The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Toast to Vesalius

Posted on Thu., Dec. 11, 2014 by

Visitors to the Library’s permanent exhibition “Beautiful Science” can see an original plate from Epitome, then touch the copy, imagining how medical students of the time peered into the body.

As champagne corks pop on Dec. 31 to welcome the New Year, many in the field of medicine will be raising a glass to Andreas Vesalius (1514–64), born 500 years ago on this day. A Flemish-born anatomist and physician, Vesalius wrote one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body, 1543). Among those celebrating will likely be many of the participants at “Vesalius & His Worlds: Medical Illustration during the Renaissance,” a conference being held at The Huntington from Dec. 12–13, 2014.

“The Renaissance was a turning point in medical illustration,” said Jeanette Kohl, associate professor of art history at the University of California, Riverside and the conference convener. “Artists began using direct observation, including dissection, to understand anatomy, instead of relying on classical texts,” said Kohl. The conference brings together rare book collectors, curators, art and cultural historians, and physicians to explore the changing concepts of the human body from the early Renaissance to the 17th century, using the work of Vesalius as a point of departure.

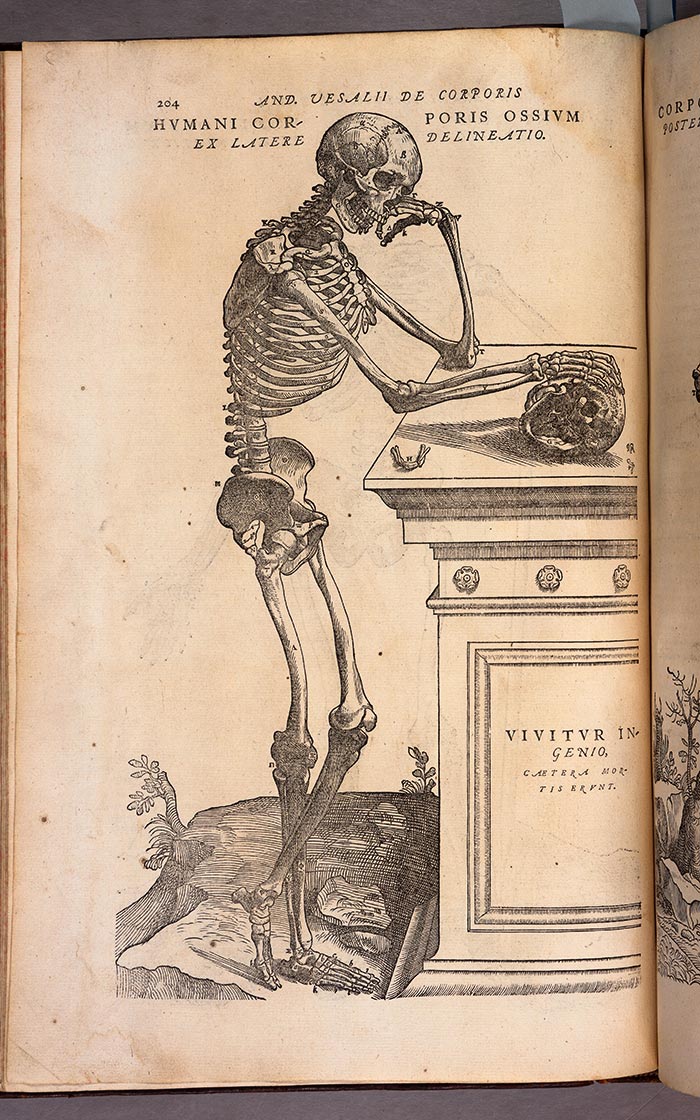

The text on the sarcophagus from this 1555 edition of De humani corporis fabrica reads “Vivitur ingenio, catera mortis erunt” (“Genius lives on, all else is mortal.”) The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica was a groundbreaking work, containing highly detailed drawings showing the organs and structure of the body. The Huntington owns a first edition of De fabrica and a shorter, more affordable student version published the same year, called Epitome. This illustrated summary of the larger work contains two plates with layered flaps that could be cut out and re-assembled to understand the placement of internal organs. One of these is on view in The Huntington’s permanent exhibition “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World.” A facsimile with movable parts lies next to it, where visitors can return to the days of Renaissance, imagining the excitement of peering into the human body, albeit virtually, one layer at a time.

The Huntington also holds two second editions of De humani corporis fabrica, published in 1555, the second of which came from the Burndy Library, a collection acquired in 2006 and composed of some 67,000 rare books and reference volumes in the history of science and technology.

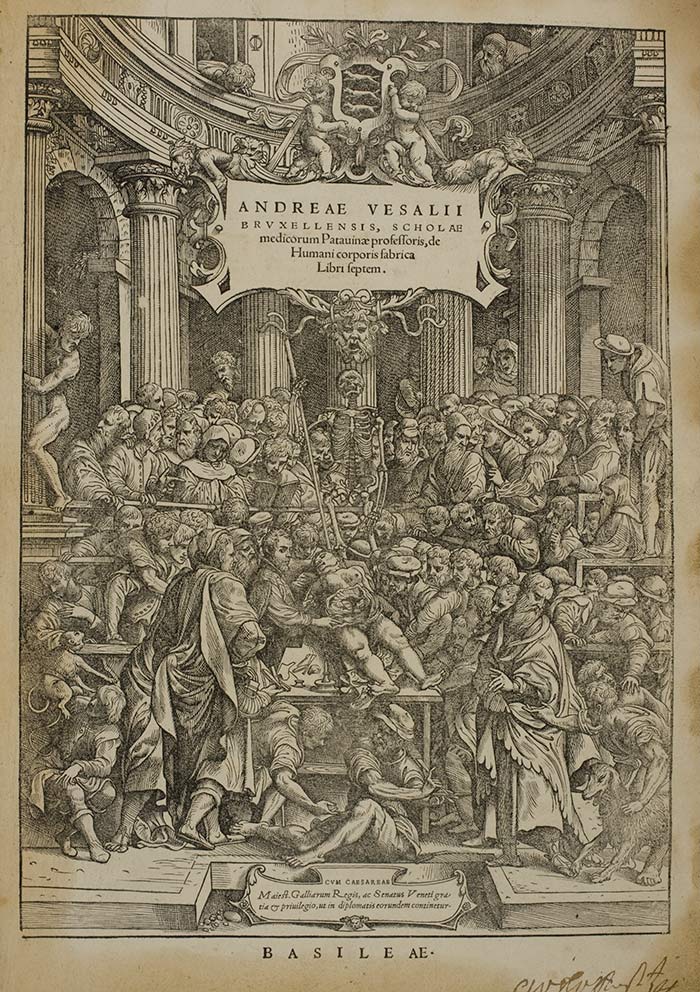

On the title page of the 1543 De humani corporis fabrica, Vesalius performs a dissection in an anatomical theater in Padua, Italy. Did John Stephen van Calcar, a pupil of Titian, make this illustration? The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Renaissance saw artists such as Titian (c. 1448-1576), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), and Michelangelo (1475–1564) conducting their own investigations into how to depict human anatomy. Da Vinci was said to have dissected human corpses as part of his artistic training. So did Michelangelo, a detail used to dramatic effect in Irving Stone’s 1961 biographical novel, The Agony and the Ecstasy, in which the driven artist sneaks around the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence, dissecting bodies supplied by a friendly prior.

Yet it was Vesalius who gathered the evidence and then systematically challenged the teachings of classical authorities such as Greek physician Galen (Aelius Galenus, 129–ca. 216). For centuries, Galen dictated certain beliefs about anatomy, even when there was little evidence to prove them.

As chair of surgery and anatomy at the University of Padua, Vesalius dissected bodies in front of his students, encouraging direct observation as the only reliable practice. This work led Vesalius to conclude that Galen must have used animals for his dissections, not humans. Vesalius made several corrections to the beliefs of his day, showing for example that the human sternum had three, not seven segments, and that blood vessels originated in the heart, not the liver. Still, when it came to organizing the seven books of De Fabrica, Vesalius respected the order imposed by Galen: bones, muscles, veins and arteries, nerves, viscera, heart, and brain.

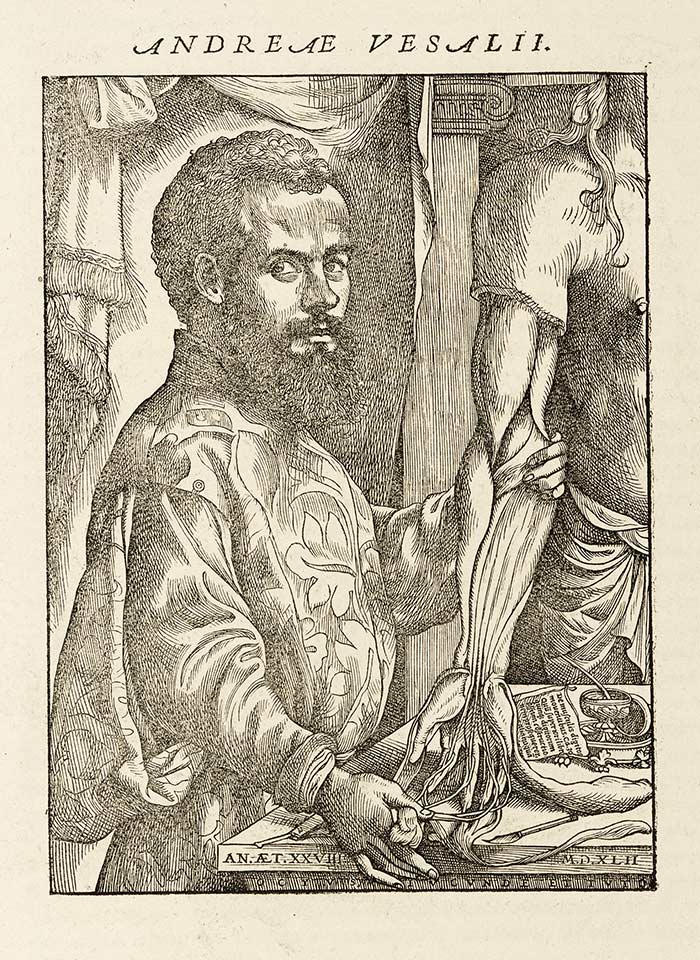

Only 28 when he published De humani corporis fabrica in 1543, Vesalius is considered the founder of modern human anatomy. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the elements that set De Fabrica apart from other works of anatomy was the exquisite detail and refinement of its drawings. Debate continues regarding who illustrated the books, with many believing it was John Stephen van Calcar, a pupil of Titian, who had produced three drawings for an earlier Vesalius work, Tabulae Anatomicae Sex (1538). Evidence, however, is limited.

The Huntington holds a preliminary pen drawing, a so-called third or last stage, for the frontispiece of De Fabrica, signed “Joh. Stephanus. inv. 1540 Venetiis.” The work has been under careful scrutiny to assess its authenticity.

Might this week’s conference reveal new evidence?

Diana W. Thompson is a freelance writer based in South Pasadena, Calif., and a regular contributor to Huntington Frontiers magazine.