The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A Usable Past

Posted on Tue., Nov. 19, 2013 by

Monument to the 533-147th Pennsylvania Infantry at Little Round Top, site of an unsuccessful assault by Confederates on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. This photo is from a book published by the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission, The Location Of The Monuments and Tablets On The Battlefield Of Gettysburg, 1898.

In his address at the dedication of the Gettysburg National Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln evoked the memory of 1776. Few, if any, in the audience had been alive at the time of the American Revolution, but Lincoln knew the power of that Glorious Cause in the imaginations of most Americans.

Now, 150 years after that speech, how do Americans remember the Civil War?

That was the question posed by historian Joan Waugh in a recent lecture at The Huntington. Waugh is professor of history at UCLA and author most recently of U. S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (University of North Carolina Press, 2009). She has helped organize all five of the Civil War conferences held at The Huntington since 1999; she is currently planning another, on “The End of the War,” to take place in the fall of 2015. This year she is the Rogers Distinguished Fellow in 19th-Century American History at The Huntington.

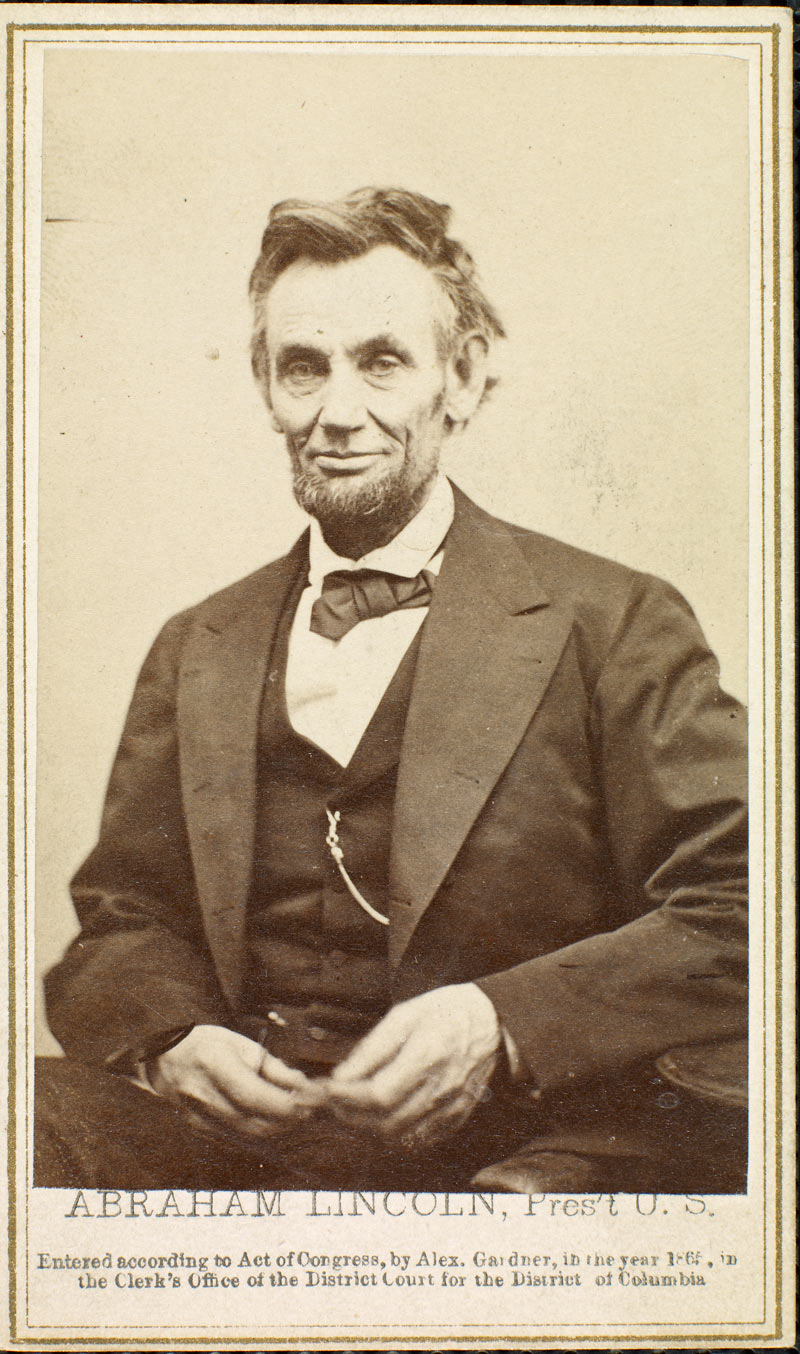

Portrait of Lincoln by Alexander Gardner (1821–1882), taken on April 10, 1865. This carte de visite photograph is on display.

In her talk—titled “1863 in History and Memory: Reflections on the Sesquicentennial”—she acknowledged that historians of the Civil War often find it difficult to separate history from historical memory.

“One very prominent historian,” she said, referring to Michael Kammen, author of Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (1991), “aptly summed up this idea by remarking that every generation ‘is manipulating the past to mold the present,’ sustaining what he called ‘a usable past to give shape and substance to national identity.’”

Waugh described the four memory traditions of the Civil War, the prisms with which Americans have come to understand this great conflict. The first is known as the Union Cause, the driving force of most Northern soldiers who were willing to give their lives to preserve the country, North and South. Theirs was a battle to save the republic, not to free the slaves.

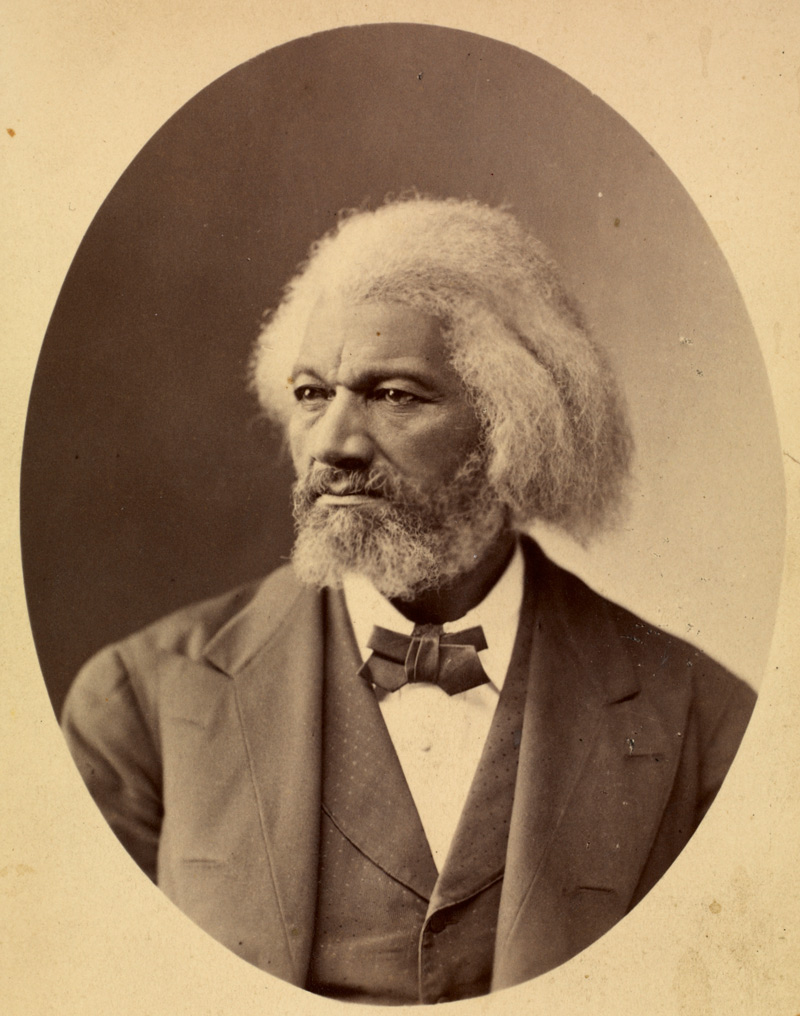

Contrasting to that tradition is the Emancipation Cause, best represented, says Waugh, by the voice of Frederick Douglass, who wrote, “No war but an Abolition war; no peace but an Abolition peace; liberty for all, chains for none.” (This tradition also fuels the words captured in Douglass’ own hand in a rare document now on view in the permanent exhibition “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times: Highlights from the Huntington Library.”)

Portrait of Frederick Douglass, also on display in "Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times."

The Reconciliation Cause emerged after the end of the war and was evoked to bring Northerners and Southerners together. Click here to listen to Waugh describe how the funeral of Ulysses S. Grant in 1885 represented the Reconciliation Cause by bringing the entire country together in mourning. Her comments are part of the ongoing online component of the 2012–13 photographs exhibition “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War.”

And the Lost Cause gives sympathy to the fatalism of the Confederate soldiers and glorified the war as a noble battle against impossible odds.

Waugh says that these traditions have changed over the decades. In fact, the arrival of the Sesquicentennial has brought us what she calls Reconciliation 2.0, a cause for the 21st century. How do you remember the Civil War?

For more on the commemorations, see Ronald C. White Jr.'s essay in the Los Angeles Times, "The Gettysburg Address: Much Noted and Long Remembered."

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.