The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Walt Whitman’s Bedside Manners

Posted on Tue., Dec. 17, 2019 by

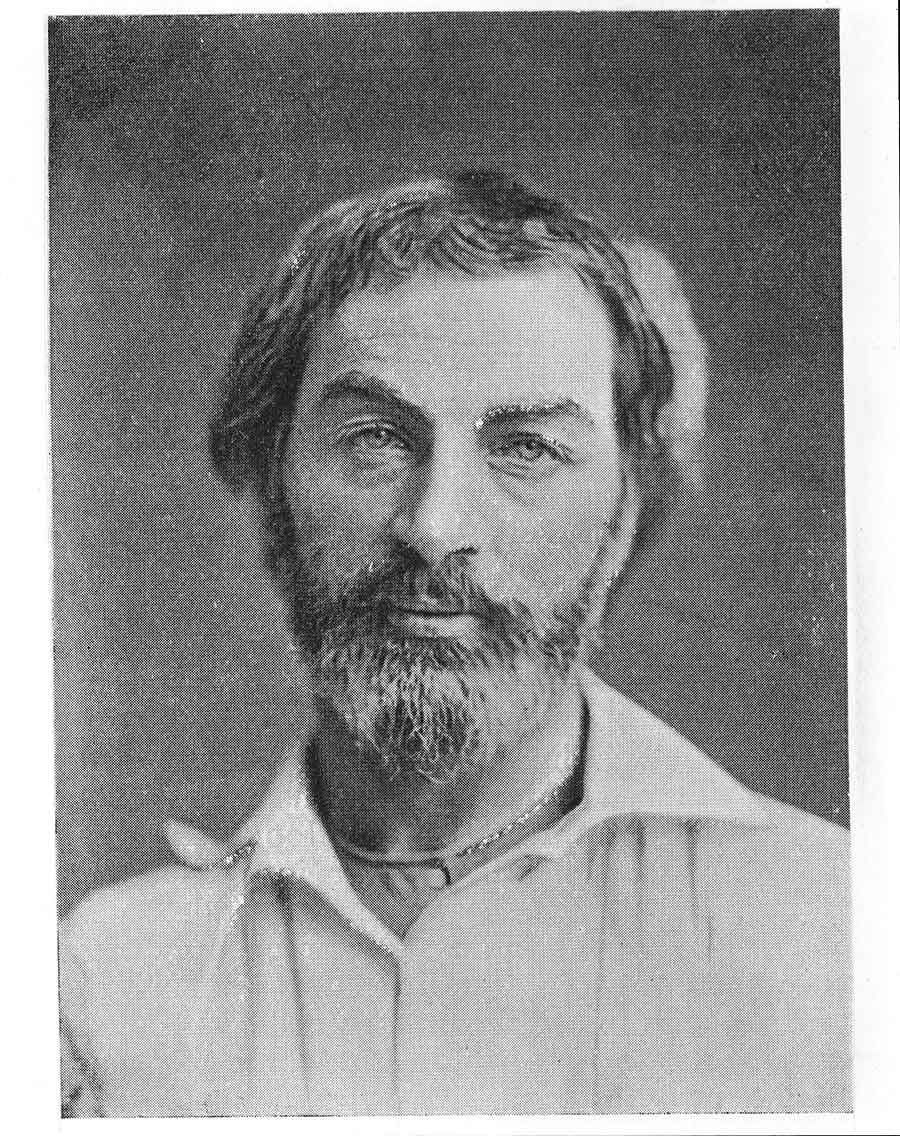

Portrait of the American poet, editor, and journalist Walt Whitman (1819–1892) in Edith Sprague Taft’s Scrapbook of American Literature, 1855. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington's 2019 Centennial Celebration also marks the 200th birth year of Walt Whitman (1819–1892), the Good Gray Poet and a collecting interest of Henry E. Huntington. Walt Whitman represented two fields the founder especially valued: American literature and the American Civil War.

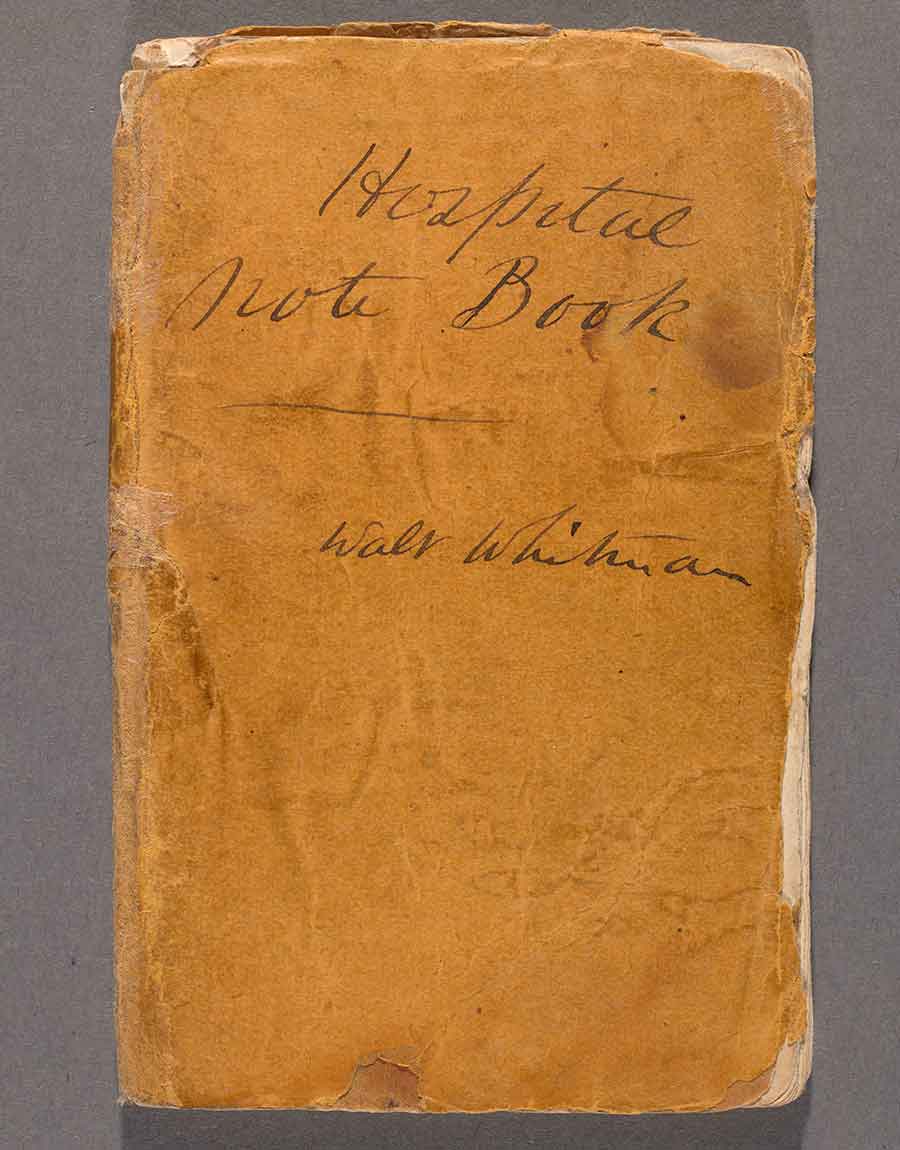

Among the gems in The Huntington’s collection is a little yellow-brown notebook, measuring 2 1/2 by 4 inches, made to carry in a vest pocket. It has 28 thin leaves, bound by a pink string. On its cover, an autograph ink inscription reads “Hospital Note Book” above a small horizontal line, and below the line, “Walt Whitman.”

A pocket-size notebook kept by Whitman in 1863 during his service as a volunteer nurse in the Civil War. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington’s pocket notebook of “impromptu jottings” is one of perhaps 40 “soil’d and creased little livraisons” the poet carried during the Civil War, as he later wrote in Memoranda During the War (1875), his rich and moving account of volunteer visits to the sick and wounded in the army hospitals of Washington, D.C., from December 1862 through 1865.

These volunteer visits began spontaneously in Fredericksburg, Virginia, after Whitman read in a Brooklyn newspaper that his younger brother George had been wounded in the battle there. Whitman left Brooklyn immediately to locate George among the Fredericksburg wounded, and once he found him, alive and well, Whitman never looked back. He had discovered his mission and his calling.

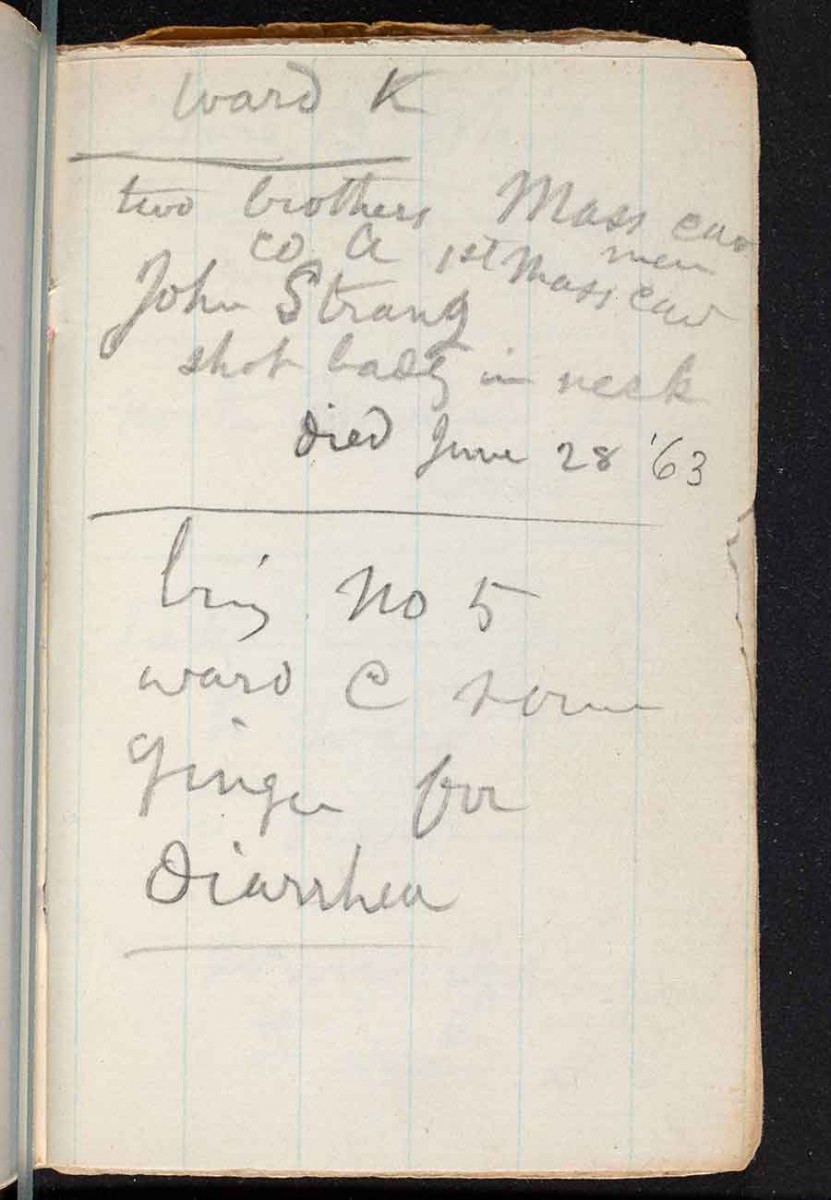

Page 13 of Whitman’s hospital notebook: “ward K / two brothers Mass cav men / co A 1st Mass cav / John Strang / shot badly in neck / died June 28 ’63 / bring no 5 / ward C some / ginger for / diarrhea.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

“Altho it is a mere trifle in appearance,” admitted a Publishers Weekly auction advertisement for the hospital notebook, “it is pretty sure not to bring a trifling price.” Huntington paid $435 for the notebook on March 17, 1920, which would be roughly equivalent to $6,000 today.

Whitman claimed he jotted in his notebooks “to refresh my memory of names and circumstances, and what was specially wanted” by sick and wounded soldiers. The delicate leaves of The Huntington’s notebook show his method during 1863: “ward K / two brothers Mass cav men / co A 1st Mass cav / John Strang / shot badly in neck / died June 28 ’63 / bring no 5 / ward C some / ginger for / diarrhea.”

There were four Strangs in the First Massachusetts Cavalry: Cyrus, Gabriel, Jesse, and John. John A. Strang was a private, probably wounded in one of the Virginia cavalry battles of June 1863—Kelly’s Ford, Brandy Station, Stevensburg, Aldie, Upperville—all preludes to the Gettysburg campaign, in which the First Massachusetts also fought. (The battle of Brandy Station remains the largest cavalry battle fought in North America.)

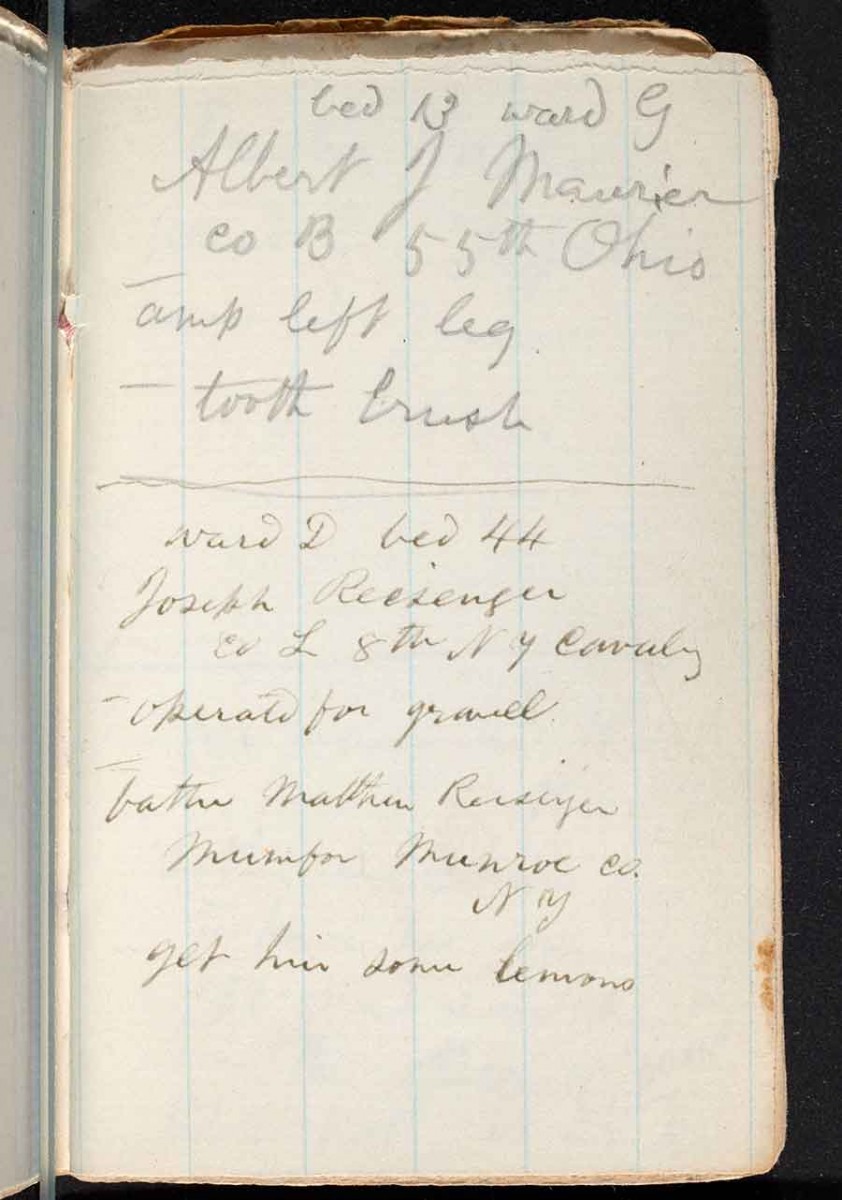

Top of page 19 in Whitman’s hospital notebook: “bed 13 ward G / Albert J Maurier / co B 55th Ohio / amp left leg / tooth brush.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Usually Whitman jotted the ward of a particular hospital, the bed number, a soldier’s company and regiment, and often a particular thing he wanted. Sometimes the results are jolting: “bed 13 ward G / Albert J Maurier / co B 55th Ohio / amp left leg / tooth brush.” Albert was a private, too.

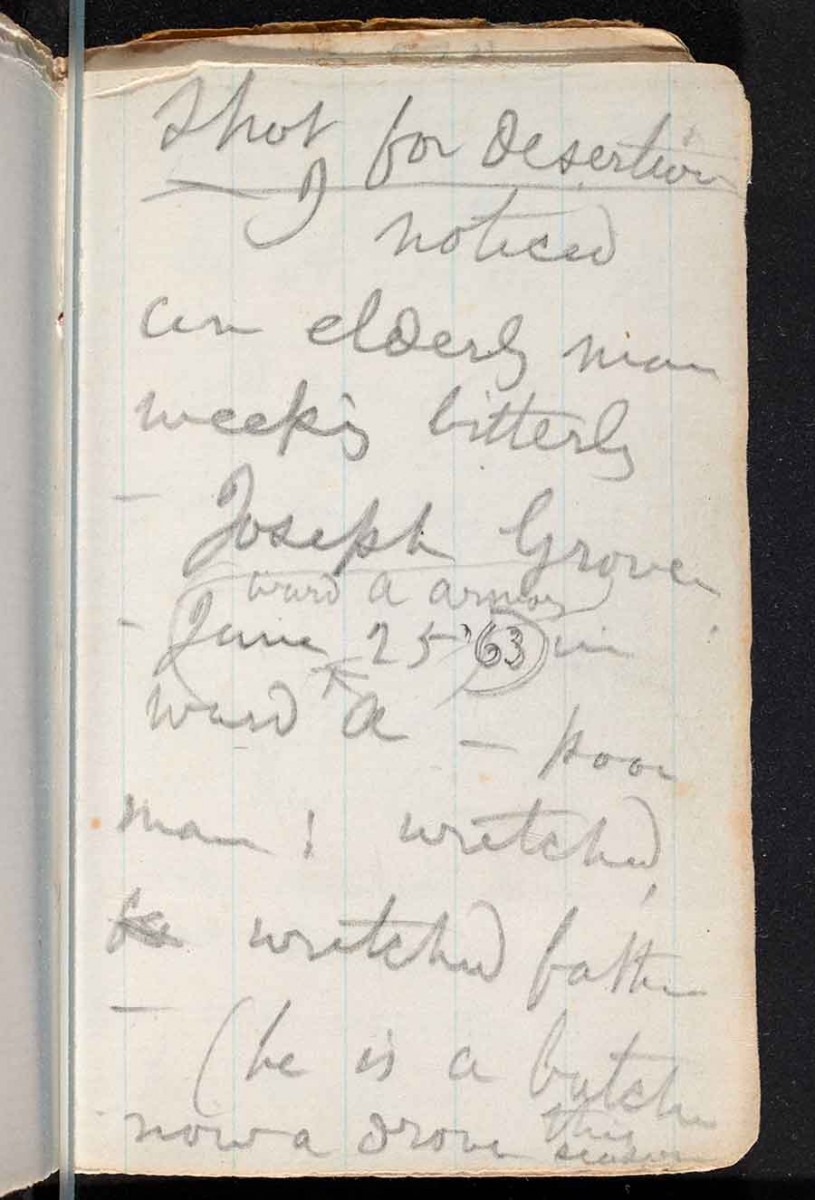

Then there was William Butler Grover, Co. A, 46th Pennyslvania. “I noticed / an elderly man / weeping bitterly / Joseph Grover / . . . June 25, ’63 / . . . – poor / man! wretched / wretched father.” The front page of the New York Heraldfor this date, a Thursday, reported the execution of Joseph’s son, for desertion, the previous Friday, June 19, “at the camp / of the 12th Army Corps” in Leesburg, Virginia, Whitman noted.

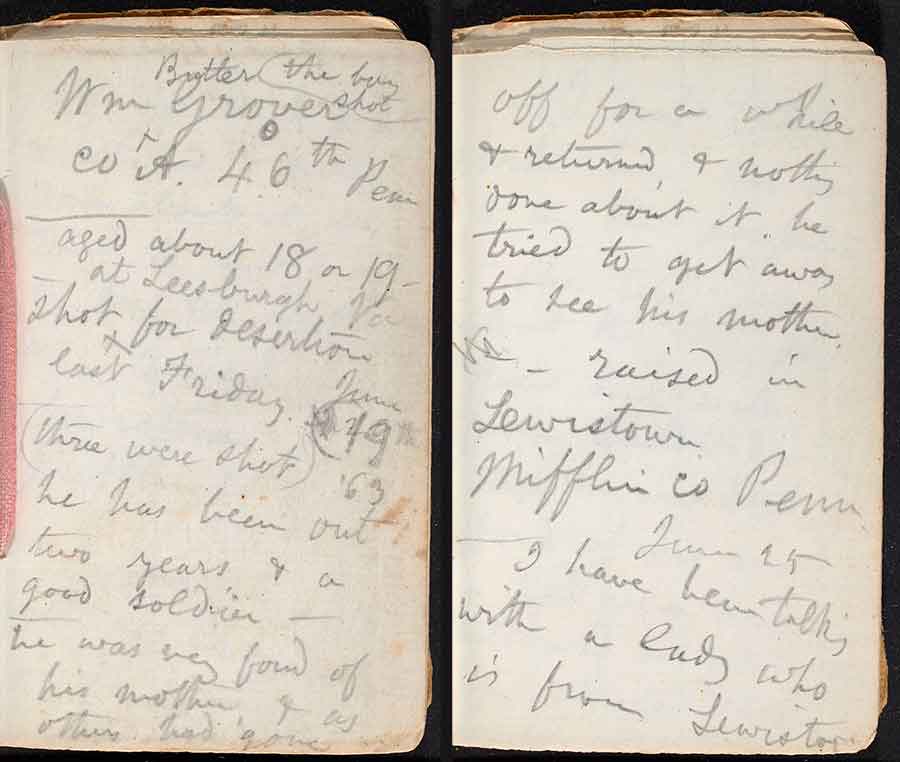

William Grover, “aged about 18 or 19” and “a good looking / dark haired / fellow,” had “been out / two years + a / good soldier – / he was very fond of / his mother + as / others had gone / off for a while / + returned + nothing / done about it. / he tried to get away / to see his mother – raised in / Lewistown / Mifflin co Penn.”

On page 27 of his hospital notebook, Whitman wrote of Joseph Grover, whose teenage son, William Grover, a Union soldier, had been executed for desertion: “I noticed / an elderly man / weeping bitterly / Joseph Grover / . . . June 25, ’63 / . . . – poor / man! wretched / wretched father.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Lewistown sits along the Juanita River, 50 miles northwest of Carlisle. On the same front page, the Herald boomed: “THE REBEL INVASION / Advance of the Enemy in Heavy Force into Pennsylvania / Intense Alarm Along the Border / The Rebels Within Six Miles of Carlisle / Expected Battle Near Carlisle To-Day.”

Two weeks after his execution, William Drover’s corps distinguished itself at Gettysburg in the defense of Culp’s Hill.

Looking back at his hospital service, Whitman estimated that he made 600 visits and spent time as a “sustainer of spirit” with between 80,000 and 100,000 soldiers from both sides. The emotional and physical demands of his hospital service cost him his health; he suffered his first stroke, which left him partially paralyzed, in 1873.

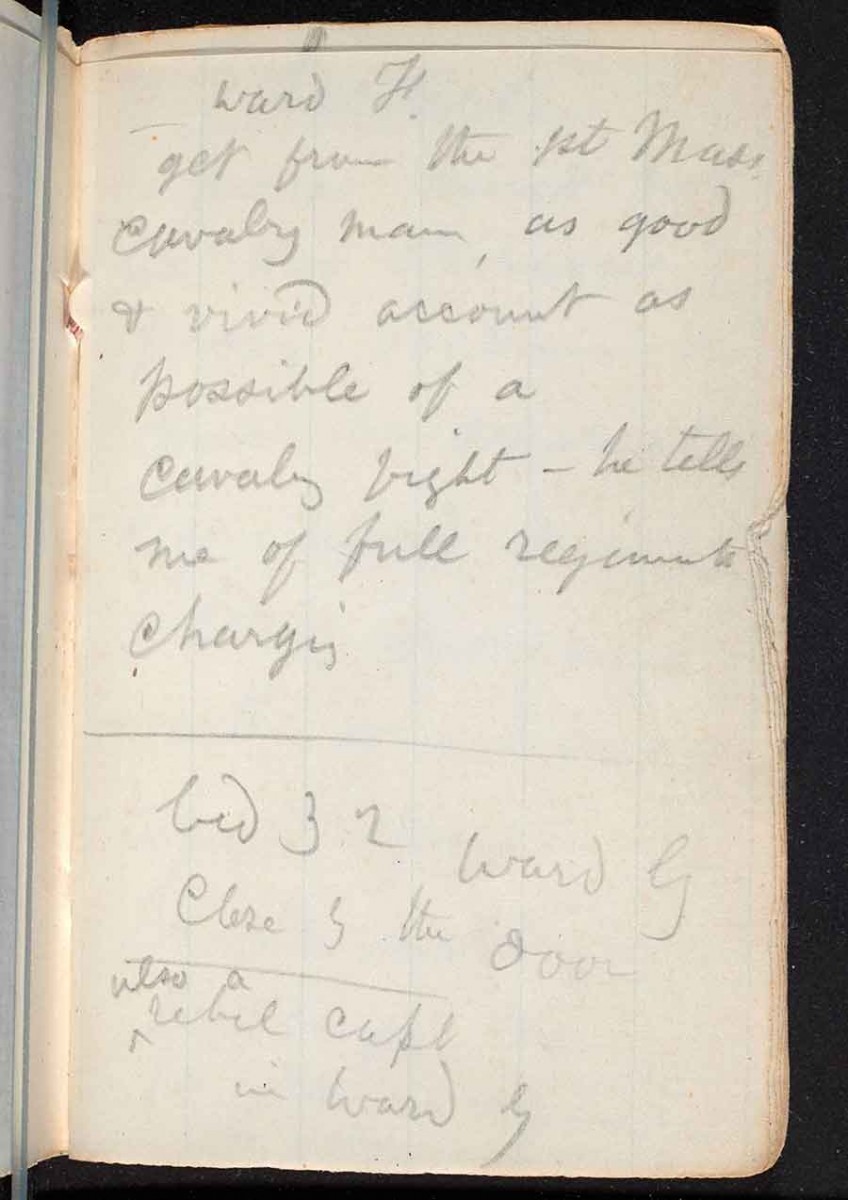

Although the cost was high, so were the rewards. Whitman formed several close attachments with men he visited and with their families. He also gathered material for his writing, both verse and prose. The Huntington’s hospital notebook gives us a revealing glimpse behind the scenes into Whitman’s writing method: “ward F / get from the 1st Mass. / cavalry man, as good / + vivid account as / possible of a / cavalry fight – he tells / me of full regiments / charging.”

On page 29 and 30 of his hospital notebook, Whitman wrote of the teenage Union soldier William Grover, who had been executed for desertion. Grover had “been out / two years + a / good soldier – / he was very fond of / his mother + as / others had gone / off for a while / + returned + nothing / done about it. / he tried to get away / to see his mother – raised in / Lewistown / Mifflin co Penn.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Soldiers Whitman visited were there to care for, there to write about, and there to pump for details of combat. In Memoranda During the War, he mixed firsthand observations with imaginative recreations of soldiers’ stories. Cavalrymen he saw riding through Washington, or camping around the city, particularly fascinated him, but only someone like the unnamed Massachusetts man could give details of these men in action.

In Memoranda During the War, Whitman turned such details into a section he titled “A Glimpse of War’s Hell-Scenes”: “At this instant a force of our cavalry, who had been following the train at some interval, charged suddenly upon the Secesh captors, who proceeded at once to make the best escape they could.”

Near Upperville, Virginia, these Union cavalrymen summarily executed the Confederates for atrocities committed against their captured comrades. Though only 50 miles from Washington, Upperville meant fighting, and Whitman could know nothing of it without the men he met.

On page 7 of his hospital notebook, Whitman wrote: “ward F / get from the 1st Mass. / cavalry man, as good / + vivid account as / possible of a / cavalry fight – he tells / me of full regiments / charging.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

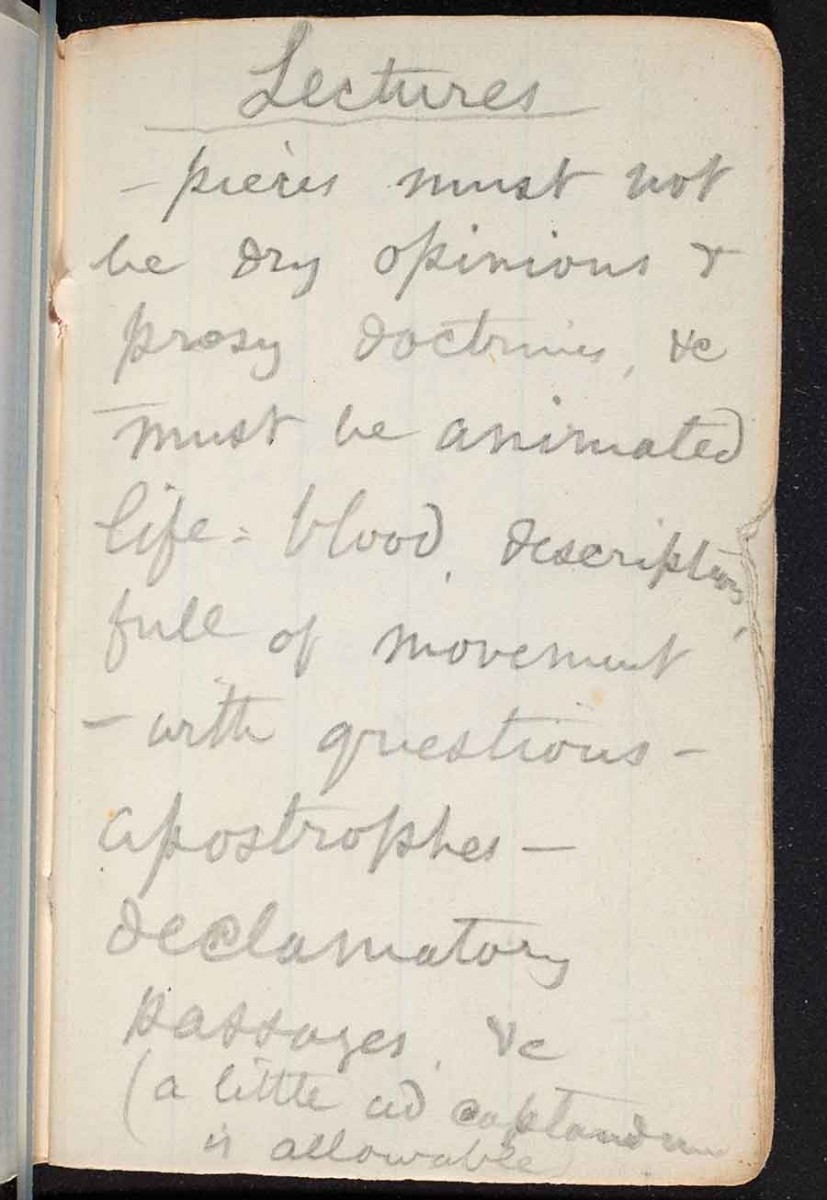

One leaf in The Huntington’s notebook shows Whitman mulling how to turn his hospital visits not into writing but into lecturing: “Lectures / —pieces must not / be dry opinions + / prosy doctrines, &c / must be animated / life-blood descriptions, / full of movement / —with questions— / apostrophes— / declamatory / passages, &c.”

At the bottom of the same leaf, after the list of ingredients for good lectures, the poet scrawled, “(a little [two words illegible] / is allowable).” The first illegible word begins with “a,” and the second looks something like “captain.” Captain? Whitman’s famous poem “O Captain! My Captain!” was still two years in the future.

But a momentary lapse into sloppy handwriting is not the only challenge for anyone trying to decipher this page. Another is realizing that the illegible words are Latin ones, and coming from Walt Whitman, who loved the vernacular and published an essay called “Slang in America,” Latin is a surprise.

“Lectures / —pieces must not / be dry opinions + / prosy doctrines, &c / must be animated / life-blood descriptions, / full of movement / —with questions— / apostrophes— / declamatory / passages, &c. / (a little ad captandum / is allowable.” The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Whitman’s hard-to-read words are “ad captandum,” the first two words of the phrase ad captandum vulgus. It means “for catching the crowd” or “for captivating the masses.” In The Huntington’s hospital notebook, Whitman gave himself permission to write with the aim of catching and captivating us. The rest of the story is proof he succeeded.

The Whitman hospital notebook, which can be viewed online in the Huntington Digital Library, is a highlight of The Huntington’s small but important Whitman holdings, which include numerous drafts of poems and essays, some letters, and, in addition to the notebook, a small loose-leaf sheaf of notes from his time volunteering in Union hospitals during the Civil War.

For a look at a different Civil War treasure, visit the “Nineteen Nineteen” exhibition in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery . On display there through Jan. 20, 2020, are the manuscript books of William Tecumseh Sherman’s Memoirs (1875).

Stephen Cushman is Robert C. Taylor Professor of English at the University of Virginia and the 2019–20 Rogers Distinguished Fellow in 19th-Century American History at The Huntington. He will give a public lecture titled “The River Changes Course: Mark Twain’s Mississippi and His Civil War” on May 20, 2020, in Rothenberg Hall.