The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Spirit Boys

Posted on Thu., April 7, 2016 by

Master of the Die, after Raphael, Putti Playing, engraving, 1532, 18.7 x 28.3 cm. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Wander through any major collection of European art, and you will find them in abundance. Travel to England, Germany, France, Spain, or Italy, and chances are that one will catch your eye. A winged head of curly hair with apple cheeks, sculpted in relief, emerges from the corner of a church interior. A plump, undeveloped limb tumbles over the edge of a war monument. What exactly are those little infant beings that adorn architecture, populate paintings, and swarm over heart-shaped chocolate boxes every February 14th? This is the subject of the exhibition “Spirit Boys: Infant Gods and Putti on Paper,” on view in the Works on Paper Room at the Huntington Art Gallery until July 25.

We call them cherubs, or Cupid, but their precise identity is more complex. In literary terms Cupid and cherubs originate from separate traditions. When it comes to their visual representations, however, they have evolved into subcategories of a wider class of human form. The Italian word putto means “boy” (or putti in the plural) and is used to describe the variety of naked children, almost always male, that proliferate in art.

Henry Fuseli, Venus and Cupid, pen and ink over pencil, ca. 1800, 21.6 x 27.3 cm. Gilbert Davis Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Whether cast as a Christian angel or embroiled in a pagan emblem, the figure is a spiritual being that traverses divine and earthly realms. It might be a demon, a genius, or a personification of the wind. Often it is purely decorative with no precise function. The putto is hybrid and unfixed, a synthesis of sacred and profane, high and low, ancient and modern.

Inspired by the demonic infants sprawling across ancient Roman sarcophagi, Florentine Renaissance artists employed the putto as an ornamental framing device that could animate an artwork. Putti soon took center stage, as in Putti Playing, an engraving executed by the 16th-century printmaker known as “Master of the Die” after a work by Raphael. The print reproduces an unrealized design for tapestries in the Vatican’s Sala di Constantino. The bodies of these boys, eight in total, are adult in their muscularity. They enact an allegorical scene symbolizing the power of love.

Alfred Edward Chalon, Infant Bacchus, watercolor, ca. 1850, 21.1 x 18.4 cm. (59.55.201). Gilbert Davis Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

By the 17th century, putti were everywhere. It was around this time that it became standard for angels, specifically cherubim, to appear with this same form. As the figure became a staple of painting and sculpture, it took on a younger, chubbier appearance. Flemish sculptor Francois Duquesnoy was instrumental in establishing the shift and nurturing the popularity of the putto during the Baroque period and beyond. In keeping with the appetite for Venetian painting that marked the age, he emulated the plump babies by Titian, creating a rounder, softer type of form. The Huntington is home to a bronze statue by Duquesnoy, Mercury and Cupid (1629-1630), in which a wingless infant figure at the base of the statue gazes up at the lean messenger god.

In the 18th century, the putto was implicated in the renewed interest surrounding the art of antiquity. With the excavations of the ancient sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum, artists had a fresh vision of the classical world that challenged the extravagance of Baroque taste. A drawing by the Anglo-Swiss artist Henry Fuseli (1741–1825), Venus and Cupid, reverts to the more mature putto drawn by Raphael and Michelangelo, old masters who were viewed, during the period, as mediators between ancients and moderns. The inclusion of pubic hair, however, goes against the grain of the classical ideal.

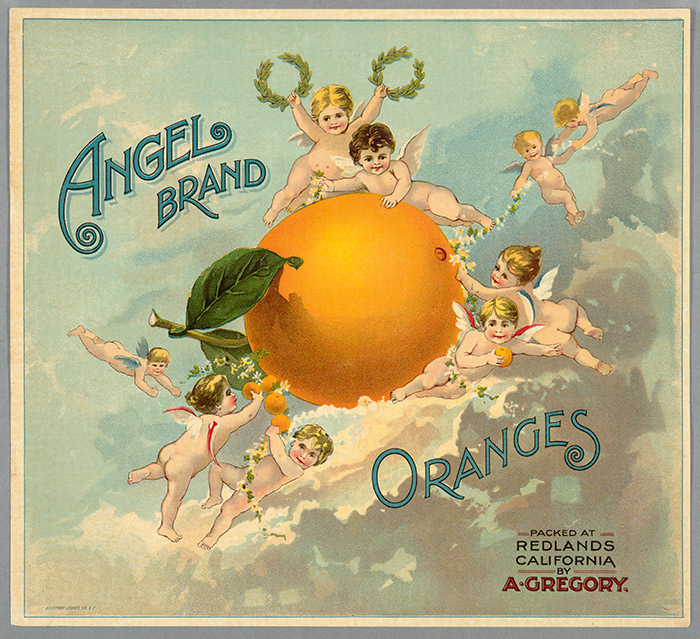

Unknown artist, Angel Brand (advertisement for oranges), colored lithograph, 1900, 25.08 x 27.62 cm. Jay T. Last Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Cupid was not the only god that could appear in infant form. Bacchus, god of wine and ecstatic visions, is another god that frequently appears in the guise of a putto or young child. Artists of the 19th century felt increased pressure to create works based on visible reality, something that would only increase with the invention of photography. The blond boy who appears in the Swiss painter Alfred Edward Chalon’s Infant Bacchus looks more like the portrait of a Victorian toddler than an ancient deity.

The early 20th century marked the official decline of visual classicism. Antiquity no longer possessed an overarching authority. Classical forms lived on in advertising, as indicated by our culture’s enduring fixation on images of ideal beauty. A turn-of-the-20th-century lithograph advertises “Angel Brand” oranges grown in Southern California. Little boys orbit a giant fruit, their association with European art infusing the commodity with Old-World glamor.

These figures have more of an affinity with the fleshier Baroque putto than his slimmer counterpart. It is this more corpulent form that remains visible in the postmodern iconography of Valentine’s Day.

Cora Gilroy-Ware is a 2015–16 Fellow in the Caltech-Huntington Program for the Study of Materialities, Texts, and Images.