Contemplating the impact of Blue Boy's departure from England

Kevin Salatino, Hannah and Russel Kully Director of the Art Collections at The Huntington, with Thomas Gainsborough's Blue Boy (1770). Photograph by Kate Lain.

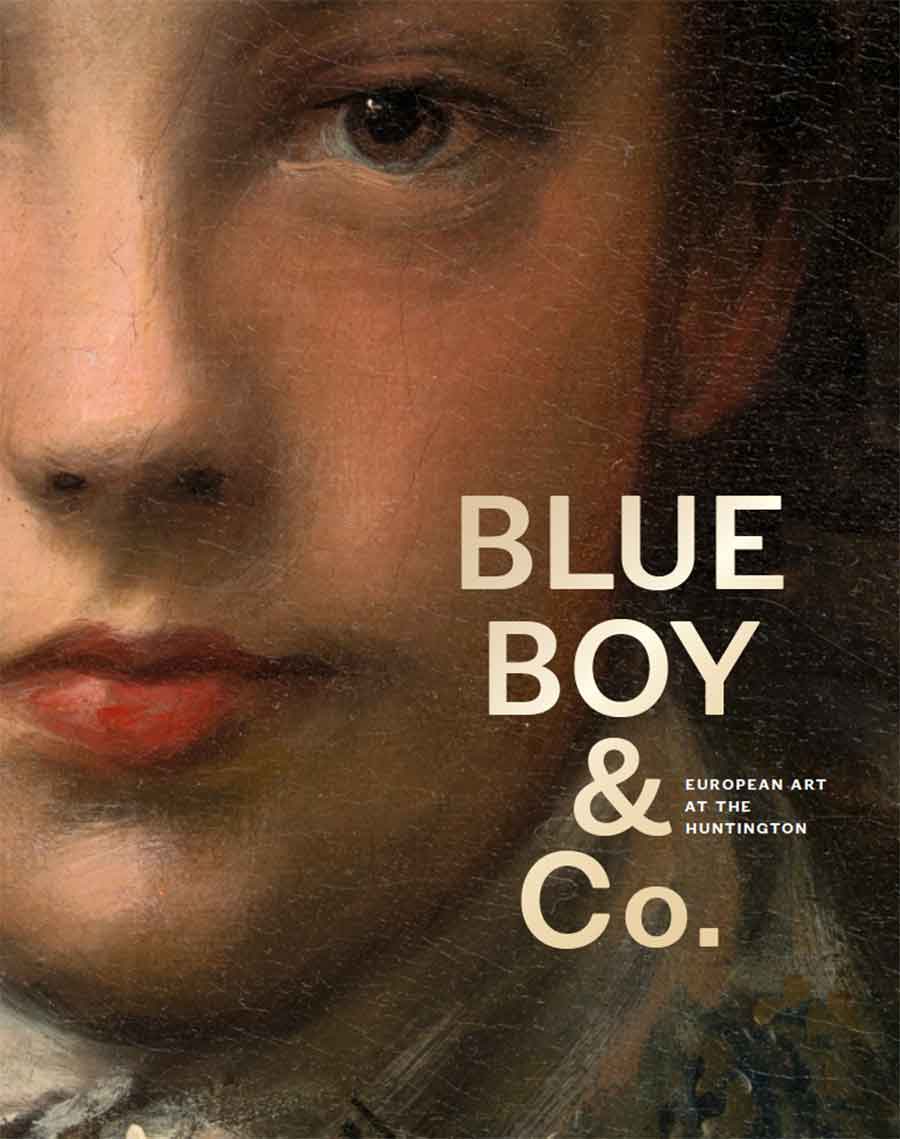

This fall, Huntington art curators Catherine Hess and Melinda McCurdy unveil Blue Boy & Co., a 179-page book highlighting the richness and diversity of The Huntington's European collection. The book opens with a foreword by Kevin Salatino, Hannah and Russel Kully Director of the Art Collections, who shares how the departure of Thomas Gainsborough's Blue Boy from England to Southern California in the 1920s stirred the emotions of the British public not long after the end of World War I. What follows is an excerpt from the foreword.

BLUE BOY BLUES

As a painting you must have heard a lot about me,

For I lived here for many happy years;

Never dreaming that you could ever do without me

Till you sold me in spite of all my tears.

It's a long way from gilded galleries in Park Lane

To the Wild West across the winter sea.

If you don't know quite what I mean,

Simply ask Sir Joseph Duveen

And he'll tell you what he gave 'em for me.

For I'm the Blue Boy;

The beautiful Blue Boy;

And I am forced to admit

I'm feeling a bit depressed.

A silver dollar took me and my collar

To show the slow cowboys

Just how boys

In England used to be dressed.

Cole Porter, the great 20th-century American songwriter, wrote this amusing ditty in 1922, ostensibly for the London revue Mayfair and Montmartre. It lampoons railroad tycoon Henry E. Huntington's celebrated purchase a few months earlier of what was then arguably the most famous painting in the world: Thomas Gainsborough's Blue Boy, painted in 1770. Huntington had acquired it through the business-savvy machinations of the most flamboyant art dealer of the day, Joseph Duveen, from its owner the Duke of Westminster for what was said to be the largest price ever paid for a work of art. Duveen, the Duke of Westminster, and the swoon-inducing price Huntington paid are all directly or indirectly mentioned in Porter's witty and highly topical song, while its references to cowboys and the Wild West flattered an urbane audience quick to equate California with the caricatures found in cheap novels and the nascent film industry.

Before shipping Blue Boy to California, Duveen—ever the showman—arranged for it to be exhibited at London's National Gallery for a month. An astonishing 90,000 people came to pay their respects, and the Gallery's director famously wrote "au revoir" on the back of the painting in the hope, no doubt, that it would someday return. It has never, however, left the estate to which Huntington brought it. The public reaction to the painting's departure for America (and California, of all places!) was a combination of sorrow, anger, dismay, and national pride. To understand this response, we should remember the extraordinary popular fame the picture had achieved in the century and a half since it had been made. We should also credit Duveen's brilliant marketing skills. Equally important, though, was what Blue Boy symbolized to the British people, and for that we must recall the great war they had just endured from 1914–18, the memory of which was still vivid.

Of the 8.5 million to 10 million soldiers killed in the war as a whole, more than 700,000 were from the United Kingdom and an additional 200,000 came from the British colonies. Additionally, 2 million British (and British colonial) soldiers were wounded, many grievously. "Indiscriminate slaughter" is a phrase often used to describe the brutality of this, the first fully mechanized war on a massive scale. In a single day of the Battle of the Somme, the British army alone suffered more than 57,000 casualties. By 1921, three years after the war's conclusion, the wounded were still everywhere in sight, on the streets of every city and village in Britain. The ceremonial funeral for the "Unknown British Warrior"—the most poignant and cathartic of all post-war commemoratives, attended by hundreds of thousands—had been held in November of 1920, less than a year before Blue Boy's sale.

Blue Boy & Co. highlights the richness and diversity of The Huntington's European collection. Images of more than 100 of the most impressive works housed at The Huntington—including paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, and works on paper—are published together for the first time in this handsome catalog (available fall 2015).

It is difficult not to conclude that at least part of the anguish of Blue Boy's leave-taking was its commingling in the public's mind with the leave-taking of their sons and brothers for the war, many of them never to return. An entire generation of young, healthy, handsome boys killed or mutilated, and now this: another son, another brother, symbolizing unutterable loss. And though the association of Blue Boy with Britain's heroic fighting men may strike us as improbable, given Blue Boy's undeniably androgynous appearance to modern eyes, it is useful to note that in the 19th century the painting was described as "the most firm, spirited, and manly portrait of youth ever painted." "Youth" is the operative word here, for youth is what the Great War utterly smashed, and this beautiful boy—pretty enough to appeal to both sexes—struck a nationalist and deeply emotional chord.

Blue Boy's fame remained undiminished for generations, its elegant form gracing every imaginable consumer product from tea towels to Christmas ornaments, devolving finally to kitsch, the surest sign of celebrity. But that fame, while not yet on life support, has been compromised in recent years, and what was once universally recognized now just as easily elicits a blank stare. This volume—the first ever devoted to a wide-ranging overview of The Huntington's collection of European art—hopes, in part, to reverse this trend. Blue Boy & Co. presents its eponymous subject in the rejuvenating context of its distinguished kin—paintings, sculpture, furniture, and decorative art of the highest quality—collected first by Henry and Arabella Huntington and substantially enlarged by subsequent curators and directors of the Huntington Art Collections from the 1930s to the present. And yet while Gainsborough's Blue Boy and Thomas Lawrence's Pinkie retain their minor celebrity status, and while The Huntington's collection of 18th-century British "Grand Manner" portraits is rightly known by many as the finest in the world, large parts of The Huntington's holdings of European art remain unfamiliar to the wider public.

At the same time, the "meaning" of Blue Boy—a painting once nearly as iconic as the Mona Lisa—has shifted and continues to shift over time. What, to contemporary audiences, do Blue Boy, or Joshua Reynolds' Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse, or John Constable's View on the Stour near Dedham, or Madame de Pompadour's tea service mean to today's audiences? What, for that matter, does it mean to have a major collection in Southern California of 18th- and 19th-century British art, accompanied by superb, if smaller, collections of Italian Renaissance, French 18th-century, and a smattering of Dutch and Flemish art? This book will not answer those questions. What it will do, we hope, is invite a second look at and a rethinking of these beautiful and compelling objects. It is gratifying that artists from Robert Rauschenberg (whose first acquaintance with Blue Boy, Pinkie, and Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse was transformational) to Kehinde Wiley (whose artistic practice is informed by his early experience of The Huntington's Grand Manner portraits) have found inspiration in The Huntington Art Collections. It is our hope that every visitor will have such epiphanies at The Huntington; this book is a tool in the service of that goal.

Kevin Salatino is Hannah and Russel Kully Director of the Art Collections at The Huntington.