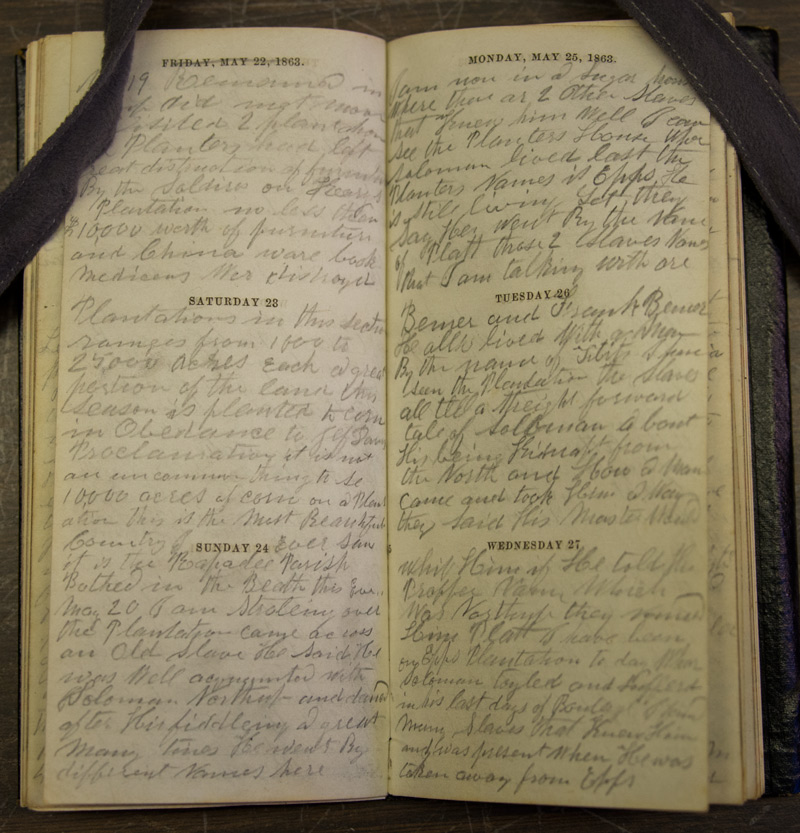

At the lower left of this opening to John Burrud's diary is a passage that reads, "Came across an Old Slave. He said he was well acquainted with Solomon Northup."

A war is seldom thought of as a sightseeing opportunity. Yet for many young men, the Civil War offered a chance to see places they had only read about in books. One such book was Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853), the harrowing tale of a free black New Yorker who was kidnapped, enslaved, and tortured on a plantation in Bayou Boeuf, La. The book is the inspiration of Steve McQueen’s Oscar-winning movie. Academy Awards also went to Lupita Nyong’o for best supporting actress and to John Ridley for best adapted screenplay.

In 1863, as the Union forces marched through Louisiana, Bayou Boeuf became a tourist attraction of sorts. The Union soldiers, especially from New York regiments, sought out the plantation of Edwin Epps, Northup’s cruel master.

One of these New Yorkers was John Burrud (1828–1883), an officer in the 160th Regiment of the New York Infantry. The collection of letters and diaries that Burrud kept between September 1862 and August 1866 now forms part of The Huntington’s manuscript collections.

When closed, Burrud's diary was small enough to fit into a breast pocket.

Burrud’s diary was the subject of a recent blog post by historian Adam Rothman. Says Rothman: “I had no idea when I opened it that Burrud’s diary would shed any light on Northup’s story and its legacies. In fact, I had been looking for something entirely different. History is full of surprises.” (See his post “The Horrors “12 Years a Slave” Couldn’t Tell” on the website of Al Jazeera America.)

Born in England and raised in New York, Burrud was a man of strong opinions and a clear sense of mission. He went to war to defend his “adopted country” against the Confederacy, a treasonous “empire” that had dissolved the sacred bonds of the Union to protect slavery—the “most damnable man degrading, soul killing, God dishonoring Institution that ever was permitted to exist on the face of the earth.”

Capt. Burrud’s war was nothing short of a “struggle for Human freedom.” He welcomed the Emancipation Proclamation and relished every opportunity to enforce it: “I think I can see its Death struggle and heare its Death Groans and Oh How I rejoice to see it writhe in agony!” Burrud also saw Louisiana blacks as the true American patriots, a freedom-loving people who “will lie down and have their heads cut off before they will go into slavery again.”

Yet the slavery that he encountered in Louisiana was very much alive. The horrified New Yorker saw men “come out of the woods with a heavey ring around their necks….this was as the Rebs expressed it to keep them from running away with the damd Yankeys.” Other fugitives never reached the Union lines; Burrud saw “a slave at Tibadeux jump in the Bayou and drowned Himself to get away from his Hellish Master.” Even those who had found refuge within the Union lines were in danger: “If they go outside of our lines, they will be picked up and taken off to slavery again.”

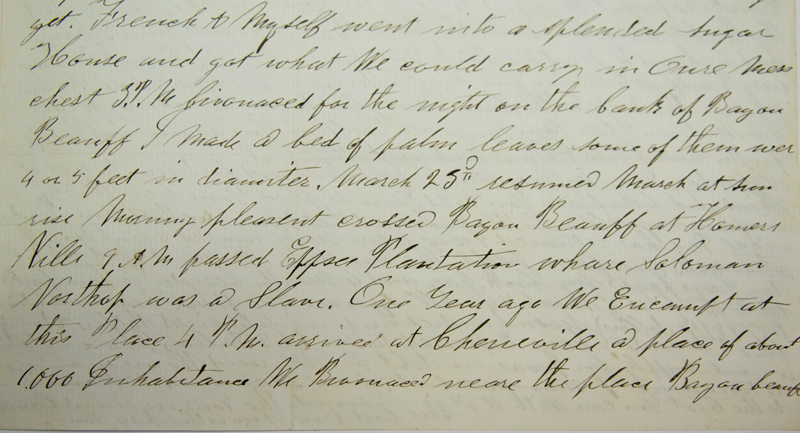

In a letter to his wife in March 1863, Burrud wrote that he had passed the Epps planation, "where Solomon Northup was a slave."

On May 17, 1863, Burrud and his men marched through the plantation belonging to “the Reble Governor” Thomas O. Moore. As the men marched on, “Oure band struck up and the Collord girls fell in line with the Regt. and danced along the road until sun down.” This, Burrud thought, was probably “the place that Solomon Northup operated.” He found Epps’ plantation two days later and interviewed several slaves who remembered Northup. A slave “named Washington” also showed the New Yorker “their instruments of torture—the Stocks, Whip, and Paddle, and Strap.” The slaves, he stressed, “all tell a straightforward tale…. Solomon’s book is true to the letter, only it does not portray the system as bad as it is. It is not in the Power of Man to do it.”

Burrud’s outrage was rare but by no means unusual. Other Union soldiers made a point to seek out tangible evidence of slavery’s inhumanity. This sort of “war tourism” served to remind the North that slavery was a real and powerful evil that just might survive the war.

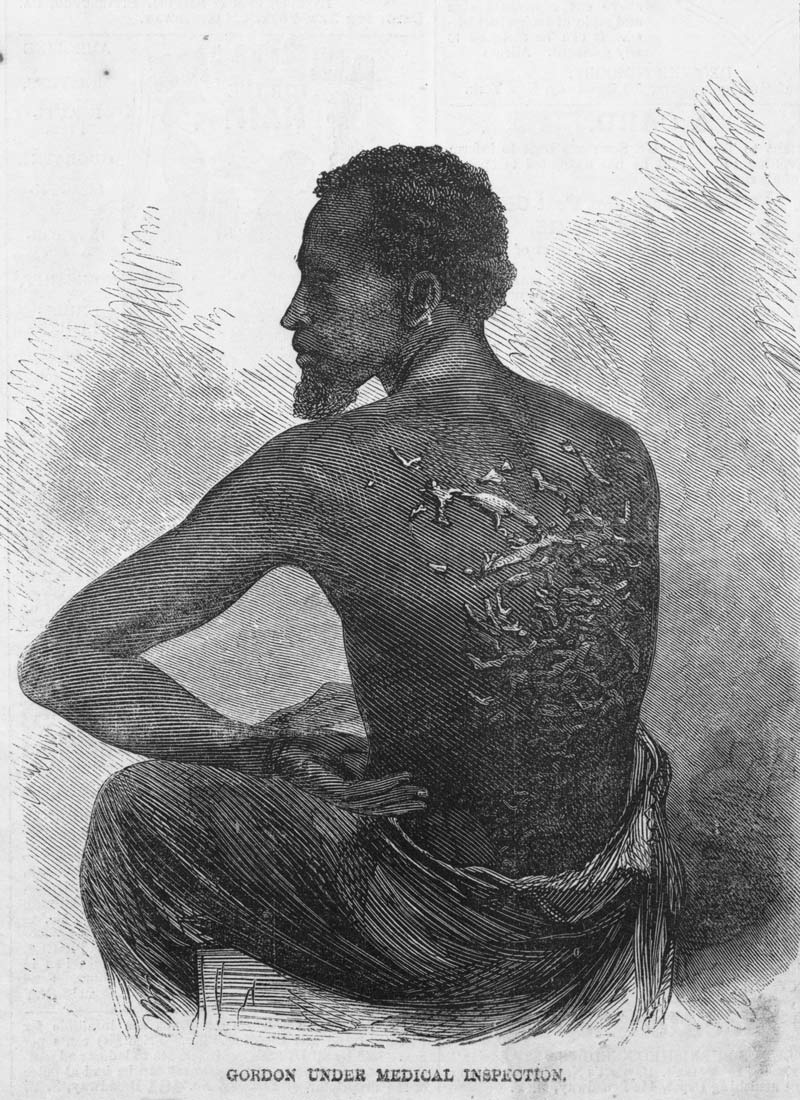

Another reminder of slavery’s inhumanity was this famous image. In 1863, a Union surgeon, horrified by the look of a Louisiana man whose back was covered with scars left by his owner’s whip, took a photograph of the man identified as Gordon. On July 4, 1863, the image appeared in Harper’s Weeklywith an article titled “A Typical Negro.”

Duncan McKercher (1819–1900), an officer of the 10th Wisconsin Regiment of Infantry, captured at the battle of Chickamauga, was imprisoned at Charleston’s Workhouse, the city’s notorious jail for slaves. While waiting to be transferred to Libby Prison, he found notes from South Carolina slave owners to the workhouse’s master requesting various forms of punishment for their runaway “property.” These included gruesome torture such as pouring vinegar on the wounds left by “paddles” and “straps.” McKercher held on to the notes throughout his imprisonment at Libby prison and eventually brought them with him after he was exchanged in March 1865. These notes are also part of The Huntington’s collections.

In addition to Adam Rothman's blog post, see Mary Niall Mitchell’s essay on the life and times of "12 Years a Slave" in the online journal Common-Place.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.