William Deverell, the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, chats with USC doctoral student Andie Reid about her research. This is part of a series highlighting the work of USC graduate students.

WD: What's your dissertation about?

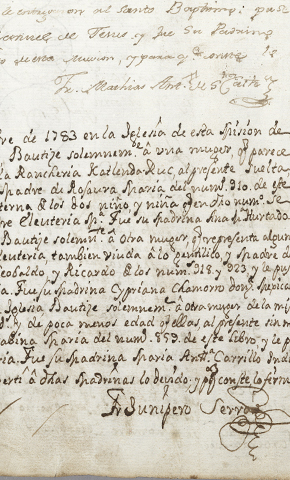

AR: It examines how Franciscan missionaries in colonial California ministered to the medical needs of Native peoples during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. My working title is "Medics of the Soul and Body": Disease, Health, and Medicine in Alta California, 1769–1850. The first part of the title comes from a 1745 publication written by a Sicilian priest, Francesco Cangiamila, whose treatise instructed other priests on how to perform caesareans on recently deceased pregnant women. California missionaries studied the treatise and performed postmortem caesareans on expectant Indian women who died during childbirth. One of the chapters of my dissertation deals specifically with this practice during the mission period. My sources include church records, government records, and correspondence as well as medical, anthropological, and ethnographic data.

WD: What do we already know about this topic?

AR: Demographic analyses from scholars such as Sherburne F. Cook, Robert Jackson, John Johnson, and Steve Hackel reveal that life in the missions was characterized by high mortality among Native populations. This enormous loss of life can be attributed to the introduction and spread of diseases introduced to California through European settlement. We also know that these diseases had a disproportionately adverse effect upon Native women. Fertility rates among indigenous women of child-bearing age plummeted during the colonial period, accelerating the overall population decline among California's Indians in the Spanish and Mexican periods.

WD: What don't we know that you are going to tell us?

AR: While the adverse consequences of missionization on Native health are generally acknowledged among scholars, European and Native medical treatments used to counter the effects of disease remain understudied. By focusing on remedies—usually the domain of anthropological studies—I hope to illustrate the process of medical knowledge exchange between Europeans and Natives. I'll also examine responses among missionaries to their own ailing health, an area that has been historically overlooked.

WD: Where do you do your research?

AR: I conduct the bulk of my research at the Huntington Library, whose collections are incomparable in the field of California studies. My research has also taken me to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, the Santa Barbara Mission Archives Library, and the Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library at the University of California, Los Angeles. I hope to travel to Mexico City this summer to use the collections at the Archivo General de la Nación.

Baptismal register from Mission San Carlos, signed by Father Junipero Serra, 1783. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical gardens.

WD: What's the best part of doing this kind of research?

AR: The best part is being able to dig into the archival record. I love the stuff of history—a reader's marginalia on the pages of an aged book, an 18th-century friar's complaint of an upset stomach, an indigenous man's petition to disaffiliate from the mission where he spent more than 50 years of his life. From these I get a glimpse into how past peoples made sense of their worlds.

Of course not every shred of evidence is meaningful and archival silences invariably punctuate the research process. I like to equate historical research to investigation, where the scholar is presented with a puzzle that she must decipher using fragmented data. These data illuminate, surprise, and frustrate. They force us to constantly rethink the kinds of questions we ask of our sources. It is challenging but never dull.

WD: Who are your role models in terms of figuring out about the West?

AR: The work of David J. Weber has been incredibly important to my intellectual development. He took disparate fields—American, Latin American, and Native American histories—and placed them in conversation with one another in an elegant and accessible style. I believe that his body of work is responsible for the renewed interest in borderland histories not only of the U.S. Southwest but also other regions of North and South America.

WD: What will your dissertation do for our broader understandings of the American West?

AR: I hope that my work will defy the conventions of American Western history. It is true that any study of California will, by default, be an American Western one because of this region's geographic coordinates. Yet my work—like that of David J. Weber—will demonstrate that California's past is inseparable from the histories of early America, Latin America, and Native America as well as the Atlantic and Pacific worlds. By bringing together these different historical perspectives, I hope my work crosses the traditional boundaries of scholarship and challenges the popular notion that California's history begins in 1850.

Andie Reid is a recipient of an ICW summer fellowship, which will help fund her research trip to the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City. She is also the recipient of summer awards from the Del Amo Foundation and the USC Science, Technology and Science Initiative. She was the lead data entry assistant for The Huntington's Early California Population Project, a comprehensive database of the sacramental registers—the baptismal, marriage, and death records—from California's 21 missions. She will complete her dissertation in spring 2012.

William Deverell is the director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West (ICW).