This post is co-published with the Getty Iris.

Paul Caponigro (b. 1932), Tralee Bay, County Kerry, Ireland, 1977, gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 × 13 1/4 in. © Paul Caponigro

It may come as no surprise to you, savvy reader, that the years spent preparing for a major exhibition are fraught with considerable challenges and no small amount of pain. An elusive loan, an uncooperative colleague, an intransigent donor, an unanticipated expense are only a few of the obstacles strewn along the curatorial path. In most cases, the outcome is worth all the trouble. There is deep satisfaction in bringing new or long-forgotten work to light.

As an example, photographer Minor White (1908–1976) was a giant in the field, but he is known today by only a relative few. The breathtaking retrospective now finishing its run at the Getty—which also includes work by White’s former students Paul Caponigro and Carl Chiarenza—introduces the artist to a generation that has never owned a film-loaded camera or printed a picture by hand. White’s deep dedication to his craft and luminous photographs inspire anew.

Exhibitions can also offer the singular pleasure of getting to know a living artist in a meaningful way. Such has been my recent good fortune with not just one legendary photographer, but two. Preparations for "Bruce Davidson/Paul Caponigro: Two American Photographers in Britain and Ireland," an exhibition co-organized by the Yale Center for British Art and The Huntington (where it opens November 8) began in 2009. Over the past five years, Yale curator Scott Wilcox and I have made at least one annual trip to visit Bruce and Paul at their respective homes.

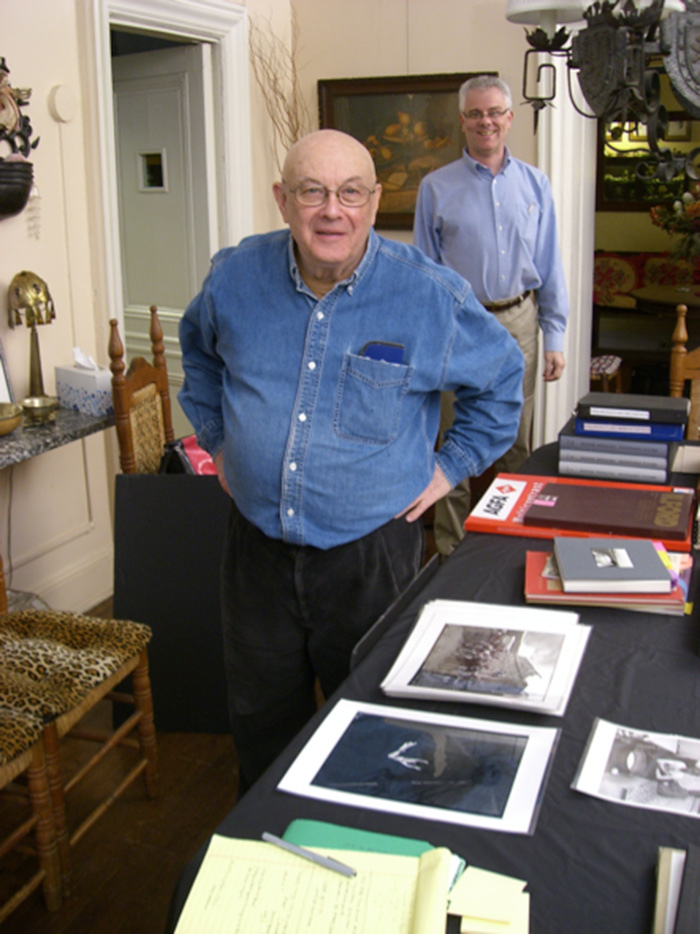

Yale curator Scott Wilcox (background) with Bruce Davidson at Davidson's home in New York City, 2010.

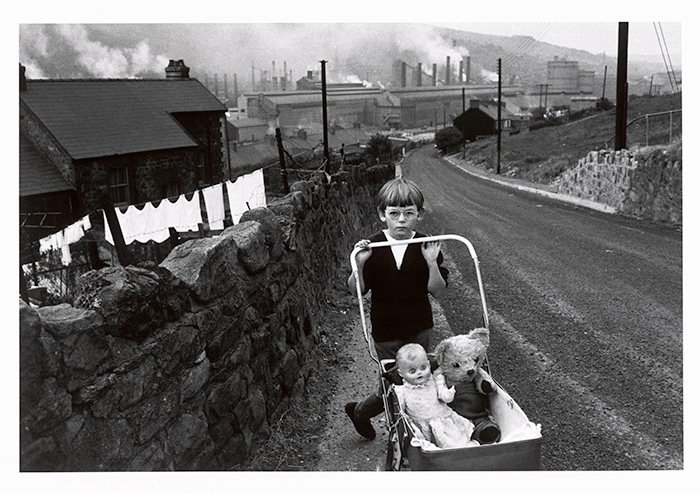

Now in their eighties, Bruce Davidson and Paul Caponigro are exact contemporaries whose paths had crossed but never converged. Each man blazed a distinct trail within the medium. Bruce was a photojournalist whose celebrated projects have ranged from teenage gang members to the Civil Rights movement, to Spanish Harlem and beyond. Paul’s illustrious career produced a ravishing body of black-and-white photography centered on the natural world.

While the temperamental and stylistic differences between the two are stark, the similarities proved, for me, all the more profound. As boys, they struggled in school and felt personally at sea. Each got a first camera at age ten. More sophisticated cameras came as a rites of passage when they turned thirteen: Paul for his Catholic confirmation and Bruce as a bar mitzvah gift. They remembered photography, even then, as holding out the promise of a happier life.

Bruce Davidson, Wales, 1965, gelatin silver print, 8 3/8 × 12 1/2 in.,Yale Center for British Art, Gift of Henry S. Hacker, Yale BA 1965, B2009.13.20. © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Both men got swept up in the Korean War’s compulsory draft. The Army sent Paul to San Francisco in 1953, where he met Ansel Adams and his West Coast crowd. The group included the aforementioned Minor White, who invited Paul to visit him in Rochester, New York, where he was relocating to teach. In the years that followed, White became Caponigro’s mentor, teacher, colleague, and friend.

The military was equally pivotal in setting Bruce’s artistic course, sending him in 1956 to Paris, where he met famed street photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. That important introduction ultimately opened the door for Bruce to join the elite Magnum agency, the photographers’ cooperative that Cartier-Bresson helped found.

Beginning in the 1960s, Davidson and Caponigro were deeply influenced by periods of creative exploration in the British Isles. It was this temporal and regional overlap that generated the idea for pairing the two in an exhibition.

Me with Paul Caponigro at his home in Maine, February 2014. Photo by Kate Lain.

Early on, Scott Wilcox and I discovered—somewhat incredulously—that despite award-winning, six-decades-long careers, Bruce and Paul had never met. But perhaps this was not as strange as it first seemed. For forty years, Bruce has lived in a comfortable, rambling apartment in New York City, where he has thrived amid the urban scene. Paul favored the wide-open spaces of the Southwest before finally settling more than a decade ago in a snug Maine cabin surrounded by trees. The two finally came face-to-face in mutual admiration at the Yale opening in June of this year.

There is something intimate and lovely about getting to know someone in the context of a home surrounded by a lifetime of things. The experience with these two accomplished artists over a period of years has far outweighed any of the predictable bumps in the road. It became the most satisfying part of the project by far. On the eve of the Huntington opening, I can honestly say (and I’ll speak for Scott here as well): Bruce and Paul, what a joy and a privilege it has been.

Scott Wilcox (center) with Paul Caponigro (left) and Bruce Davidson (right) as they meet for the first time at the opening of "Bruce Davidson/Paul Caponigro, Two American Photographers in Britain and Ireland" at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, June 2014.

Jennifer A. Watts is curator of photographs at The Huntington.