The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Study for Gassed

Posted on Thu., Aug. 7, 2014 by

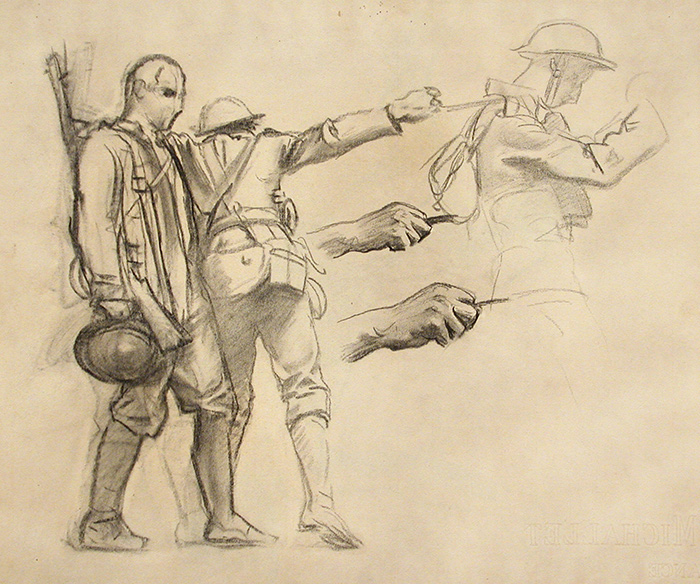

The men depicted in John Singer Sargent’s Study for Gassed, ca. 1918–19, are rendered in the final painting (below) third and fourth from the left. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Since the opening of The Huntington’s exhibition of spectacular World War I posters in the West Hall of the Library, we’ve taken note of a very different and sobering depiction of World War I currently on view in the Chandler Wing of the Scott Galleries.

The World War I posters on view through Nov. 3 were created to energize and excite: bold, colorful, and graphically pungent, they encouraged enlistment, investment in the war effort, and other patriotic behavior. The war effort was a good thing.

A close-up view of Gassed (below) shows the pair of soldiers from the study, now among their injured comrades.

But an artwork in the Chandler Wing provides more of a reality check on the heinousness of war—from the experiences of the renowned portrait artist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), no less. In a corner of the gallery, tucked among an exhibition of American prints, is one of Sargent’s studies for his monumental painting Gassed, completed in March 1919, and now at the Imperial War Museum in London.

The study shows two soldiers together: one appears to be doubling over or stumbling from the effects of mustard gas exposure as the other man holds him up with one arm. In the final 7.5-by-20-foot painting, the men depicted in the study are in a line of injured soldiers, their eyes bandaged after being blinded by gas. Led by orderlies, they make their way forward while holding on to one another. In the foreground lie dozens of dead and wounded soldiers. These images are in stark contrast to the background, where an almost imperceptible group of uninjured soldiers play soccer as the ravages of war are so close at hand.

The British War Memorials Committee of the British Ministry of Information commissioned Sargent to document the war showing Anglo-American cooperation. In July 1918, the artist visited the Western Front to spend time with British and American troops. A recent New York Times article mentioned that Sargent “originally envisioned painting a homage to gallantry. But in France, he visited a field hospital crowded with soldiers who had been exposed to mustard gas, a poison that burned the body inside and out.” The experience in August 1918 so affected Sargent that he immediately changed the theme of the commissioned work.

Fellow artist Henry Tonks had travelled to France with Sargent. Recalling the event later in a 1920 letter (and quoted in the Imperial War Museum's label for Gassed), Tonks wrote, “After tea we heard that on the Doullens Road at the Corps dressing station at le Bac-du-sud there were a good many gassed cases, so we went there. The dressing station was situated on the road and consisted of a number of huts and a few tents. Gassed cases kept coming in, lead along in parties of about six just as Sargent has depicted them, by an orderly. They sat or lay down on the grass, there must have been several hundred, evidently suffering a great deal, chiefly from their eyes which were covered up by a piece of lint. Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes.”

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Gassed, 1919, oil on canvas, Imperial War Museum, London. © Imperial War Museum (Art.IWM ART 1460).

Sargent’s painting reminds us of the number of fallen soldiers in World War I: the war claimed the lives of some 9 million combatants. The Huntington’s study for the painting is but a tiny portal into that experience, and yet it is haunting and dramatic in and of itself.

For two very different World War I experiences at The Huntington, take a look at the posters in the Library and then check out the Sargent drawing. They provide fascinating juxtapositions: war as romance, nationalism, and industry on the one hand; war as pain and suffering on the other. And while they seem remarkably contradictory, in fact, they are ultimately pieces of the same story told over, and over, and over again.

Study for Gassed is on display in “Highlights from the American Drawings and Watercolors from The Huntington’s Art Collections” in the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. The exhibition is on view until Jan. 5, 2015, although many works will be rotated in October 2014.

Susan Turner-Lowe is Vice President for Communications at The Huntington.