Map XI from William Smith’s atlas, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, 1815. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

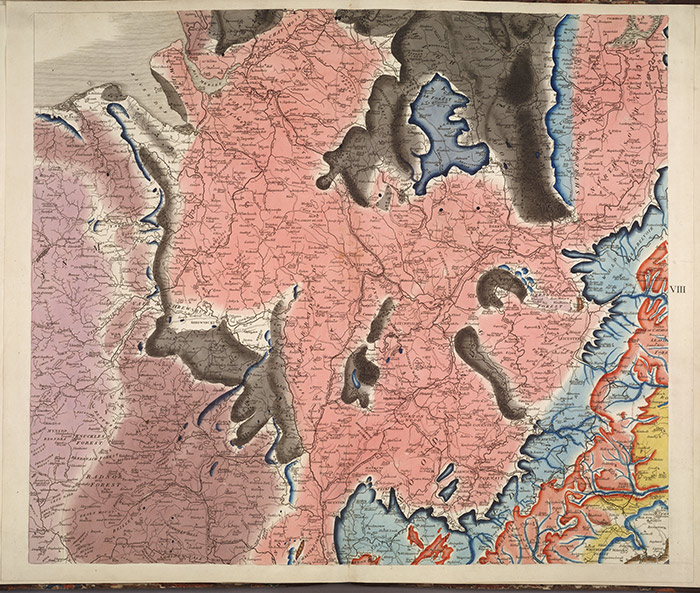

In 1815, a surveyor named William Smith published a huge, 10-by-16-foot map of England, Wales, and part of Scotland titled A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales. Up until then, explorers had sketched fairly accurate maps of land’s extent and contours. Smith’s hand-colored map indicated the geologic units exposed at the Earth’s surface, and, by extrapolation of the layer orientations, the rocks that lay below the surface.

Smith’s map, and others based on the same geological principles, have helped us reconstruct the history of the Earth’s continents, predict the location and extent of the world’s natural resources, gain insights into the causes of natural disasters, and learn crucial clues about the origin and evolution of life. His map changed our understanding of the world.

The story of Smith and his map has been brought to life by best-selling author Simon Winchester in his engaging book The Map that Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. On Dec. 8, Winchester will give a lecture titled “William Smith: The Man, His Map, and the Democratization of Geology” in Rothenberg Hall at 7:30 p.m.

Map XII from William Smith’s atlas, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, 1815. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As the orphaned son of a blacksmith in Churchill, Oxfordshire, young William Smith (1769-1839) was known for his intense curiosity. He was fascinated by the different types of fossils that eroded out of the local rocks and were used as measurement units (“poundstones”) and as toy marbles. As a teenager, he became apprentice to a surveyor and kept a diary of the geologic features he encountered.

At 23, Smith was hired as lead surveyor for a canal that would cross Bath. While digging the canal, Smith kept track of each unique rock layer, recognizing that despite the constant elevation of the canal, the rock layers were shallowly dipping down to the east, so that as one traveled west, one would predictably travel through older and older layers of rock.

This observation would later enable geologists to understand the history of the changing surface of the Earth. A few years later, Smith, an avid fossil collector, discovered that even when layers of rocks looked quite similar, they could always be distinguished by their specific fossils, a key observation for Charles Darwin’s future studies.

Map X from William Smith’s atlas, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, 1815. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Smith needed only one final puzzle piece to begin his life’s work, which he found in 1798 when he saw a color-coded map of soils made by local landowners John Billingsley and Thomas Davis. Smith immediately realized that, with this color-coding technique, he could create a map of the geologic layers on the surface.

Smith became determined to map the entire kingdom of Great Britain. He proceeded to spend the rest of his money and the next 15 years of his life moving from inn to inn across England and Scotland, walking great distances to single-handedly survey all of the outcrops of rock he could find and carefully tracking the rocks, their angles, and the fossils within them.

His geologic map is a work of art with carefully typeset letters and hand-colored geologic units. Published 200 years ago, it is still incredibly accurate and represents one of the single most significant contributions ever made to science.

Map VIII from William Smith’s atlas, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, 1815. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Sadly, the man who would later be called the “Father of English Geology” did not at first receive the acclaim he deserved. He lacked the foresight to copyright his map, and it was quickly plagiarized by the British Geological Survey. Their 1819 map drove the price of Smith’s map down and propelled him into bankruptcy. After years in debtor’s prison, Smith lost his home and was consigned to poverty as an itinerant surveyor for more than a decade.

Smith finally gained recognition in 1831, at the age of 62, when he received the first-ever scientific medal in geology, the Wollaston Medal. He lived the last nine years of his life in relative prosperity and peace.

Come to Simon Winchester’s lecture to learn more about a scientific genius whose work continues to inform the way we view our planet today.

The Claremont Colleges Library’s copy of William Smith’s map, A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, published in 1815, at the Honnold-Mudd Library in Claremont. This map will be on display in a classroom adjacent to Rothenberg Hall for half an hour before and one hour after Simon Winchester's talk about William Smith on Dec. 8. Annie Wilker (left), senior paper conservator at The Huntington, and Lauren Tawa, exhibits manager at The Huntington, take a close look at the map. Photo by Holly Moore.

A copy of William Smith’s map from Claremont Colleges Library will be on display in a classroom adjacent to Rothenberg Hall from 7:00 to 7:30 p.m. before Winchester’s lecture on Dec. 8 and from 8:30 to 9:30 p.m. afterward. A book signing also follows the lecture. The event is free and open to the public; no reservations required.

Kirsten Siebach is pursuing her doctoral degree in geology at Caltech. She has been a member of the science teams on several recent Mars missions for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, including the Phoenix Lander, Mars Exploration Rovers (Spirit and Opportunity), and the Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity).