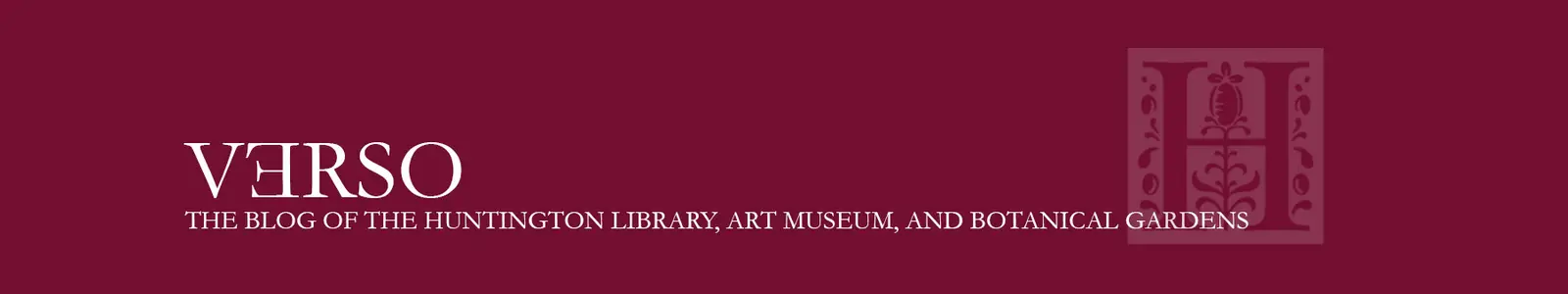

Scene in the House of Representatives on Jan. 31, 1865. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Feb. 8, 1865. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on Jan. 31, 1865, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, a resolution ending slavery.

The framers of the Constitution had forged a nation built on the rights of its citizens, but one that accommodated the peculiar institution of slavery. The tension between the ideals of liberty and the reality of human bondage was unsustainable. As Abraham Lincoln prepared to take office in 1861, seven states seceded from the Union. Just weeks after Lincoln became president, the nation succumbed to a long and bloody Civil War.

The following four documents are drawn from The Huntington’s renowned collection of rare Abraham Lincoln and Civil War manuscripts and appear in “The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery,” an exhibition on view in the Library’s West Hall. Each document presents a key element leading to the passage of the 13th Amendment to end slavery—Lincoln’s most significant and lasting accomplishment. And each features a signature by the nation’s 16th president.

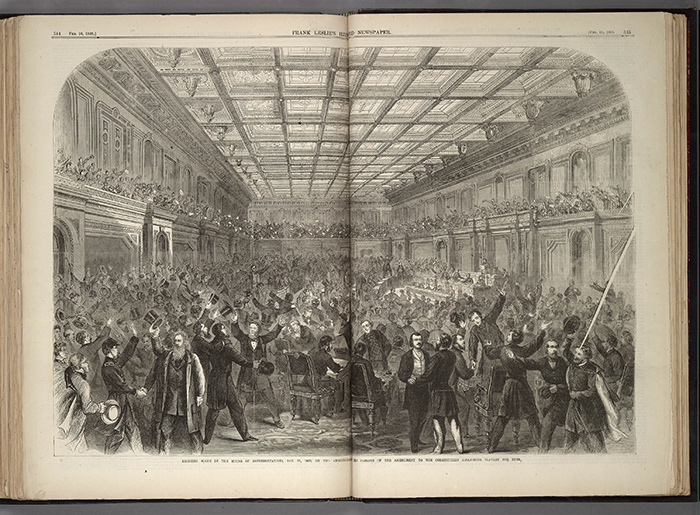

Lincoln’s position on slavery: Letter to Alexander H. Stephens

Even as president-elect in December of 1860, Lincoln revealed his formidable leadership skills, striking a conciliatory yet firm tone in a letter to the future vice-president of the Confederacy.

Lincoln offers assurances that his administration will not interfere with slavery in the Southern states, telling Stephens: “The South would be in no more danger in this respect, than it was in the days of Washington.”

Yet Lincoln makes clears his position: “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub.”

The back of Lincoln’s 1860 letter to the future vice-president of the Confederacy, Alexander H. Stephens. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

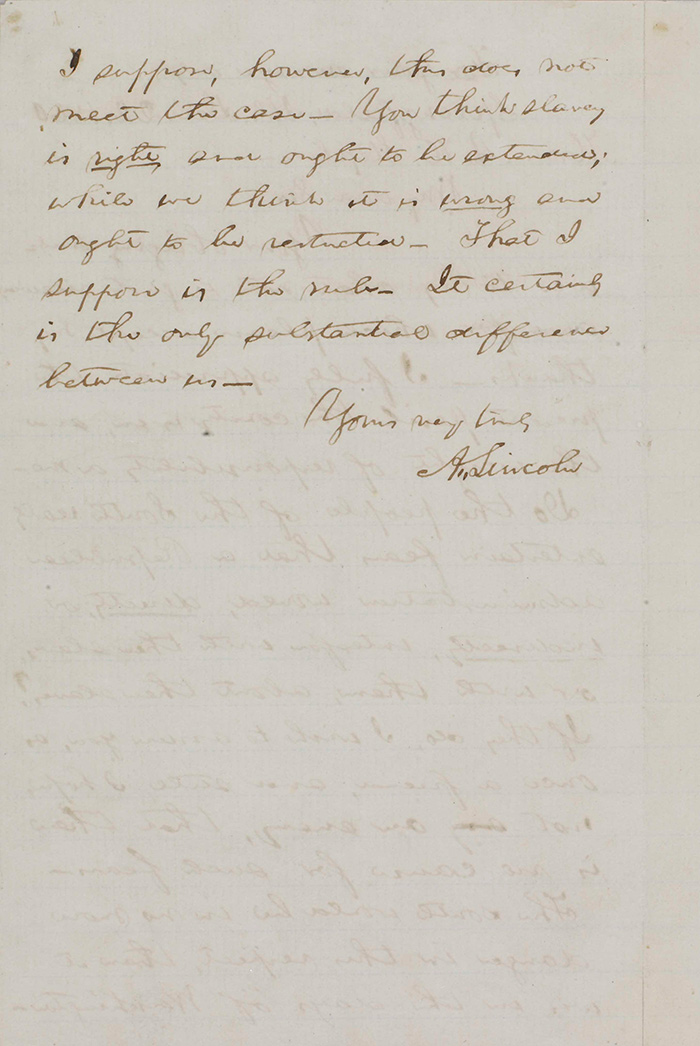

A partial victory: the Emancipation Proclamation

In his constitutional power as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863. It declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

The proclamation could not be enforced in areas still under rebellion, but it provided the legal framework to free more than three million slaves in Confederate areas that came under Union control.

The Emancipation Proclamation issued by Lincoln in his power as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Lincoln signed this print in June 1864; it was intended to be auctioned off at a charity event. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

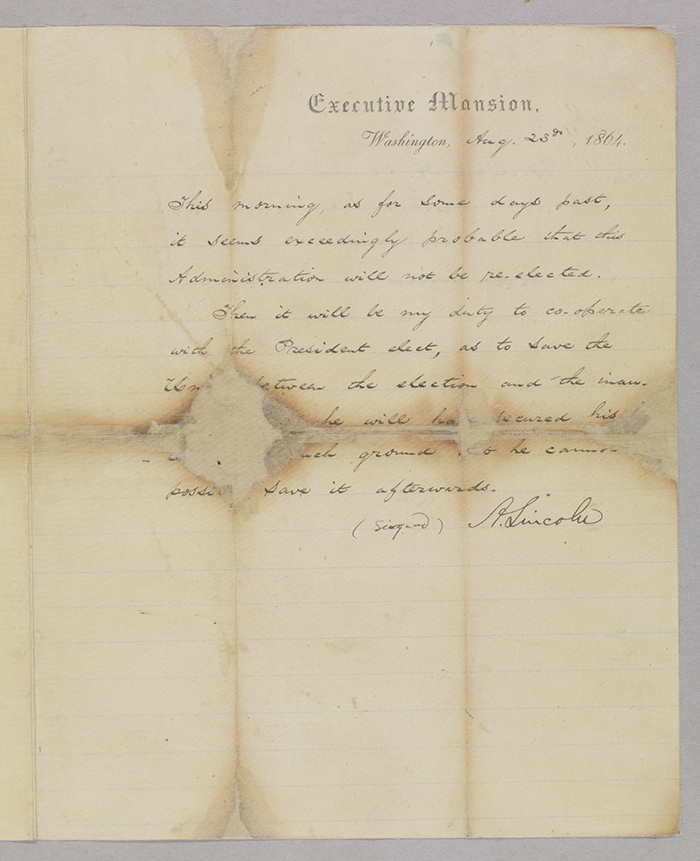

A second term? Lincoln’s Blind Memorandum

In the summer of 1864, with the Civil War raging into its fourth year, Lincoln knew that his chances for re-election depended on military success. Yet the Union effort had stalled, and he worried about the future of the nation under a new president. He wrote a letter indicating the urgency he felt to save the Union before the next president took office, then folded the paper and pasted it closed. At a cabinet meeting, he instructed his cabinet members to sign it without viewing the contents, a directive they followed. The letter, known as the “Blind Memorandum,” stated:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards.

— A. Lincoln

Though scholars debate what Lincoln meant by saving the Union, many interpret it as pushing for passage of the 13th Amendment.

Lincoln’s “Blind Memorandum,” a letter he asked his cabinet members to sign, sight unseen. The Huntington’s copy was made by one of the memorandum’s signatories, Gideon Welles, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

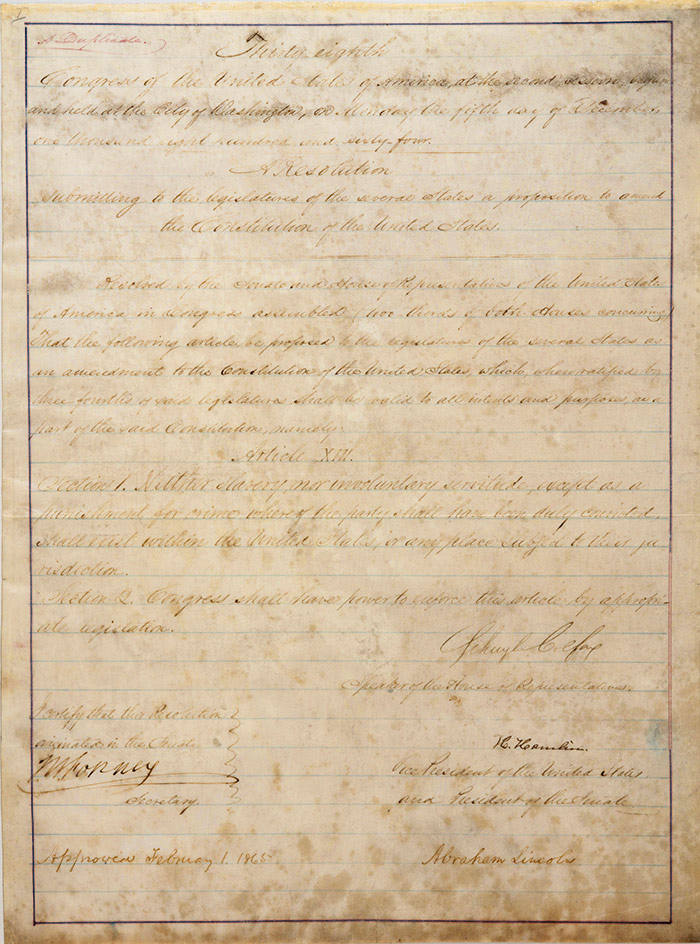

Victory: Passage of the 13th Amendment

Lincoln did win re-election. With that political hurdle behind him, he redoubled his efforts to secure passage of the 13th Amendment. The Senate had passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, but the House had failed to do so.

Lincoln and his cabinet stepped up their political maneuvering, reaching out to particular members of Congress to obtain the consensus needed to gain the two-thirds vote. On Jan. 31, 1865, the House of Representatives called another vote. A clerk read the tally: 119 ayes to 56 nays, with 8 abstaining. After a moment of stunned silence, the House erupted into celebration. The resolution had passed.

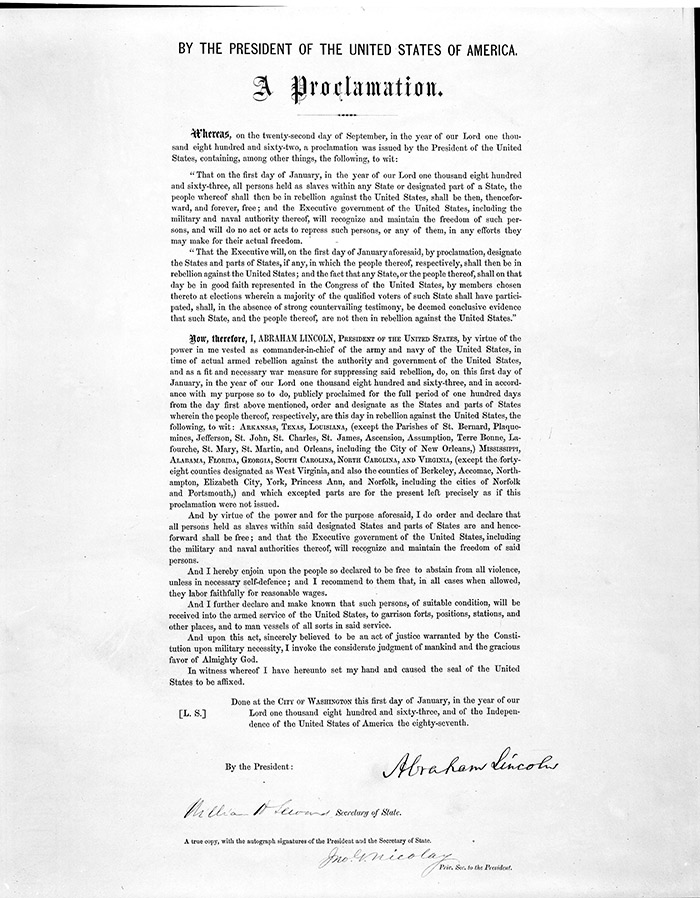

The president’s signature was not required for a constitutional amendment, though Lincoln signed several copies. The Huntington owns a souvenir copy made by chief engrossing clerk Isaac Strohm, who asked for Lincoln’s signature.

Lincoln would not live to see it become law. It took until Dec. 6, 1865, for three-quarters of the state legislatures to ratify it. Well before that, on April 15, 1865, just days after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth.

The amendment Lincoln worked so hard to attain would become law under the new president, Lincoln’s vice-president, Andrew Johnson.

Copies of the 13th Amendment signed by Lincoln, like this one known as the Strohm souvenir copy, were popular with collectors. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery” runs through April 20, 2015 in the Library’s West Hall.

In recognition of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, The Huntington has held a number of commemorative events.

In 2012, The Huntington held a Library exhibition, “A Just Cause: Voices of the American Civil War” and a concurrent photography exhibition, “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War.” You can still visit the web component of “A Strange and Fearful Interest,” which includes commentary by historians such as Gary Gallagher, Joan Waugh, and David Blight.

Talks from “Civil War Lives,” a 2011 conference that brought together some of the nation’s most renowned Civil War scholars for a two-day event, can be found on iTunes U.

In addition, many lectures exploring themes relating to the Civil War are available in a special page on iTunes U, “Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War.”

Related content on Verso:

“Remembering Gettysburg” (Feb. 19, 2014)

“Where Solomon Northup Was a Slave” (March 3, 2014)

“VIDEO | Voices on the Civil War” (Oct. 12, 2012)

“Capture the Flag” (April 12, 2011)

“Mystic Chords of Memory” (March 4, 2011)

“Many Happy Returns” (Feb. 16, 2011)

Diana W. Thompson is senior writer for the office of communications at The Huntington.