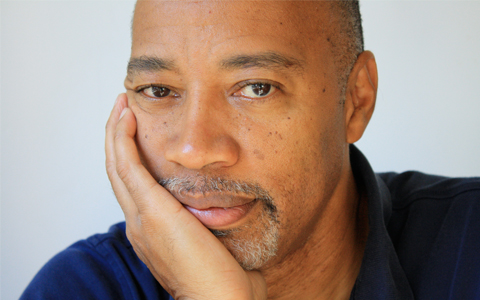

Kenneth Warren's latest book—What Was African American Literature?—is based on a set of lectures he delivered at Harvard a few years ago. This week he'll take the podium in The Huntington's Friends' Hall to share a bit from what he hopes will be part of his next book. His lecture takes place on March 2 at 7:30 p.m. and is free and open to the public. This morning at 9 a.m. PST you can also follow his Live Chat conversation with Henry Louis Gates Jr. on The Chronicle of Higher Education website. (Gates is the director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard University.)

Warren is Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor of English at the University of Chicago and the R. Stanton Avery Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington for 2010–11. His new book makes the case that what we call African American literature is the creative work written by black authors within and against the segregationist strictures of Jim Crow America.

"I'm not pushing for a particular end date for African American literature," explains Warren, "except to suggest that it is linked to the victories of the Civil Rights era, in which legal foundations that mandated segregation became dead letters by the mid-1970s."

In his previous book, So Black and Blue: Ralph Ellison and the Occasion of Criticism (2003), Warren took a closer look at the most famous author of that transitional era. Ellison famously came out of relative obscurity by publishing Invisible Man in 1952, winning the National Book Award in 1953, and then witnessing the passing of Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954 only to labor over his second novel for the rest of his life.

While Ellison was a prolific essayist, his struggle to write fiction might have stemmed, Warren says, "From the fact that he had so long been focused on engaging the problems of Jim Crow America, and in some way he sort of wrested his artistic power from having to think about and respond to the humiliations of a Jim Crow society."

In his Huntington lecture—and future book—Warren is more concerned with exploring the emergence of African American literature in the wake of yet another famous legal case, Plessy vs. Ferguson in 1896, which upheld the constitutionality of "separate but equal."

Despite its failings, Reconstruction had at least given freed blacks citizenship and access to political life. But with the Plessy decision the door slammed shut for most blacks in the south. In response, writers like Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chesnutt, and Sutton Griggs felt it was their responsibility to speak for the disenfranchised.

In describing his upcoming lecture, Warren says, "I really want to drive home the crucial importance of disenfranchisement as a condition for the emergence of the idea that literature had to—and could—provide a voice for a largely silenced population."

If you miss Warren's Live Chat you can read it later . Also on the website of The Chronicle of Higher Education is Warren's recent article "Does African-American Literature Exist?" You can also learn more about Warren and his book on the blog of Harvard University Press.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.