The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Symbolism in Medieval Lists

Posted on Mon., Jan. 18, 2016 by

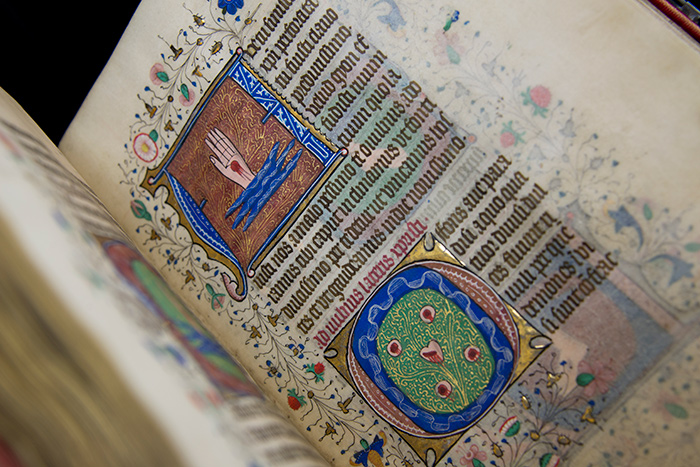

Detail from Book of Hours, Sarum use, Flanders, mid-15th century (HM 1144). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

As a teenager, I thought it would be fun to collect lists, especially the kind that are known by their numbers: the 10 essentials for day hiking, which I learned as a Girl Scout, or the 12 ways that Wonder Bread helped build strong bodies, a list I liked even though TV ads never specified the 12. My interest in lists persisted and eventually met its match when I discovered the Middle Ages and its abundance of lists with numbers in their titles: from the four evangelists to the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus to the 15 signs of doomsday, here was a trove of lists to occupy a would-be collector of lists for quite some time.

The number in a list’s title, I soon understood, was the key to remembering its contents. Considering the five senses, for instance, I can assign one sense to each of the five fingers on one hand and be certain that I’ve listed them all. But for those living in medieval times, numbers also had symbolic significance. In keeping with the five senses, the number five symbolized the body, including the most important body to medieval Christians, the body of Christ. Christ’s body and blood were the spiritual focus of the church’s highest rite, the Eucharist. The visual focus of parishioners partaking of that sacrament was a crucifix, upon which they could easily count five wounds: one in each of Christ’s hands and feet made four and another in his side made five.

Page from Book of Hours, Sarum use, Flanders, mid-15th century (HM 1086). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As the quintessence of Christ’s bodily sacrifice, the five wounds inspired many poems, prayers, and works of visual art, some of which involved additional lists of five. Compilations of lists are everywhere in the literature of medieval Christianity, and given the symbolic value and mnemonic utility of key numbers, it is easy to see why there are multiple lists using the same number. Such compilations are usually instructive: for instance, the pairing of the seven deadly sins with the seven heavenly virtues forms a set of directions for combatting vice with virtue.

Other compilations are surprising and delightful for the way they forge imaginative connections across the categories they bring together. Such is the case with a set of prayers on the five wounds that can be found in several books of hours in The Huntington’s collection of medieval manuscripts. These prayers pair the list of Christ’s wounds with a list of five rivers: the river of paradise and the four rivers that flow from it. The wounds of the hands correspond to the rivers Pishon and Gihon; the wounds of the feet, to the Euphrates and the Tigris. The side wound relates to the river of paradise itself, for just as the side wound is near the pulsing source of all five wounds (Christ’s heart), the four other rivers emanate from the river of paradise. According to Genesis 2.10, those four rivers are the source of all the rivers in the world. With this biblical geography in mind, worshipers could envision the wounds in Christ’s four extremities as rivers of redemption that irrigate the far reaches of the planet.

Detail from Book of Hours, Sarum use, Flanders, mid-15th century (HM 1086). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

This set of prayers was written in Latin, putting its analogies beyond the reach of some readers. For them, a series of images that sometimes accompanied the prayers provided an intriguing visual translation. These miniature paintings, which appear in two of The Huntington’s books of hours, depict each wounded hand and foot separately, and juxtapose each with a minimalist representation of water. Visually arresting in their own right, they are even more powerful when considered in light of their symbolism, for they suggest not only an analogy, but also an anatomical connection between the flow of the four rivers of paradise and the flow of blood from Christ’s wounds, a connection that also intimates a passage to paradise through worship of the wounds.

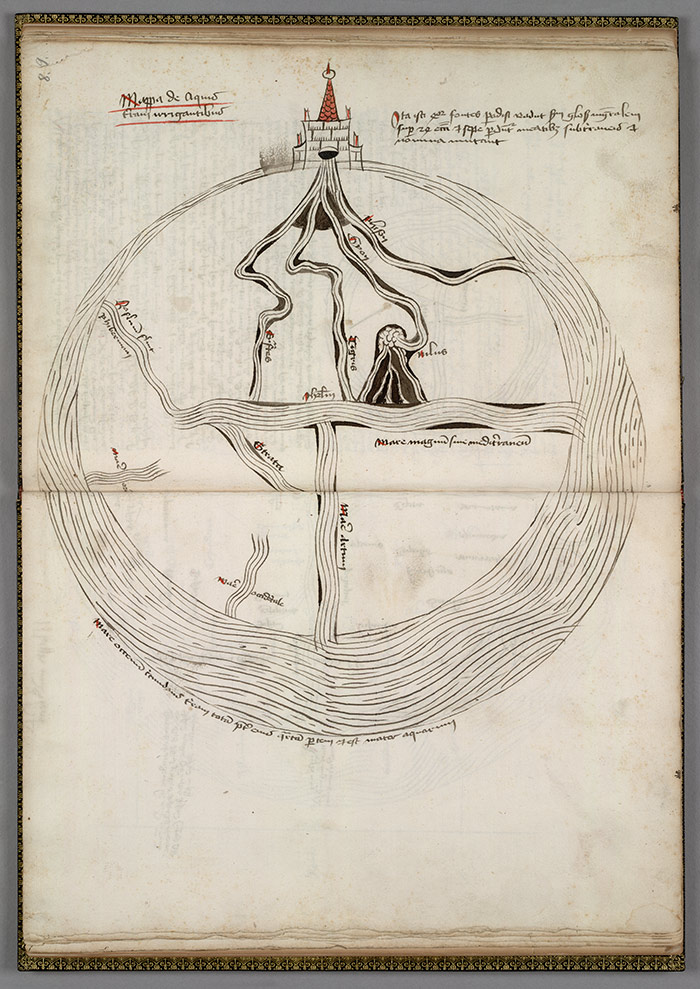

Map of rivers of the world, from Cosmography; astrological medicine, 1486–1488 (HM 83). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The image that accompanies the prayer to the side wound makes good on this intimation, for it depicts all five wounds inside a circle of blue meant to represent the river of paradise before it divides into four. The first word of the prayer to the side wound is “Oh” (“Oh font of paradise, from which divided, four sweet rivers flow”), with the circle of blue doubling as the letter “O,” effectively drawing worshipers into paradise.

This image of all five wounds also asks worshipers to consider the meaning of the number five, for along with picturing the wounds, it is also clearly a picture of the number itself. In fact, the pattern of their arrangement, with one at the center and the other four defining a square, brings to mind the pattern of five dots on a die. This evocation of a die in the pattern of Christ’s wounds reminds a discerning Christian that, in his human embodiment, Christ redeemed those five senses and, with them, the number five.

Detail from Book of Hours, Sarum use, Flanders, mid-15th century (HM 1086). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

Martha Rust, associate professor of English and director of the Medieval and Renaissance Center at New York University, is a National Endowment for the Humanities fellow at The Huntington. She is the author of the book Imaginary Worlds in Medieval Books: Exploring the Manuscript Matrix, available from Palgrave Macmillan.