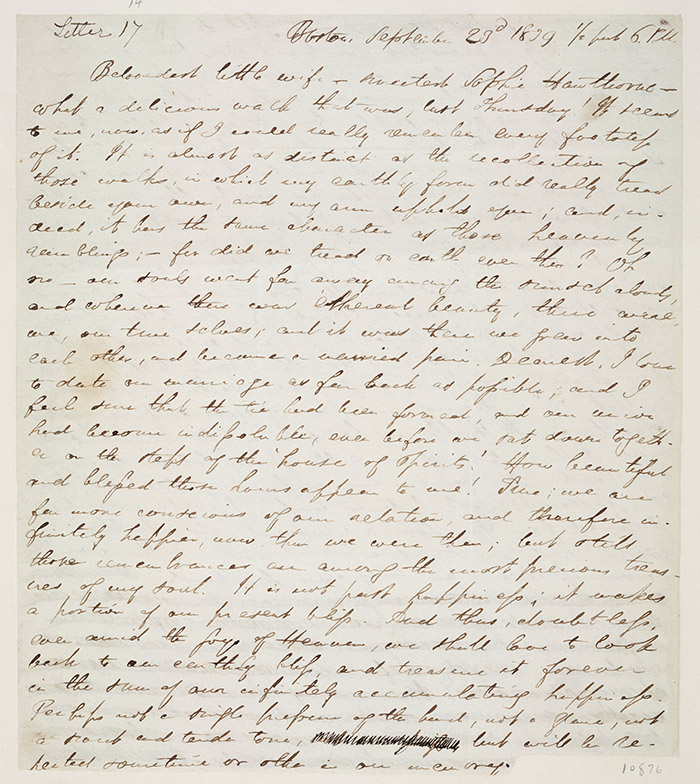

Letter from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Sophia Amelia (Peabody) Hawthorne, 1839. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

She started by quoting from “Society and Solitude,” an essay by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote of self-reliance and individualism. He stated: “Now and then a man exquisitely made can live alone, and must; but coop up most men and you undo them.” Yet, he went on to say, “… people are to be taken in very small doses.”

In Emerson’s case, the small village life of Concord, with its high concentration of thinkers, suited him perfectly. His favored walking partner was Bronson Alcott, better known today as the father of Louisa May Alcott, author of the novel Little Women.

For Alcott’s part, it is said that he so thrived on the company of people that it was something of a village sport to observe him lying in wait to intercept the famously private Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of the novel The Scarlet Letter. Indeed, Hawthorne was a notably silent attendee at Emerson’s regular gatherings. Oddly, in the days before his success, Hawthorne joined Brook Farm, an experiment in communal living inspired by the ideals of the Transcendentalists. He may have done it for financial reasons, said Fahs, in anticipation of his marriage to Sophia Peabody. The Huntington possesses a love letter Hawthorne wrote to her in which he described his time at the farm. While there were moments of excitement—“Thy husband has milked a cow!”—it’s clear the experiment was not working: “I have not the sense of perfect seclusion which has always been essential to my power of producing anything.”

Site of Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond, where visitors placed stones in remembrance, ca. 1895. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Meanwhile, Henry David Thoreau convinced generations of readers of the virtues of “a life in the woods” in his memoir, Walden. Yet even Thoreau needed social interaction, said Fahs. Far from being a remote outpost, it turns out that Thoreau’s cabin on Walden Pond was a mere mile and a half from Concord, where his family resided. Thoreau was known to go home from time to time for meals and to do laundry. He would also visit local farmers to learn about flora and fauna, and he collaborated with Emerson on The Dial magazine. Bravo, said Fahs. Thoreau’s alternating rhythm of society and solitude, Fah noted, added up to a well-constructed writer’s life that should be celebrated, not criticized.

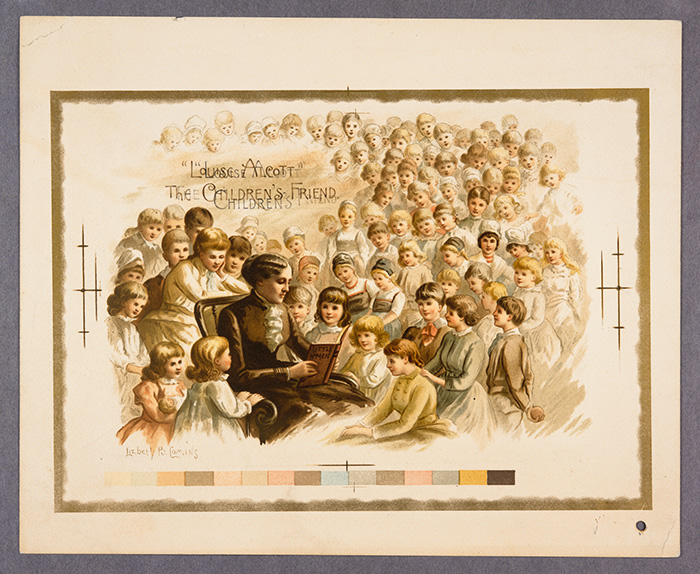

While the balance between society and solitude may challenge even today’s writers, Fahs did point out how times have changed, especially for women. Louisa May Alcott, for instance, didn’t have the freedom to go to the woods. Walks and conversation groups were the province of men. She was saddled with the drudgery of domestic duties, epitomized by bottomless piles of sewing, and had to steal time away to write. Unlike Emerson, she hated Concord, finding it “dull, boring and small-minded.” Eventually she escaped to a townhouse in Boston, where she could live anonymously, free from surveillance.

‘“Louise Alcott” the children’s friend,’ color lithograph by Elizabeth B. Comins, ca. 1888. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

So given the frenetic pace of contemporary life, how do writers of today balance society and solitude? It turns out that some of the long-term research fellows at The Huntington discovered a remarkably effective strategy involving a kitchen timer. As Fahs explained at the end of her lecture, the “Pomodoro method” comes in handy when fellows gather on the café terrace each morning before public hours. The Italian-made, tomato-shaped timer is set at intervals: 25 minutes for writing and then five minutes for talking. Those who’ve tried it say it’s the perfect mix for getting work done.

You can listen to Alice Fahs’ Distinguished Fellow lecture, “The Creative Life in 19th-Century America,” below. She is the author of several books, including Out on Assignment: Newspaper Women and the Making of Modern Public Space and The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861-1865 .

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.