Taxing Visions

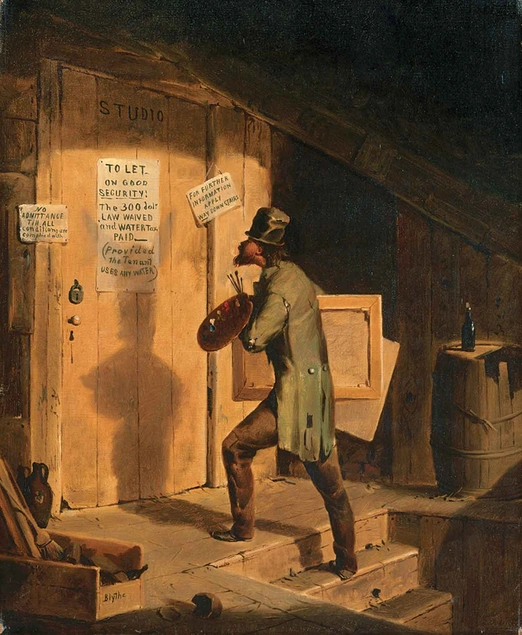

David Gilmour Blythe (1815–1865), Art versus Law, 1859–60, oil on canvas, 24 × 35 13⁄16 in. Brooklyn Museum. Dick Ramsay Fund.

James Henry Cafferty (1819–1869) and Charles G. Rosenberg (1818–1879), Wall Street, Half Past Two O'Clock, October 13, 1857, 1858, oil on canvas, 50 × 40 in. Museum of the City of New York. Gift of the Honorable Irwin Untermeyer.

Alfred Kappes (1850–1894), Tattered and Torn, 1886, oil on canvas, 40 × 32 in. Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Mass. Purchased with the Beatrice Oenslager Chace, Class of 1928, Fund; the Rita Rich Fraad, Class of 1937, Fund for American Art; the Kathleen Compton Sherrerd, Class of 1954, Fund for American Art; and with restricted acquisition funds

A new exhibition interprets the economic depression of the late 19th century

Taxes, rent, economic depression, and financial inequity: Sound familiar? If the words conjure up contemporary headlines rather than works of art, it’s not surprising. But in fact, these themes are the subject of a new exhibition. “Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art” opens Jan. 29 and continues through May 30 in the Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries.

Organized jointly by The Huntington and the Palmer Museum of Art at Pennsylvania State University, the exhibition challenges conventional wisdom about the period. Although the late 19th century is identified artistically with leisure-laden landscapes, abundant still lifes, and class-conscious portraiture, American artists also turned their attention to the financial and occupational turmoil that marked the Reconstruction, Gilded Age, and early Progressive eras. The 34 works in “Taxing Visions,” which are on loan from 31 museums and private collections, demonstrate with sometimes startling clarity the experience of economic downturn.

A diverse group of artists is represented in the exhibition, including William Michael Harnett, George Inness, Eastman Johnson, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Some worked in traditional academic styles and others in proto-modernist modes of Impressionism and Tonalism, depicting people from every income level and geographic region of the country—from the robber barons of Wall Street to homeless children hawking newspapers. The works relate closely to The Huntington’s permanent installation in the Scott Galleries.

“This exhibition sets the works in our American art collection in their social and economic context,” said John Murdoch, Hannah and Russel Kully Director of the Art Collections. “But it also celebrates the benefits of academic collaboration. The curators have created a thought-provoking experience for visitors with carefully selected examples illuminating a theme that’s at once timely and timeless.”

Kevin Murphy, the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington, and Leo Mazow, the former curator of American art at the Palmer Museum and now associate professor of art history at the University of Arkansas, co-curated “Taxing Visions” and co-wrote the accompanying catalog.

“Leo and I had a longstanding academic interest in this neglected field and are thrilled to finally bring it before the wider public,” said Murphy. “The topic became especially timely when the United States experienced its most dramatic economic downturn in decades while we were working on the exhibition.”

One of several heart-rending paintings in “Taxing Visions” is Tattered and Torn (1886) by Alfred Kappes. It depicts an African American woman dressed in rags, holding a lit match in her extended hand, so decrepit she can barely light her pipe. Unlike other artists of the period who sentimentalized African American subjects, Kappes painted with frankness and sensitivity the reality of his subjects’ poverty.

A reminder of the physical cost of the Civil War, Johnson’s The Pension Claim Agent (1867) shows a Union Army veteran in a humble New England home as he confronts a government agent who is there to verify the ex-soldier’s claim to compensation for his amputated left leg. Following the war, scenes such as this played out throughout the northern states. In 1865 only 2 percent of veterans received pensions; by 1870 the number had only slightly risen, to 5 percent.

Artists at the time suffered alongside their fellow citizens, and a group of poignantly humorous self-portraits reveals their own efforts to make a living while facing a hostile economic climate.

“Taxing Visions: Financial Episodes in Late Nineteenth-Century American Art” is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. The Huntington’s installation of “Taxing Visions” is supported by the Susan and Stephen Chandler Exhibition Endowment and funds from Steve Martin for exhibitions of American art.