The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Union Forever

Posted on Tue., March 31, 2015 by

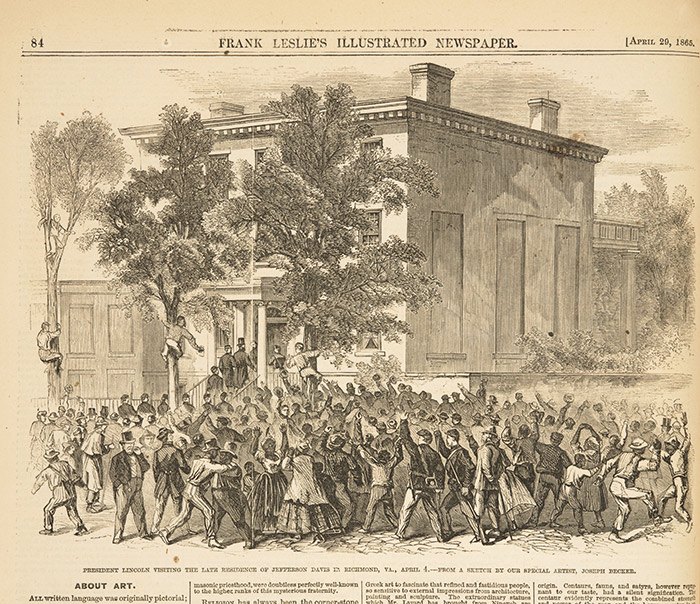

President Lincoln visiting the former residence of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, in Richmond, Virginia, on April 4, 1865. Wood engraving from a sketch by Joseph Becker. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 29, 1865. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

With the arrival of April, we begin the final countdown of Civil War Sesquicentennial commemorations. In short order, we will mark the 150th anniversaries of Appomattox (April 9), the shooting of Abraham Lincoln in Ford’s Theatre (April 14), and the death of the president (April 15).

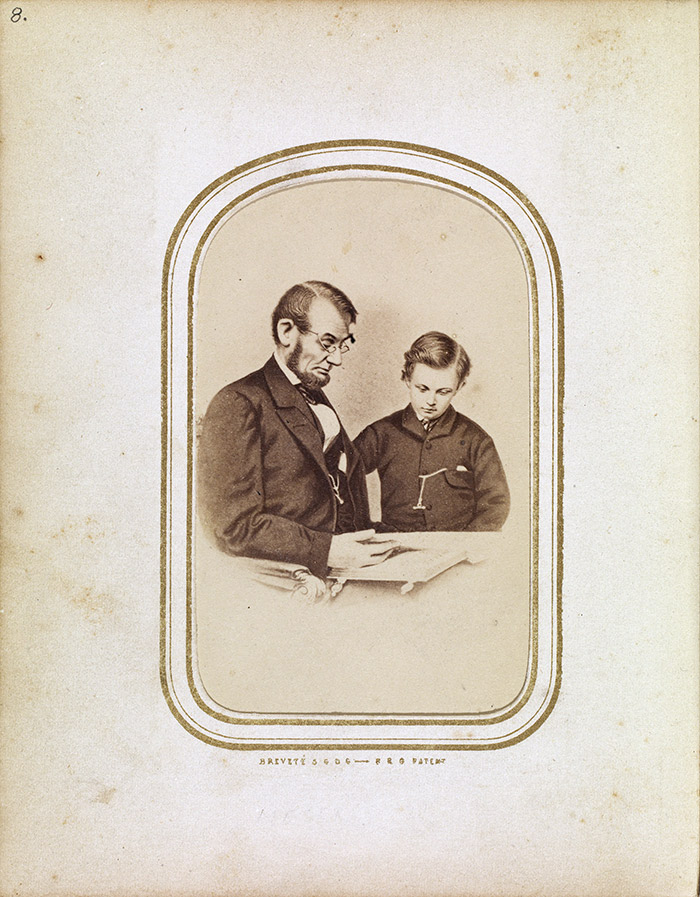

But don’t let April 4 go by without commemorating one of the most remarkable days of Lincoln’s presidency, his safe stroll through a conquered Richmond with his 12-year-old son Tad at his side. After Lincoln was shot in Ford’s Theatre on Good Friday, journalists would look back at Lincoln’s triumphal but humble march through the Confederate capital as the Union savior’s Palm Sunday: Lincoln entered Richmond just as Jesus had entered Jerusalem, praised and jostled by the poorest residents (the black slaves in Lincoln’s case) and destined soon for martyrdom. Lincoln ended the walk in Union Army headquarters, where he sat down quietly to drink a glass of water in a building that, just the day before, had been the Confederate White House of Jefferson Davis. Only after his assassination on April 14 would journalists and historians marvel at how Lincoln had tempted fate by risking his life in the heart of an embittered Dixie.

President Lincoln riding through Richmond, Virginia, on April 4, 1865. Wood engraving from a sketch by Joseph Becker. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 22, 1865. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

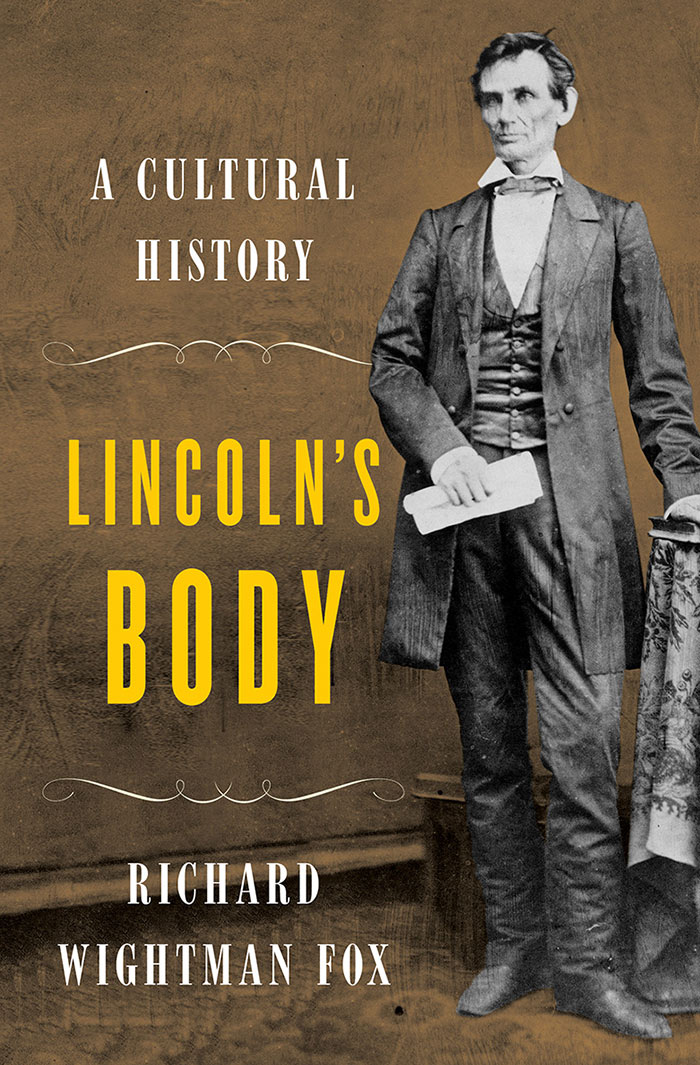

Historian Richard Wightman Fox, author of the new book Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History (W. W. Norton & Co., 2015), wonders why such a dramatic moment has become a mere footnote to most Americans.

“Until the early 20th century, the Richmond walk was an iconic episode in Lincoln’s life, but it’s largely unknown today,” said Fox, professor of history at the University of Southern California.

Fox will talk about his book on April 23 in Rothenberg Hall—part of the new Steven S. Koblik Education and Visitor Center—in a public lecture titled “What We’ve Forgotten about Lincoln’s Body, and What We’ve Never Known.”

In his book Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History, cultural historian Richard Wightman Fox explains how Lincoln’s body fascinated Americans throughout his life and even after his death.

It’s fitting that Fox will be among the first lecturers to inaugurate the new facility, which opens on April 4, 2015. Six years ago, on April 3, 2009, Fox delivered a memorable talk in the old facility, Friends’ Hall. That presentation, “Striding Toward Assassination,” focused on the Richmond walk and took place late in the afternoon of the first full day of a Civil War conference that marked the bicentennial year of Lincoln’s birth: “A Lincoln for the 21st Century.”

Fox drew attention to two additional anniversaries during his talk. First, he discussed the circumstances surrounding the Richmond walk, which, in 2009—Fox couldn’t help noting—had occurred seven score and four years ago. Lincoln’s respite in the Confederate White House had taken on apocryphal dimensions over the years, and Fox recounted his quest to find contemporary accounts of the episode.

Fox finished with a story about a speech that had taken place the night before the Richmond walk, at a Chicago rally celebrating the Confederate evacuation of Richmond, in which the speaker, Edwin Channing Larned, told the cheering crowd that he “fancied Lincoln sitting in Davis’ armchair in Richmond telling stories.”

As Fox came to the conclusion of his talk, it was well past 5 p.m. in San Marino, or 7 p.m. in Chicago—that is, it was the anniversary, down to the minute, of the Chicago gathering of 1865.

Inspired by this coincidence of timing, Fox asked the audience to join him in a rendition of “Battle Cry of Freedom,” one of the popular war songs belted out by the crowd in Chicago exactly 194 years earlier. With a photocopy of the lyrics as printed at the start of James McPherson’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book Battle Cry of Freedom, Fox cleared his throat and began singing what now seems like a final coda to the old Friends’ Hall:

We will welcome to our numbers the loyal, true and brave,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

And although they may be poor, not a man shall be a slave,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

Then a chorus of historians and audience members joined in—James McPherson among them:

The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the traitors, up with the stars;

While we rally round the flag, boys, we rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad Lincoln looking at a photograph album in photographer Mathew Brady’s gallery, Washington, D.C., Feb. 9, 1864. Photograph by Anthony Berger. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can commemorate the anniversary of the Richmond walk on April 4 by strolling through the newly opened Steven S. Koblik Education and Visitor Center on your way to the Library West Hall to view the exhibition “The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery,” which remains open until April 20. Richard Fox’s lecture on April 23 in Rothenberg Hall is free and open to the public; register online or call 800-838-3006.

Matt Stevens is the former editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine. He is now managing editor at the USC Rossier School of Education.