This selection of quilts, made between 1850 and 1900, includes a wide variety of styles and patterns. The spinning wheel in the foreground dates from the early 18th century. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. Photo by Kate Lain.

An astonishingly rich installation of early American art provides a pre-Thanksgiving visual feast for Huntington visitors, beginning Oct. 22. That’s opening day for the new Jonathan and Karin Fielding Wing in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art.

On view in the elegant new space designed by Frederick Fisher and Partners is an inaugural exhibition of more than 200 works from the Fieldings’ magnificent collection of 18th- and early 19th-century paintings, sculpture, furniture, ceramics, metal, needlework, and other decorative arts that explore early American history through objects made for daily use and through images of the people who used them.

“Becoming America: Highlights from the Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection” reveals the creativity and distinctive genius of America’s early artists and craftspeople. Rather than collecting work made for the affluent residents of coastal cities like Boston, Newport, New York, and Philadelphia, the Fieldings have with a few exceptions focused on items created by craftspeople in rural New England. These are objects of beauty and utility meant for the burgeoning middle class—the farmers, merchants, ministers, and magistrates in villages throughout the northeastern United States.

The wall along the entryway into the Fielding Wing displays useful implements made of metal, including ice tongs, bootjacks, and long-handled tools for the fireplace. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. Photo by Kate Lain.

Along the entryway into the Fielding Wing, visitors will encounter an impressive wall of useful items made of metal—such as toasters, trivets, long-handled tools for the fireplace, and decorative bootjacks—that were an essential part of daily life in early America. In the 17th century, the iron used to make these objects was mined from open-pit sites throughout the Northeast and then refined in regional foundries. Once the impurities were removed, the iron was either cast into useful shapes in elaborate molds or hammered by blacksmiths into a wide variety of functional forms.

Even the most basic tools were often given remarkably inventive shapes and rich decoration. Examples include an Adam and Eve fireback, used to reflect and retain heat in a fireplace, and a leaping stag weathervane, made of a light copper material so that it could pivot freely in the wind.

A massive wall of quilts dominates another space in the gallery. Typically used as bedcovers, hand-stitched quilts added vivid color to American households in the late 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. They also offered women the opportunity to demonstrate their creative capacities, as they employed their mathematical skills, artistic imagination, and inventiveness. The complex stitches seen in early American quilts create subtle linear patterns that often form a dynamic contrast to the quilt’s bold overall design.

Maker unknown, Album Quilt (detail), ca. 1850, cotton. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. Photo by Kate Lain.

The quilts on view, made between 1850 and 1900, include a wide variety of styles and patterns. Notable among them are the complex Lone Star Quilt of 1850, the vibrant Album Quilt made around 1850, and the boldly graphic Diamond Amish Quilt, made around 1896.

A separate display focuses on mid-19th century American interiors, inspired by two watercolors—Joseph H. Davis’s Family Portrait of Charles and Comfort Caverly and Their Son Isaac of 1836 and Jacob Maentel’s Portrait of Hatter John Mays of Schaefferstown of around 1830.

Among the highlights presented in this space are a chest attributed to the New Hampshire shop of cabinetmaker Samuel Dunlap; a tall case clock by Benjamin Willard Jr.; three scrimshaw busks carved and decorated by sailors and used as stays in women’s corsets; and a chip-carved spoon rack. The display also features several shop signs, a small hat merchant’s sample, a pair of decorative fire buckets, and a powder horn, all suggesting the world beyond the confines of a domestic interior.

This gallery is arranged to suggest the interior of an American home in the mid-19th century. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection. Photo by Kate Lain.

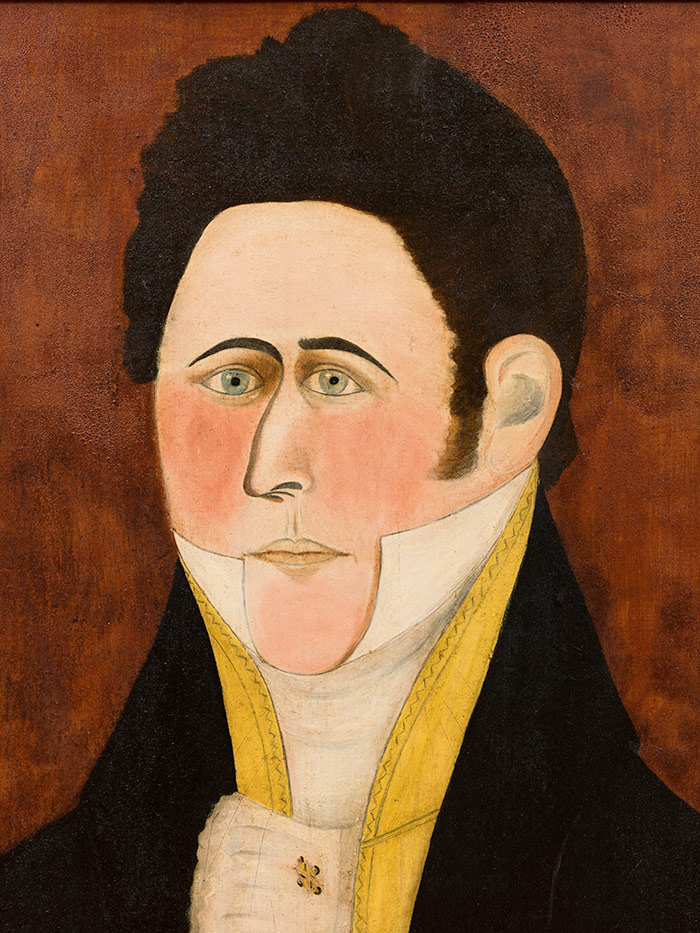

Portraiture has a room all its own. During the colonial era, portraits were generally bought only by wealthy merchants or royal officials in cities like Boston and New York. By the early 19th century, however, portraits decorated the parlors of middle-class homes throughout the Northeast.

One of the most impressive paintings on display is the Modigliani-esque Portrait of Albert G. Gilman (1831) by A. Ellis, about whom almost nothing is known. Only 15 portraits, all from the Readfield-Waterville area of central Maine, have been attributed to the artist. The sitter, probably Albert Gallatin Gilman (1806–1871), was a schoolteacher born in Mount Vernon, Maine. His steam-sculpted wool tailcoat with puffed sleeves and a notched collar employs the latest English tailoring and perfectly frames his cravat, jeweled stickpin, and crisply pleated shirt frill. A yellow waistcoat marks him as an unrepentant dandy.

Detail from Portrait of Albert G. Gilman of New Hampshire,1831, by A. Ellis. Oil on basswood panel. Jonathan and Karin Fielding Collection.

Visitors can extend their immersion in American culture through a new exhibition in the Chandler Wing of the Scott Galleries, “Real American Places: Edward Weston and Leaves of Grass,” and in the West Hall of the Library, where the second of two consecutive exhibitions focusing on the crucial role of national parks in American history opens: “Geographies of Wonder: Evolution of the National Park Idea, 1933–2016.” Both exhibitions start on Oct. 22.

So does “flORIlegium: Folded Transformations from the Natural World by Robert J. Lang,” an exhibition in the Brody Botanical Center of the Japanese art of origami, featuring more than 20 original works by the internationally renowned origami master Robert J. Lang. The display is open on weekends only. (Lang will give a free public lecture on the art and science of origami on Sunday, Oct. 23, at 2 p.m. in Rothenberg Hall.)

Kevin Durkin is editor of Verso and managing editor in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.