The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Women Computing the Stars

Posted on Tue., Sept. 8, 2015 by

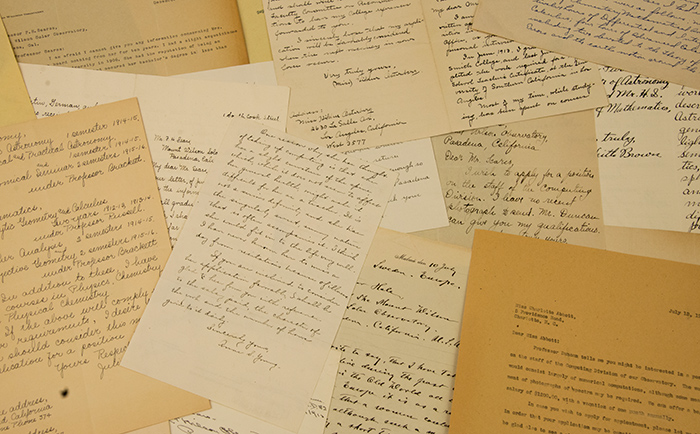

A selection of women’s application letters for computer positions among the papers of American astronomer Frederick Hanley Seares (1873–1964), the head of the computing division at the Pasadena office of the Mount Wilson Observatory from 1909 to 1940. Photo by Kate Lain.

A piece of women’s history lies deep in the underground stacks of the Huntington Library, among the papers of American astronomer Frederick Hanley Seares (1873–1964). Seares was the head of the computing division at the Pasadena office of the Mount Wilson Observatory from 1909 to 1940. His correspondence gives us a glimpse into a select group of women who found employment at an institution known for its pioneering ideas and unparalleled views of the heavens.

The opening decades of the 20th century saw the blossoming of new ideas about astronomy, new uses for computing, and new opportunities for women. The word “computer” did not always refer to the massive mainframes of yesterday or the feather-light tablets of today. Rather, computers were human beings who performed scientific computations.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these human computers worked in observatories, where the study of astronomy required the extensive use of advanced mathematics and an enormous volume of calculations. At Mount Wilson, employees measured the positions and magnitudes of stars on photographic plates, calculated the position and intensity of spectrum lines, and counted sunspots, determining their intensity and movement. These workers had to have the right skills and enough patience to endure long hours of tedium mixed with very close attention to detail. Most of these early “human computers” were women.

Unidentified women and men standing outside the Mount Wilson Observatory’s Pasadena office, where women computers made the calculations necessary to answer some of the most profound questions in the field of astronomy during the early part of the 20th century. Detail from a photo taken on April 14, 1917, by an unknown photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Among the Seares papers are dozens of women’s application letters for computer positions. Their credentials are impressive:

“I have a doctor of philosophy in Astrophysics from the University of Michigan, and I held a fellowship in Astronomy at the Detroit Observatory.”

“I have a PhD in astronomy from the University of California.”

“I measured seismograms.”

“I graduated at Berkeley as an astronomy major . . . and have [completed] graduate work in physics.”

They also came highly recommended by their former professors. “She is an excellent mathematician, quick and accurate, very neat and orderly, and she thinks,” wrote one. “She possesses high intelligence and distinctly scientific attitude, great carefulness and sincere faithfulness,” wrote another.

Finding a niche in the world of science and technology in those days was not easy for women—not even for the highly qualified. It’s important to note that some of the earlier computer applicants could not even vote (a right granted in 1920), let alone hold an equal position in the world of science. It’s also telling that the letters of recommendation came predominantly from male professors.

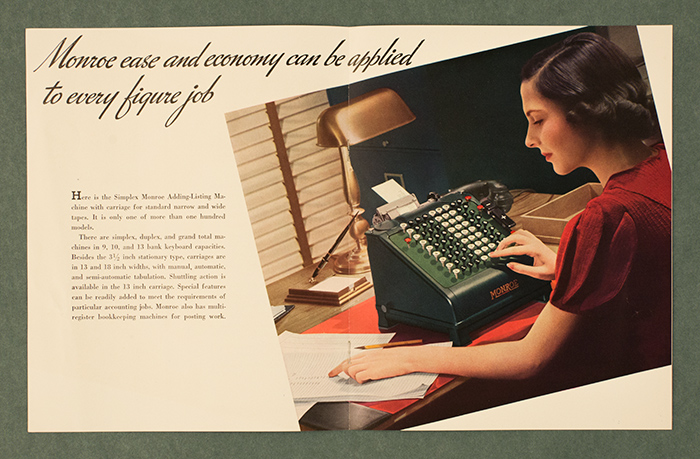

A 1920s advertisement for a calculating machine. Ever more sophisticated machines eventually replaced human computers. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The need for human computers, however, opened doors for women. Computing was generally thought of as women’s work, and computers were assumed to be female. Mathematicians would approximate the time needed to complete calculations in “girl-years” and describe a unit of machine labor as equal to one “kilo-girl.” Applicants’ letters stressed attention to detail and patience—believed to be ideal qualities of a “computer.”

This is not to say that male and female applicants received equal evaluation. The professor who recommended Doris Wood praised her “rare tact and good sense” and saw her as “a fine example of kindly, noble womanhood.” Another woman was described as displaying a “refinement of manipulation in the laboratory,” but did not have “the same initiative which we find in our best trained men.” Women were compared to men but evaluated as women. Seares himself made this request: “It would help me, however, somewhat if you would kindly send me a photograph of yourself.” Male applicants received no such requests.

Yet the Seares papers clearly demonstrate the emerging role of women in science. These human computers became so valuable that, in many cases, they shared authorship with astronomers in published works. Louise Ware, for example, began work at the observatory in 1907 and was credited in 1926 as one of four authors of the Revised Rowland Table of Solar Lines, a catalog of spectral lines indicating the presence of particular elements in the sun.

The need for human computers gradually declined as new mechanical calculating machines and later computers became available; by the 1960s, very few human computers were employed. But that does not lessen the contributions made by women working in the early days at the Mount Wilson—making the calculations necessary to answer some of our most profound questions about the heavens.

Related content on Verso:

Einstein and the Astronomers (March 13, 2015)

Hubble and Copernicus (Nov. 8, 2012)

Catherine Wehrey is the Dibner Reader Services Coordinator for Reference and Instruction at The Huntington.