The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

"A Stern Mandate of Duty"

Posted on Fri., Feb. 21, 2014 by

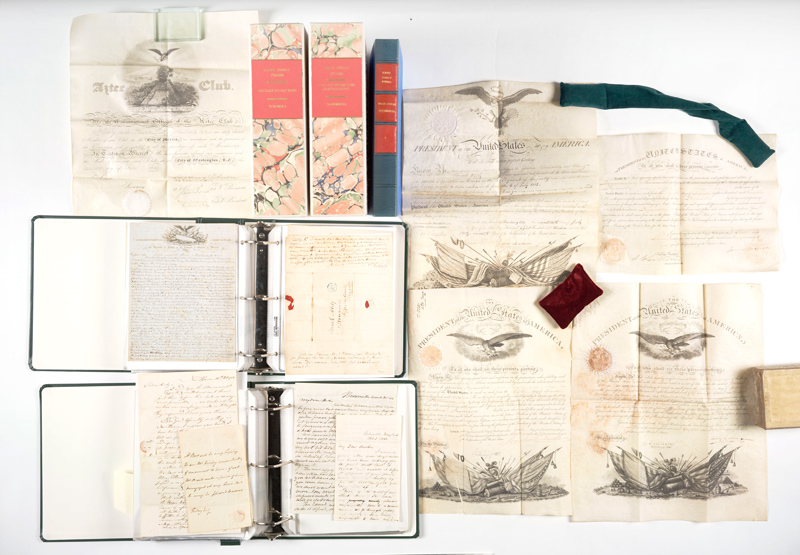

A selection of items from the newly acquired Kirby collection. The letters shown in the lower left are detailed below. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the greatest perks of a manuscript curator's job is meeting, in a manner of speaking, the nicest people who are no longer with us. I guess this is why we look at the past with such nostalgia: Much of the primary sources, such as letters home, were written predominantly by nice people. (Cads tended not to write home: It seems they did not feel the need to keep in touch with their families, did not have many friends, or were too busy being jerks.)

It has been my privilege and pleasure to meet Edmund Kirby (1794–1849), the senior paymaster (military accountant) on the staff of Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott during the Mexican War. Last month the Library Collectors’ Council purchased a collection of his letters.

Kirby, a veteran of the War of 1812, was assigned to Taylor’s headquarters in the summer of 1846 and was later transferred to the command of Winfield Scott. As seen from the letters, he opposed "Mr. Polk's War" from the very beginning. Yet, a strong sense of what he called "a stern mandate of duty" made him rebuff all attempts by his family and friends to have him assigned to a more quiet post. He insisted that he would leave the army only if "ordered out." Although he was a mere paymaster, Kirby took part in all the major battles of the Mexican War. At the end of the war he would be awarded the rank of colonel for his bravery at the battles of Contreras and Churubusco (paymasters were not otherwise entitled to a rank higher than major).

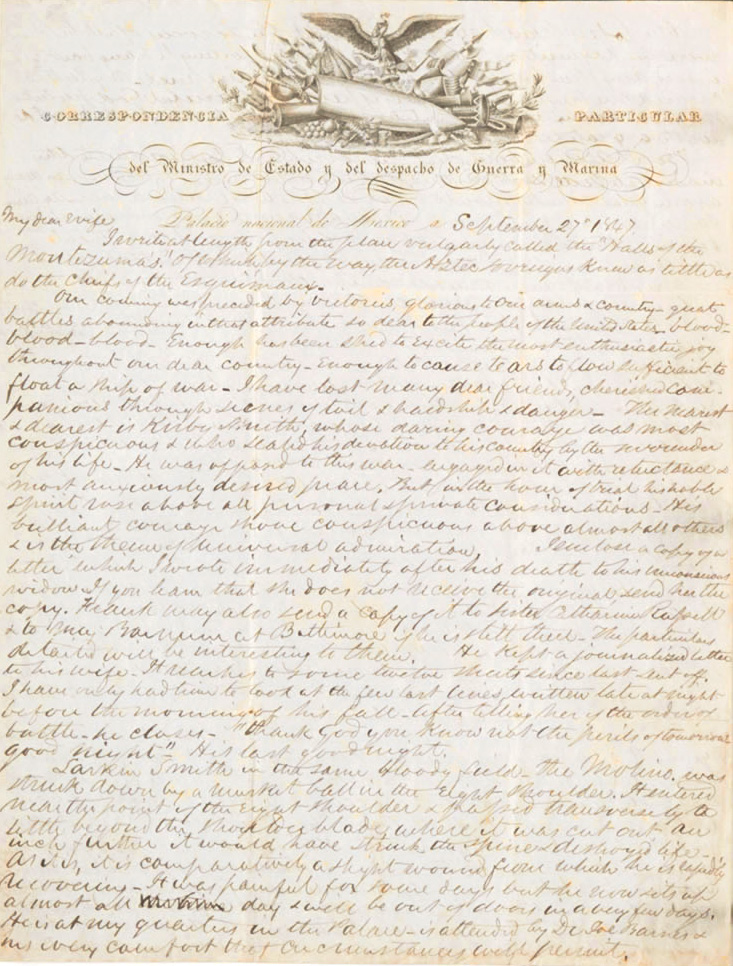

In September 1847, he wrote to his wife, Eliza, from the National Palace in Mexico City. In an acerbic aside, he mentioned that he was writing from the place that the pro-war crowd “vulgarly” styled ”the Halls of the Montezumas of which by the way, the Aztec knew as little as do the chiefs of the Esquimaux [Eskimo].” Kirby continued: “Our coming here was preceded by victorious, glorious to our arms & country great battles abounding in that attribute so dear to the people of the United States—blood—blood—blood. Enough has been shed to excite the most enthusiastic joy throughout our dear country—enough to cause tears to flow sufficient to float a ship of war."

After the battle of El Molino del Rey (Sept. 8, 1847), he found himself in "the archiepiscopal Palace converted into a hospital. The floors of the spacious apartments were covered with wounded officers & men to the extent of many hundreds, who were suffering horrid agonies, while the whole corps of Surgeons were actively engaged in amputating limbs, some of the victims screaming with agony while others sustained themselves with heroic fortitude. I saw the amputated limbs quivering with life while the gutters of the court were filled with streams of human blood. It was most sickening & enough to cure any man a taste for war.”

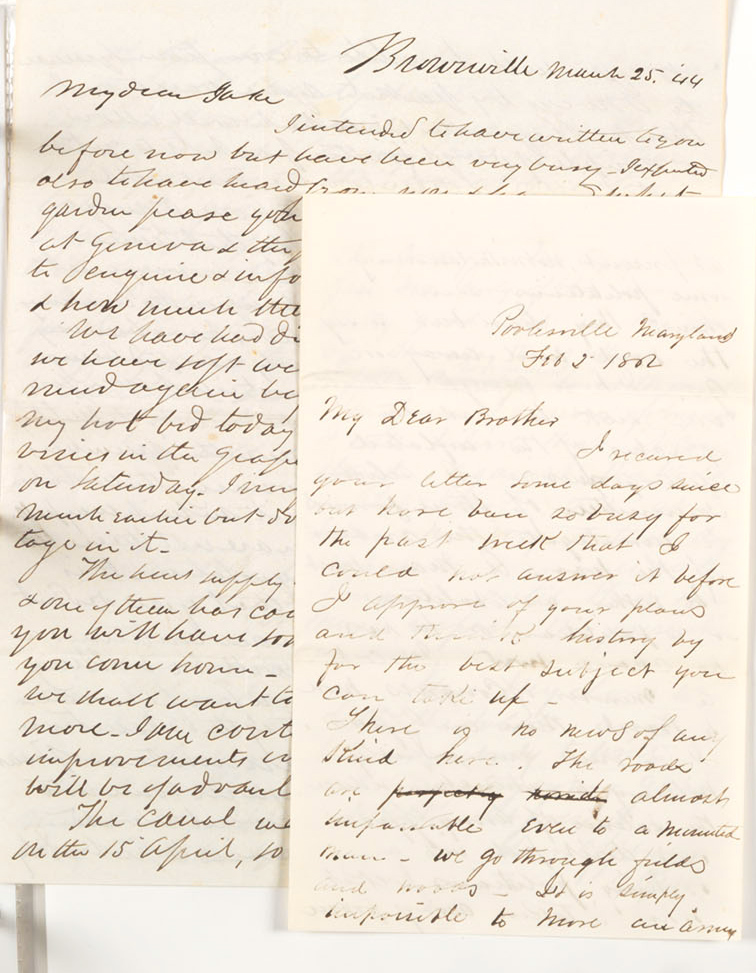

The horrors of war and loss of his friends and family (among those who perished in the battles preceding the occupation of Mexico City was his own nephew) was compounded by the intense longing for his family back in Brownville, N.Y. This longing is palpable in the letter that he wrote in October 1847. Kirby, 53 years old, had been away from home for two years; his youngest son, Marvin, was just four years old:

"Well little ones stand up & let me look at you. First comes chubby little Marvin who looks at me hard but don’t know me but he likes the looks of my bright soldier buttons & takes a look at my sword. We shall be good friends soon. Then there is little Kitty Clover & gives me a kiss & wants a piece to buy some candy. Hurrah Ned—you look as if you had been playing in the garden—rather dirty & barefooted at that. But Lady Mary makes it up for the looks as if she had just stepped out of a band box. Interruption upon interruption—I must postpone my review without looking in Jojo’s blue eyes.”

His orders finally arrived on Feb. 2, 1848, on the very same day when the peace was finally concluded. It took him six more months to embrace his family. He returned home to a hero’s welcome in August 1848. Less than a year later, he died of a disease he had contracted in Mexico.

Fast forward eleven years. His son Edmund, or “Ned,” was finishing his studies at West Point. Daughter “Lady” Mary indeed attained ladyship: She married John Contee Fairfax, the 11th Lord Fairfax and the only British peer with American citizenship, and they resided on Fairfax’s Virginia plantation. Katharine (Kitty Clover) and Josephine (JoJo) were living at home with their ailing mother, and Reynold Marvin (“chubby little Marvin”) was preparing to leave for college. He would later become a Episcopal minister; in 1886 he was appointed bishop of Salt Lake City, but refused the honor due to family circumstances.

The collection includes a group of letters from Ned to Marvin—dispensing brotherly advice, describing cadets’ life at West Point, and discussing the increasingly turbulent national politics. Ned graduated from West Point in March 1861 and immediately joined the Union Army. He was mortally wounded in the battle of Chancellorsville and died in a Washington hospital in May 1863, the same day that President Lincoln commissioned the 23-year-old Lieutenant Brigadier General of Volunteers so that Ned’s widowed mother and young siblings could receive a more generous pension.

This extraordinary collection of a remarkable military family has found a perfect home at The Huntington. I will be forever grateful to the Library Collectors’ Council for purchasing this collection, as will many historians of antebellum and Civil War America.

Welcome home, Colonel Kirby!

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.