Valencia oranges are popular for juicing and eating out of hand. The Huntington’s orchard contains about 500 trees of this variety. Photo by Sandy Masuo.

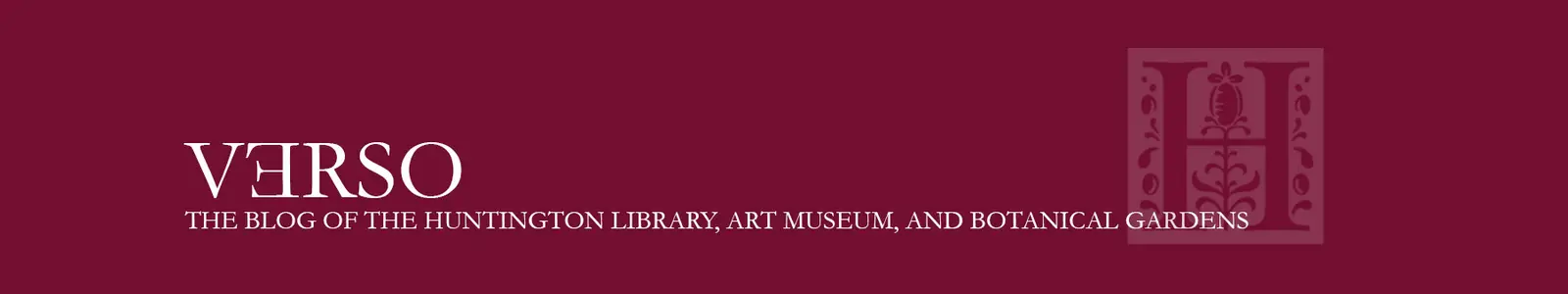

Anyone who has ever been overwhelmed by a bounty of fruit from a generous backyard tree faces an age-old challenge: how to store abundant, delicious, and nutritious fruit for leaner times. Among the time-honored options are drying and preserving with honey or sugar. The Huntington Library’s cookbook collection features entire volumes dedicated to the preservation of fruit. Among its rare books is a 1621 collection by John Murrell with the following exhaustive title: A delightfull daily exercise for ladies and gentlewomen: Whereby is set foorth the secrete misteries of the purest preseruings in glasses and other confrictionaries, as making of breads, pastes, preserues, suckets, marmalates, tartstuffes, rough candies, with many other things neuer before in print.

Many spelling variations of “marmelada” cropped up in early English cookbooks. This volume, printed in 1621, includes marmalade recipe variations for other tart fruits, such as pippin apples and gooseberries. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

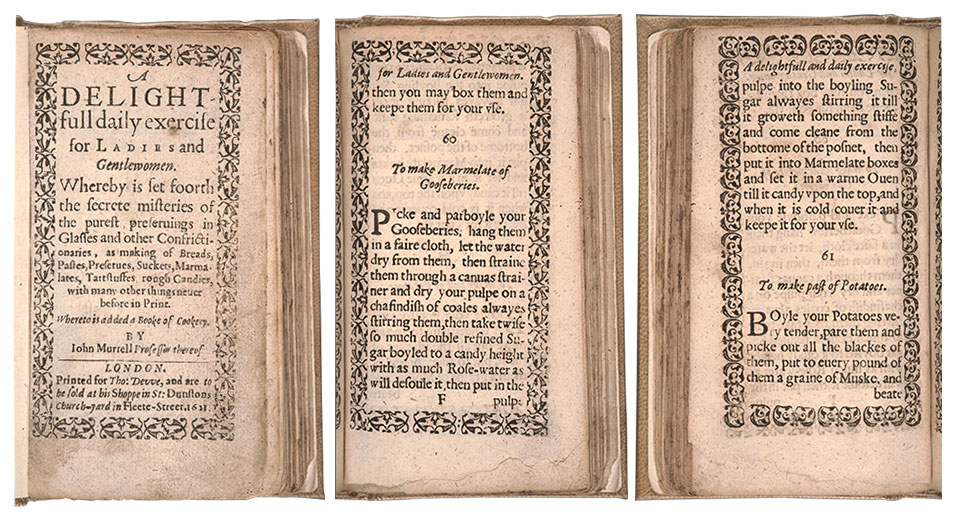

Fruit preserves include jams made from whole or cut-up fruit; jellies made from strained fruit juices and sugar; and marmalade, generally made from citrus, most often oranges. Bitter or sour orange varieties, such as Seville and bergamot, are almost exclusively destined for the cooking pot. They are the preferred fruit for marmalade in Britain, but the sweet oranges familiar to us as table fruit and juices, including Valencias and Washington navels, can also be made into marmalade.

The origin of the word “marmalade” is most likely “marmelo,” the Portuguese word for quince (Cydonia oblonga). Though not common in the contemporary American diet, the tart, tough quince is an apple relative native to parts of the Mediterranean. At some point, humans learned that it was possible to transform the abundant quince—which is almost inedible raw—into a delicious confection by cooking it with honey or sugar. The resulting dense, sweet-tart paste was most often sliced and served as an after-dinner treat. It remains a popular cheese board item. Marmelada became a common Portuguese export, traded both far and near: It traveled with explorer Vasco da Gama all the way to India, and it frequently made appearances at the Tudor court in England, where it was a familiar treat. Sour oranges had been imported to England since around 1500, and culinary fate eventually led to the substitution of quince for this other unpalatably sour fruit. Thus, a beloved breakfast item was born.

The citrus industry promoted consumption of oranges with cookbooks such as this Sunkist-branded volume, published in 1940. It contains a recipe for orange marmalade. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Humans have been enjoying citrus for millennia, but the exact origins of these plants are something of a mystery, though they probably came from Southeast Asia. The dazzling variety of oranges, mandarins, lemons, grapefruit, and limes that we enjoy today has been cultivated over many centuries from about 10 wild species—some of which are now extinct—descended from a single ancestor that existed roughly 8 million years ago.

Oranges eventually made their way to Europe, initially introduced by the Romans, but later and more successfully through trade between the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa. A prominent feature of King Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles is an opulent orangery, where more than 1,000 of the frost-tender plants were kept inside massive galleries, insulated by walls more than 10 feet thick, during the winter months to protect them from freezing temperatures. The Sun King’s master gardener, André Le Nôtre, designed special portable planter boxes for them as well as a device for moving them indoors and out.

This untitled citrus box label, ca. 1905, is an example of a stock label, meaning it was not created for a specific customer. Areas were left blank intentionally for inserting a brand name and the grower’s address. A grower purchased a stock label and then hired a local letterpress printer to add the missing information. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The fruit was introduced to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 15th and 16th centuries. Today, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and the United States are among the world’s top citrus-producing countries. In the United States, citrus agriculture is concentrated in Florida and California.

In 1841, William Wolfskill planted the Golden State’s first commercial orchard, near what is now downtown Los Angeles. In 1903, Henry E. Huntington bought the ranch land on which The Huntington stands today and had it planted with orange groves as well as avocados. A few of the original trees survive today and still produce fruit.

Arbor Team Crew Leader José Antonio Lopez harvesting fruit in The Huntington orange orchard. Photo by Sebastian Tovar.

Around the same time, Edwin Waldo Ward Sr., founder of the company that currently crafts The Huntington’s sweet orange marmalade, was planting the seeds of his future business. In 1891, he had relocated from New York to Sierra Madre, California, where he purchased 10 acres of land and planted it with navel oranges. A salesman for a New York–based importer of luxury foods, he had an interest in fine cuisine as well as a multitude of connections in the business.

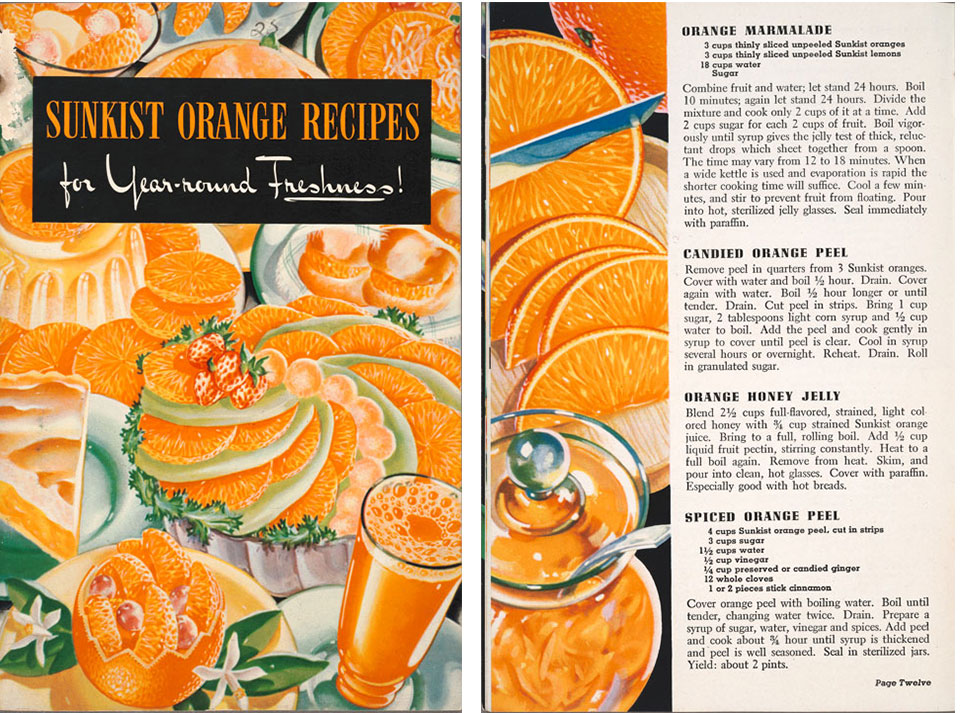

Richard Ward, grandson of Edwin Waldo Ward, in the kitchen preparing a batch of orange marmalade. Photo courtesy of E. Waldo Ward & Son.

In 1902, Ward built the home and red barn on Highland Avenue that are still used today by his company, E. Waldo Ward & Son. After retiring in 1915, he devoted his energies to creating the perfect English-style orange marmalade. He imported two Seville orange trees, the source of classic bitter orange marmalade. Ward’s business thrived. A couple of the progeny from those trees, now more than a century old, still survive on the 7 acres that remain, the last commercial grove in Los Angeles County.

Eventually, the legacy of his interest in orange marmalade led his great-grandson, Jeff Ward, to cross paths with The Huntington. In 2003, the Huntington Store and the Botanical Gardens teamed up with E. Waldo Ward & Son to produce the sweet orange marmalade sold in the gift shop—a bestseller since it was introduced nearly 20 years ago.

The Huntington’s sweet orange marmalade has been a bestseller since its debut in 2003. Photo by Sebastian Tovar.

Today, about 500 Valencia trees grow in The Huntington’s orange orchard. Some of the fruit is harvested by and donated to Food Forward, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit organization that brings fresh surplus produce to people experiencing food insecurity. Other oranges are transformed into sweet marmalade. So, the next time you open a jar of The Huntington’s finest, enjoy a dollop of citrus history with your breakfast.

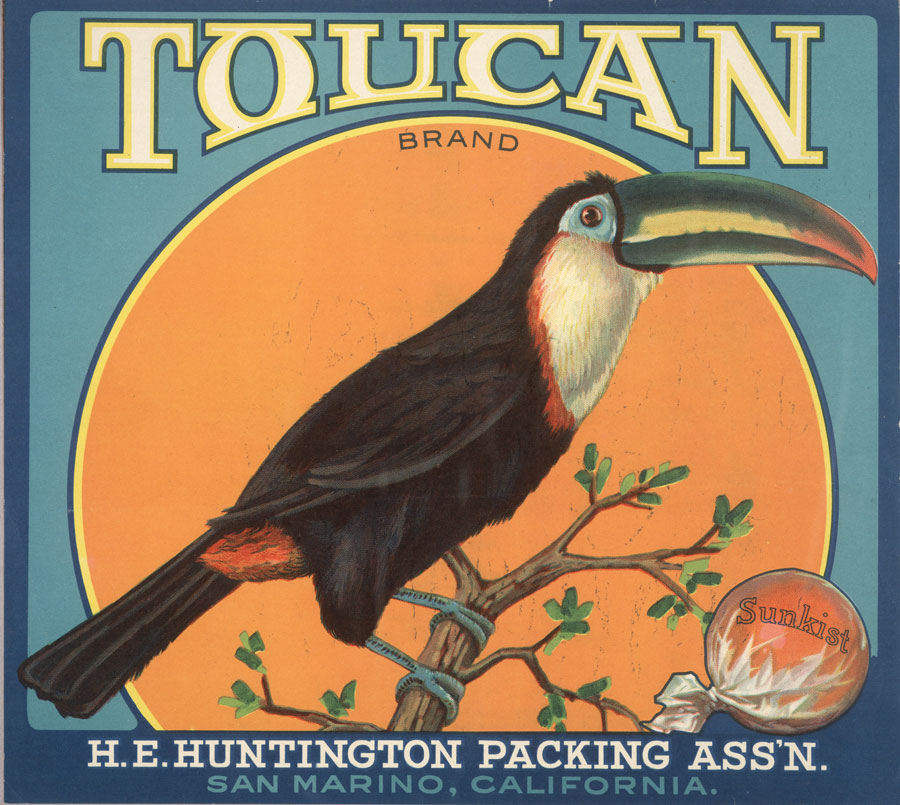

This colorful Toucan Brand citrus crate label was designed for the H.E. Huntington Packing Association, San Marino, California, in 1919. Gift of Jay T. Last. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

You can order Huntington Sweet Orange Marmalade online at the Huntington Store.

Sandy Masuo is the senior writer in the Office of Communications and Marketing at The Huntington.