The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Robbery and Rats in 17th-Century Jamaica

Posted on Thu., May 5, 2016 by

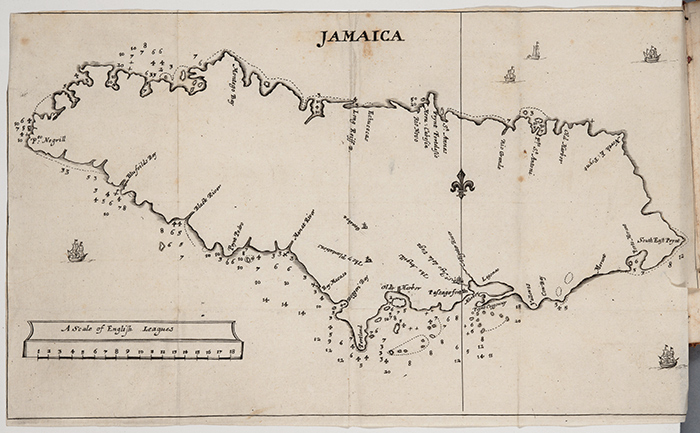

This beautiful color map of Jamaica dates from the early 1670s, after Jamaica had been divided into parishes. It was produced by John Seller. The inset table lists major planters and the major crops each produced. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Archival research involves thousands of tiny discoveries, while writing history requires putting those fragments together into a coherent whole. The process, often tedious, can occasionally be exhilarating. Every once in a great while a researcher discovers a gem. I had such an experience as I was researching the mid-17th-century English conquest of Jamaica—the subject of my next book. Among the William Blathwayt papers, I found a modest-looking sheet that revealed much about the challenges England faced in protecting the goods it stored on the island.

Sprinkled throughout The Huntington’s holdings are impressive early modern Caribbean materials that include rare books, manuscripts, and early maps. The particular document that caught my eye appears in the manuscript collection of one of the first English colonial administrators, William Blathwayt (1650–1717). Blathwayt was raised by his uncle Thomas Povey, a wealthy merchant and colonial official. Thomas Povey had secured a position in Jamaica for his brother Richard Povey as Commissary, which entailed receiving and distributing the food, clothing, shoes, and ammunition that England used to support its military campaign on the island. Thomas Povey must have acquired this document from his brother, and then it fell into Blathwayt’s hands when he settled his uncle’s estate.

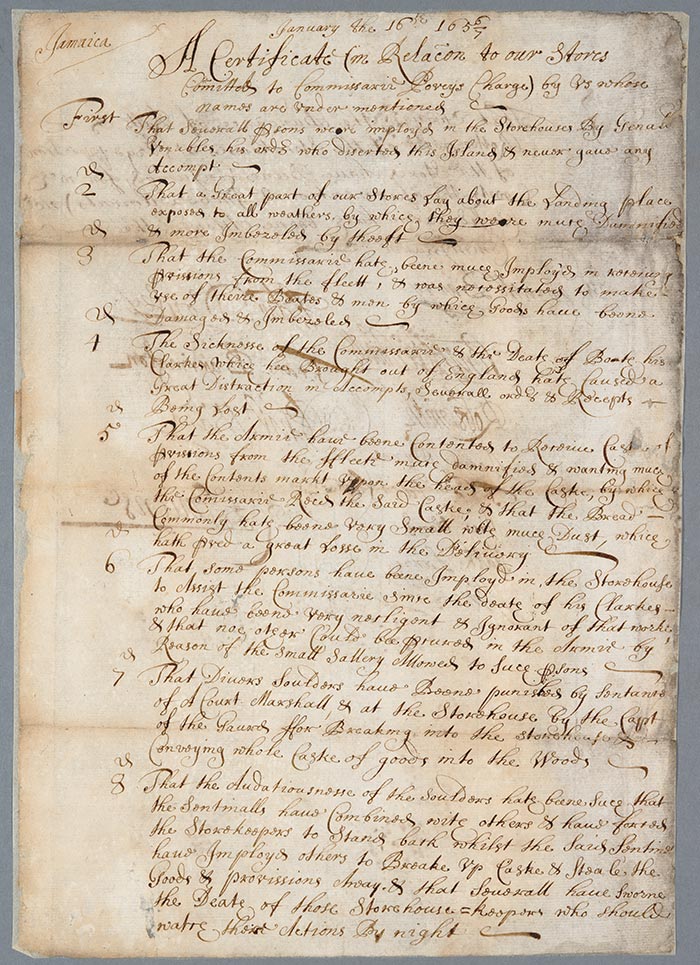

A Certificate (in Relation to our Stores Committed to Commissarie Povey's Charge), Jan. 16, 1656/7, recto. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Looks can be deceiving. Despite its unassuming appearance, the 17th-century document communicates a host of problems during the period that I’m studying. Entitled “A Certificate (in Relation to our Stores Committed to Commissarie Povey's Charge),” it tries to provide legal cover to Richard Povey, who was responsible for managing and protecting England’s storehouse on the island.

Items disappeared from the Jamaica storehouse on a regular basis, and for an astounding number of reasons. Rats—originally and inadvertently brought from Europe but, by the time of this document’s creation, endemic to the island—ate much of the food and damaged other items. That wasn’t the only problem. The building itself rotted in the wet climate; wooden casks sustained damage, ruining the items contained within. Some things disappeared as they were being transferred from ship to shore in small boats.

More dramatically, the “Certificate” describes how audacious soldiers assigned to guard the storehouse conspired with others to coerce the storekeepers to “stand back” while men broke open the casks and stole “Goods & provisions.” They threatened the storekeepers and admonished them to ignore these incursions. Parties of soldiers would make off with their ill-gotten gains, stealing into the nearby woods with food and quite possibly alcohol. The English soldiers on Jamaica, detained there against their will and without pay, suffered terribly at times from short rations. One can only imagine that, if the storehouse was full, they took matters into their own hands. This remarkable document briefly and succinctly conveys a great deal about these dynamics.

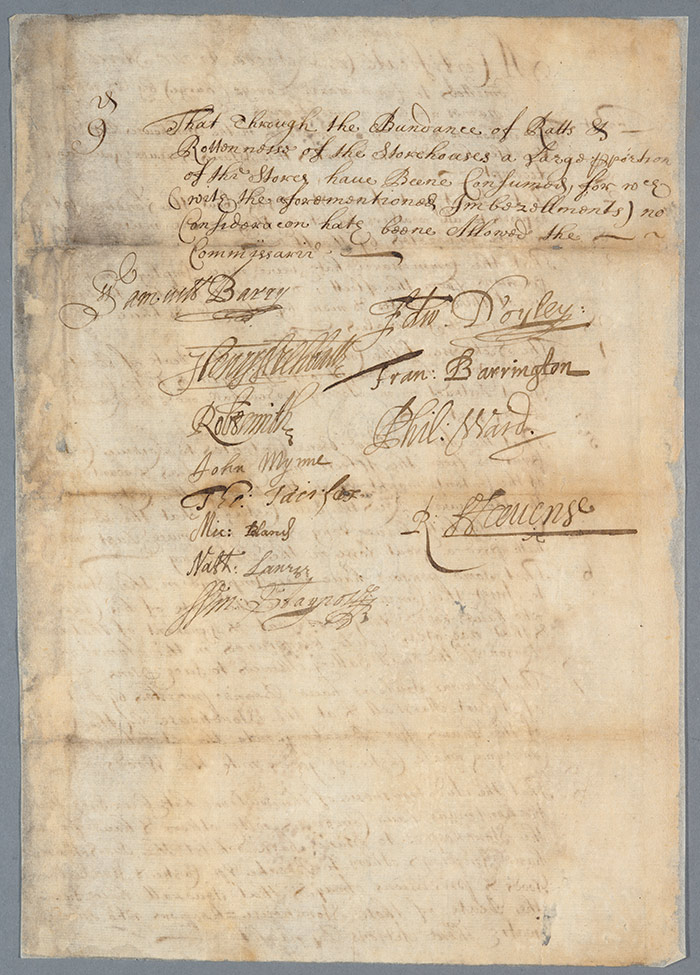

A Certificate (in Relation to our Stores Committed to Commissarie Povey's Charge), Jan. 16, 1656/7, verso. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The text itself covers most of a single sheet that is now yellowed by age, with faded ink. It bears a somewhat confusing date, “Jan 16, 1656/7.” The New Year began on March 25 in England, which used an older calendar until finally joining the rest of Europe in a 1754 reform, while the year began on January 1 in most other European countries. As a result, English documents would sometimes include both years to account for the days falling between the two. (Writers sometimes omitted this practice or used it only for the days in the dual month of March, however, which presents a possible pitfall for unwary researchers.) Following the body of the text, which is organized into bullet points, a dozen signatures appear, beginning with that of Edward D’oyley, who governed Jamaica for most of its first seven years under English rule. The signatures corroborate that this item is the original, not a contemporary copy, and they include the only surviving signatures of some of the men who participated in the colonization of early English Jamaica.

The Huntington acquired the William Blathwayt papers in 1924. Almost a century later, I was able to study this simple, faded document and discover a wealth of information about how rats, embezzlement, theft, and other problems impeded the flow of goods into and out of a storehouse in Jamaica more than three centuries ago.

This is the earliest known map from English Jamaica. It appeared in Jamaica Viewed (1661), a book by Edmund Hickeringill. The map is probably based on one that was produced by order of Edward D’oyley, lead signatory of “A Certificate.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can view John Seller's color map of Jamaica in more detail at the Huntington Digital Library.

You can download Carla Pestana’s Distinguished Fellow lecture, “Oliver Cromwell’s Consolation Prize? The English Conquest of Jamaica” here or listen to it on iTunes.

Carla Pestana, the 2015–16 Robert C. Ritchie Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington, is professor of history and Joyce Appleby Endowed Chair of America and the World at UCLA. Among her recent books are Protestant Empire: Religion and the Making of the British Atlantic World and The English Atlantic in an Age of Revolution, 1640-1661 .