The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Who Was Adah Isaacs Menken?

Posted on Thu., March 24, 2016 by

In a library collection as deep as the one at The Huntington, it’s not unusual for scholars to encounter items that propel them on new paths of research. That’s what happened recently to The Huntington’s 2015–16 Los Angeles Times Distinguished Fellow, Shirley R. Samuels, when she examined an extra-illustrated copy of a 19th-century book of poetry by actress Adah Isaacs Menken (1835–1868) and was surprised to see almost 100 images of Menken among its pages. Here are excerpts from a discussion with Samuels, a professor of English at Cornell University and the author of several books, including The Cambridge Companion to Abraham Lincoln and Reading the American Novel: 1780–1865.

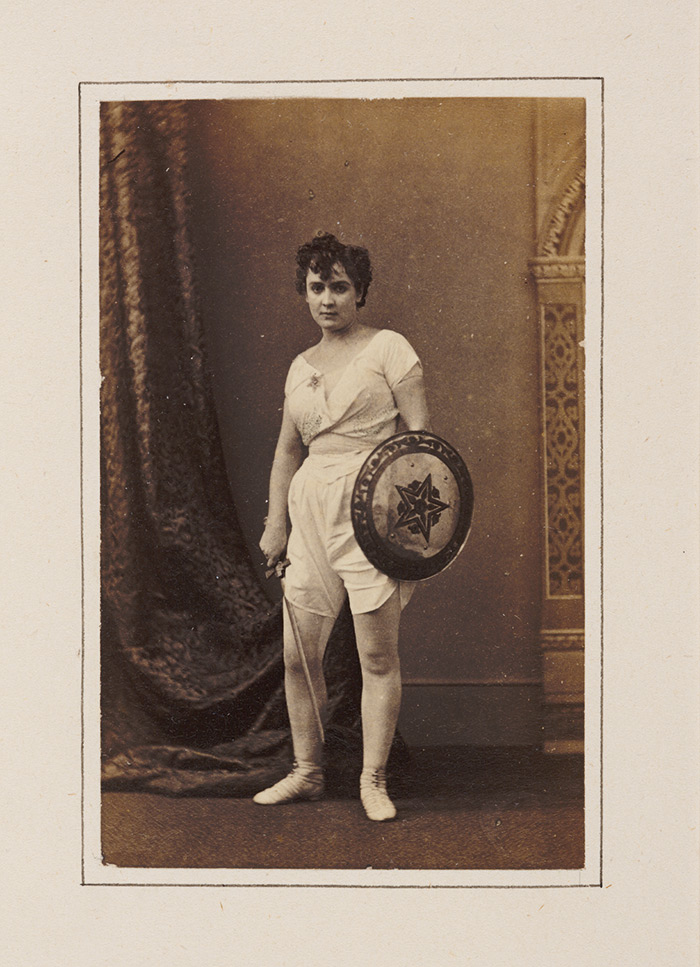

Adah Isaacs Menken as Leon, a Mexican slave, in John Brougham’s play Child of the Sun, ca. 1866. This is one of almost 100 images of Menken contained in The Huntington’s copy of Infelicia, an extra-illustrated book of Menken’s poetry. Photo by Napolean Sarony. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Q: Who was Adah Isaacs Menken?

A: In the 19th century, Menken was a household name. She was an actress with an outsized personality who had caused a sensation for her role in a play called Mazeppa, based on a poem by the English romantic poet Lord Byron. In the poem, a Ukranian gentleman, Mazeppa, has an affair with the young wife of a count. The count punishes Mazeppa by tying him naked to a horse and letting the horse run wild. In performances from New York to London, Menken played Mazeppa, riding a real horse on stage and wearing a body stocking that made her appear nude. The cross-dressing and nudity created a scandal, further amplified by tabloid news that proclaimed Menken had been married at least five times, possibly bigamously. Her last name came from her second husband, Alexander Isaac Menken, a musician from a prominent Jewish family. Menken would later claim she had been born Jewish, though questions remain about her true origins.

A more conventional portrait of Menken by Napolean Sarony. Date unknown. This image appeared opposite the first page of The Huntington’s copy of Menken’s Infelicia. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Q: Tell us about the book you found.

A: The book is called Infelicia (1868) and contains 31 of her poems. Menken wanted to be known as a writer, but most people recognized her as an actress. She was tied romantically to the writers Algernon Charles Swinburne and Alexandre Dumas (père), and she hobnobbed with many literary icons, including Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, and Charles Dickens—to whom she dedicated her book of poetry. But it was not until shortly after her tragically early death, at age 33 (probably of tuberculosis), that her poems were published.

Q: Infelicia was in print up until 1902. What is so unusual about The Huntington’s copy that you examined?

A: I came upon the book while doing research on several women leading lives that were outside of the typical roles for women at the time. Menken was one of them. A librarian directed me to this copy. Inserted into its pages were almost 100 images of Menken by celebrity photographer Napolean Sarony (1821–1896). They showed Menken as the barely dressed Mazeppa, as Lola Montez with a fan, and as a man in a sword-fighting duel. The photos were outlandish—but I was more intrigued by who had put them there.

In her role as Mazeppa, Menken performed in a flesh-colored costume that made her appear naked. Photo by Napolean Sarony. Date unknown. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Q: What’s your hunch about who included the photos, and how did you arrive at this conclusion?

A: I feel convinced that this was a loving tribute to Menken, created by celebrated theatrical entrepreneur Augustin Daly (1838–1899). The Huntington purchased the volume at a 1900 estate sale of Daly’s. Inside the volume was a letter to Daly in Menken’s hand. “I write in memory of one of the pleasantest incidents of my life—our old acquaintanceship,” Menken wrote. I also learned that Daly was known to have collected photographs of famous actors, many of them taken by the same Sarony. Menken’s letter implores Daly to write to her. I have no way of knowing whether he acted on her invitation.

Q: What about her poems? Were they as scandalous as her personality?

A: The poems in Infelicia (meaning “unhappiness”) are full of passion and carefully staged. Her yearning for an identity commensurate with her personality appears, for example, in the poem “Judith,” recounting the Bible story of the Book of Judith, in which the beautiful widow seduces and then beheads the Assyrian general Holofernes, saving Judith’s city of Bethulia. In Menken’s poem, the speaker appears with “the strong throat all hot and reeking with blood” and ends by declaring, “Oh forget not that I am Judith/And I know where sleeps Holofernes.” Clearly, this voice needed to be heard.

Shirley Samuels holds the letter that Menken wrote to theater entrepreneur Augustin Daly from her home, which she called “Bleak House,” a reference to the 1853 novel by Charles Dickens. Menken dedicated her book of poems, Infelicia, to Dickens. Photo by Kate Lain. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

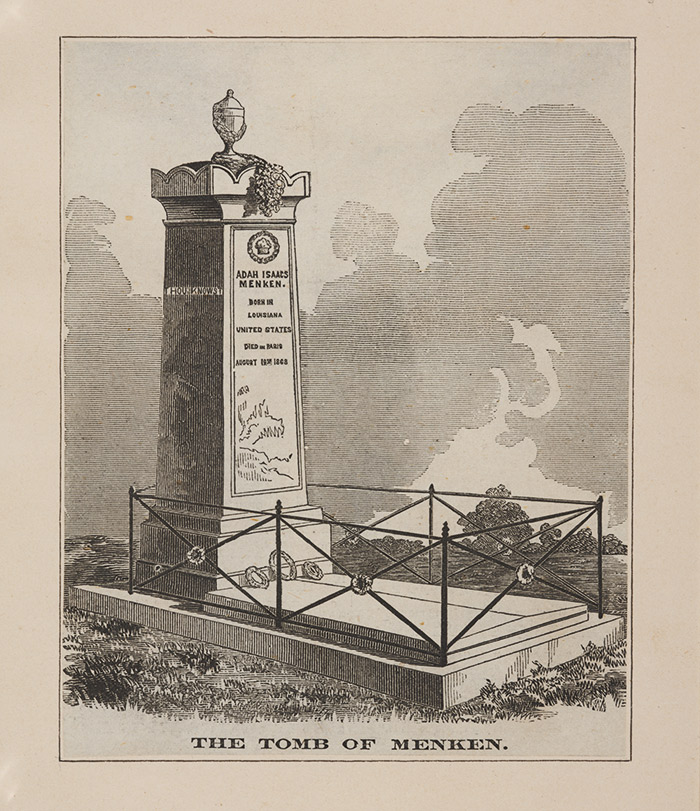

Q: The last image included in The Huntington’s copy of Infelicia was an engraving of Menken’s tomb. What do you make of it?

A: I believe the image is a testament to this tragic young life cut short. In the last years of her life, Menken had been living and performing in London and Paris. She fell ill while in London, ending her acting career. She moved back to Paris and worked on preparing her poems for publication. She didn’t live long enough to see the book in print. She died in Paris on August 10, 1868, and was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery. Infelicia was published several days later. On her tomb are the words “Thou Knowest.” They make me wish I knew even more about this complex, fascinating woman.

Engraving of Menken’s tomb in Montparnasse Cemetery, with the inscription “Thou Knowest.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can read the Verso post “Reading the Aftermath of War” by Shirley Samuels here. You can download the lecture “Looking at Lincoln” by Shirley Samuels here or listen to it on iTunes U.

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.