The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Thomas Pennant’s Literary Appeal

Posted on Thu., April 28, 2016 by

Title page of Thomas Pennant’s British Zoology. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

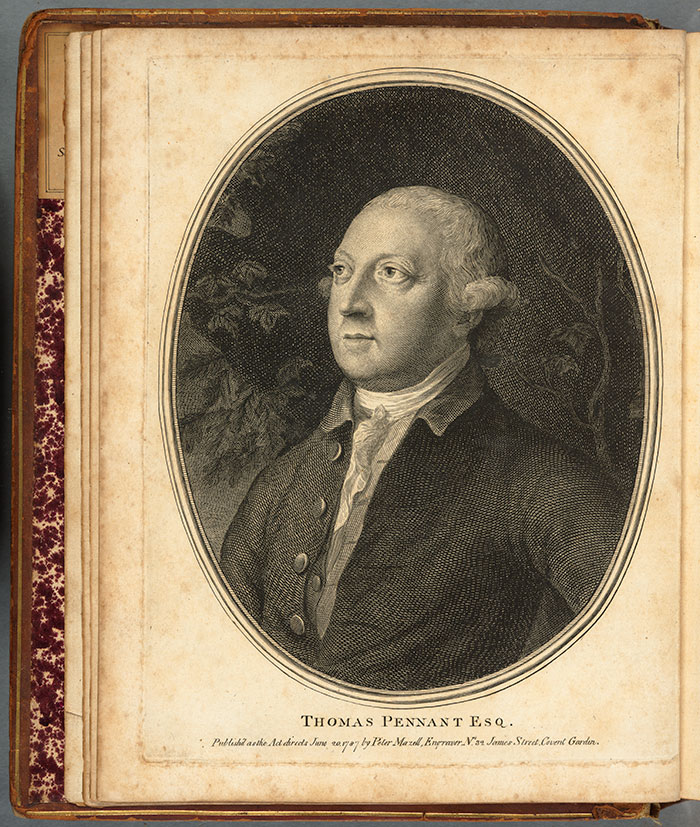

Asked to name the most famous European naturalists of the 18th century, most scholars would probably choose Sweden’s Carl Linnaeus and France’s Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon. One figure often overshadowed by these contemporaries but deserving further attention is the British naturalist Thomas Pennant (1726–1798). I’ve been researching how British women writers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries engaged with natural history—especially in the developing disciplines of botany, zoology, and geology—and I’ve been struck by Pennant’s singular importance to these authors.

The Huntington holds 45 editions of this prolific naturalist’s works, including such wide-ranging books on natural history as British Zoology (1776–77), The History of Quadrupeds (1781), Genera of Birds (1773), and Arctic Zoology (1784–87), as well as travel writing about England (1790), Scotland (1771), and Wales (1778).

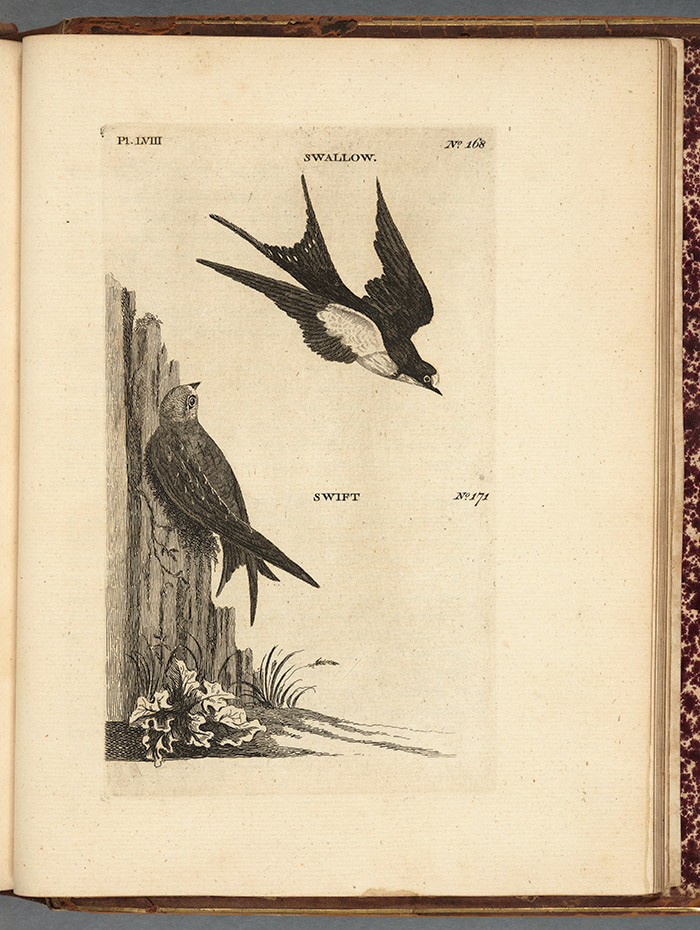

Illustration from Pennant’s British Zoology. The migrations of birds, and particularly of swift and swallow species, fascinated Pennant, Gilbert White, and other 18th-century European naturalists. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The late 18th-century poet Charlotte Smith called Pennant “the British Pliny,” and another poet, Anna Barbauld, drew on his natural history texts for her verse. Barbauld’s brother, John Aikin, dedicated to Pennant his Essay on the Application of Natural History to Poetry (1777), in which Aikin urged poets to versify Pennant’s descriptions of zoological species. Pennant may well be best known as one of the two naturalists to whom Gilbert White addressed his correspondence, especially about bird migration, in The Natural History of Selborne (1788).

Creative writers and artists, particularly women, found Pennant’s texts of great interest. In his Preface to British Zoology, Pennant described how natural history supplied artists with the materials to make the paints as well as the subjects of many paintings and noted that painters needed to be informed about natural history to depict nature accurately. Moreover, Pennant stated that descriptive poetry was more indebted to natural knowledge than either painting or sculpture because the poet’s art cannot "exist without borrowing metaphors, allusions, or descriptions from the face of nature, which is the only fund of great ideas.”

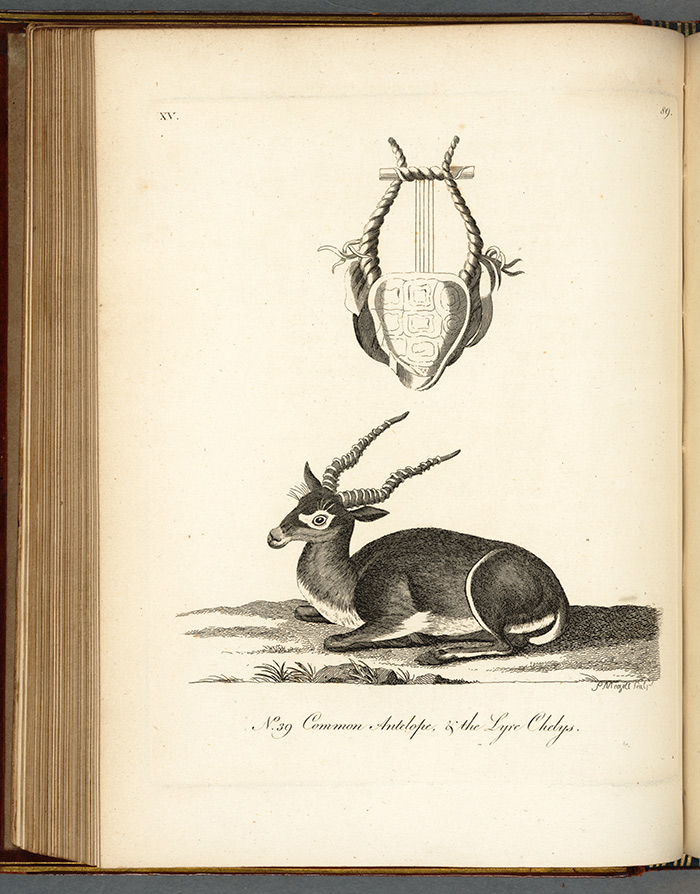

Illustration from Pennant’s History of Quadrupeds. In his description of the antelope, Pennant notes the use of this species’ horns in the production of some lyres—an instrument associated with song and poetry—and quotes verses from the Roman poet Horace. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Pennant also appealed to women writers because, unlike some other naturalists, he “wholly omitted the anatomy of animals,” and thus his work leant itself more easily to public expectations of feminine propriety. At a time when even plant anatomy was thought by some contemporaries to be too risqué for women’s study, Pennant’s delicate treatment of this aspect of zoology provided women with a framework for addressing animal and bird studies while maintaining a sense of decorum.

In addition, Pennant gained the approval of British audiences because he anchored his pursuit of natural history firmly in natural theology—asserting that the study of nature is the study of God—and in British nationalism. He argued that “the study of natural history enforces the theory of religion and practice of morality.” By persuading his fellow “countrymen” to join these nationalist, naturalist pursuits, Pennant challenged the scientific and economic prowess of the countries of his counterparts Linnaeus and Buffon. For Pennant, British exertions in natural history gave the nation “the superiority over [the] so much boasted productions in Sweden,” and he urged that, in terms of the rival French, “we should attend to every sister science that may any ways preserve our superiority in manufactures and commerce.”

By aligning themselves with Pennant’s work, British writers imbued their own texts with claims to usefulness, piety, and patriotism.

Portrait of Pennant that serves as the frontispiece for his British Zoology. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Melissa Bailes, assistant professor of English at Tulane University, is a 2015–16 Barbara Thom Postdoctoral Fellow at The Huntington.