This large-scale vase, decorated with a perfectly balanced composition of stylized leaves and flowers, shows William De Morgan’s signature style, known as “Persian” in 19th-century England. Vase, designed by William De Morgan and decorated by Frederick Passenger, late 1890s, glazed earthenware, 13 3/8 × 11 in. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors’ Council, with additional support from the Adele S. Browning Memorial Art Fund. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

This gorgeous late 19th-century vase, designed by William De Morgan and painted by Frederick Passenger, has recently joined The Huntington’s collection. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors’ Council, with additional support from the Adele S. Browning Memorial Art Fund, it is now displayed in the Huntington Art Gallery. The vase features a harmonious arrangement of stylized flowers—carnations, tulips, and small bell-shaped blooms—painted in shades of purple, light pink, and blue, with olive green, cobalt, and turquoise leaves. Influenced by Middle Eastern colors and designs, and, specifically, by decorative motifs typical of ancient Syrian and Turkish pottery, De Morgan developed this distinctive style, referred to as “Persian” in 19th-century England.

A true polymath, De Morgan was an artist, designer, potter, and inventor, as well as a successful author in his later years. He began his career as a fine artist at the Royal Academy Schools in London but soon shifted his focus after meeting William Morris, a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement. De Morgan abandoned formal training to work on stained glass, tiles, and furniture design. Sharing Morris’ desire to counteract industrialization’s impact on craftsmanship, De Morgan championed the creation of beautiful, handmade objects produced using traditional methods. His commitment made him the leading ceramist artist of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Born in London in 1839, William De Morgan was raised in a liberal, intellectual household. His mother, Sophia Elizabeth De Morgan, was an advocate for social reform, supporting such causes as the abolition of slavery, prison reform, anti-vivisection, and women’s education and suffrage. She also co-founded Bedford College in London, the first women’s college in the United Kingdom. William’s father, Augustus De Morgan, was a renowned mathematician, the first professor of mathematics at University College London, and a suffragist. His writings sought to make academic ideas accessible to the public, a rare practice at the time.

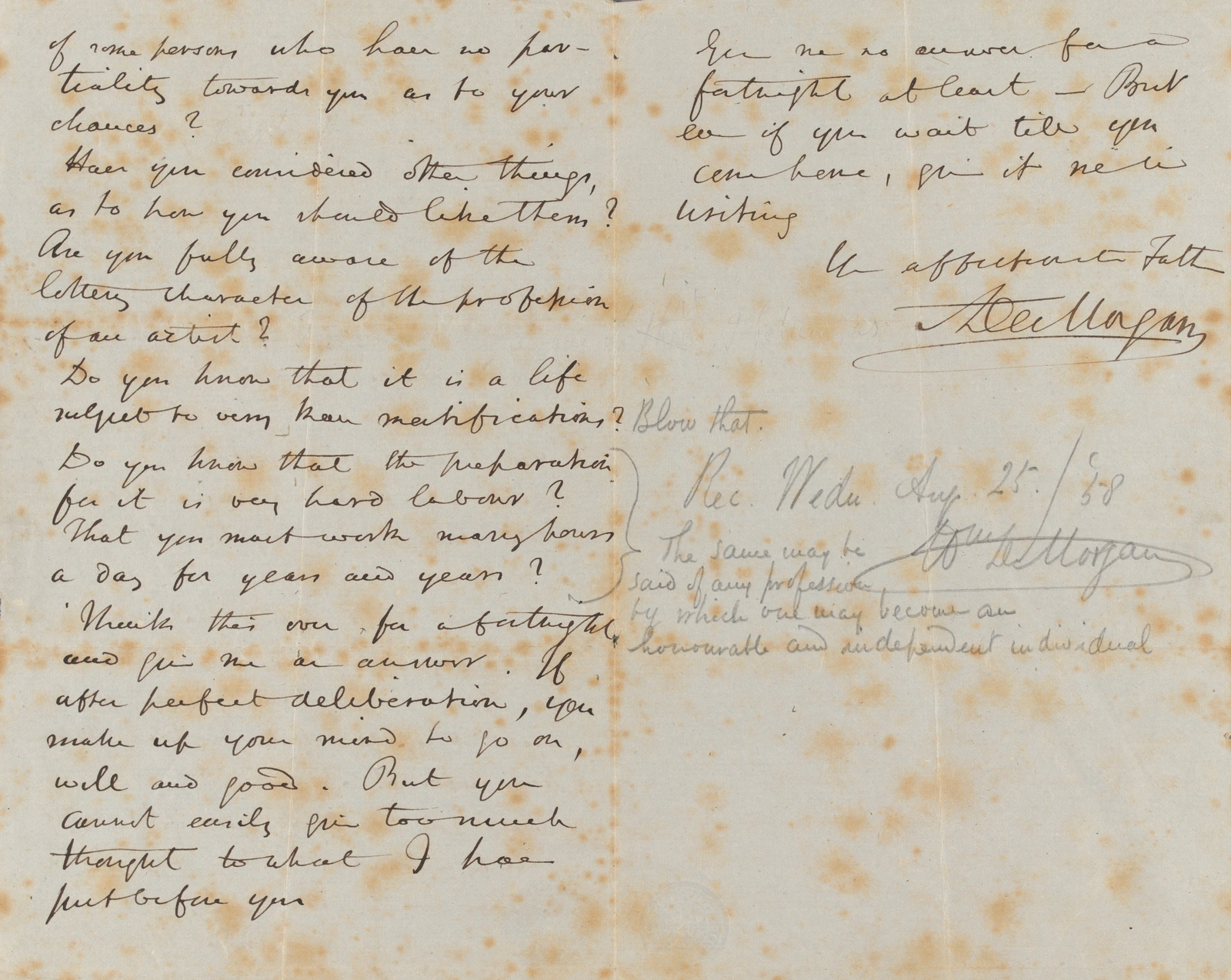

An Aug. 24, 1858, letter, held at The Huntington, captures an animated intellectual exchange between Augustus and his son William. In it, Augustus expresses concern over William’s decision to pursue art, while William’s penciled notes in the margin reveal his immediate reactions.

Dear Willy,

Now that you have fairly left college, it is time to ask yourself whether you have really made up your mind as to your profession—and if so, whether you have chosen wisely. I have never interfered because I cared little what you thought at seventeen or eighteen. Do you really think that you are likely to adhere to the choice you think you have made as to make it worthwhile to spend more time on it?” [“Yes,” reads a note by William.] “Are you fully aware of the lottery character of the profession of an artist? Do you know that it is a life subject to very keen mortifications?” [“Blow that,” William comments.] Do you know that the preparation for it is very hard labour? That you must work many hours a day for years and years?” [“That may be said for any profession by which one may become an honorable and independent individual,” William replies.]

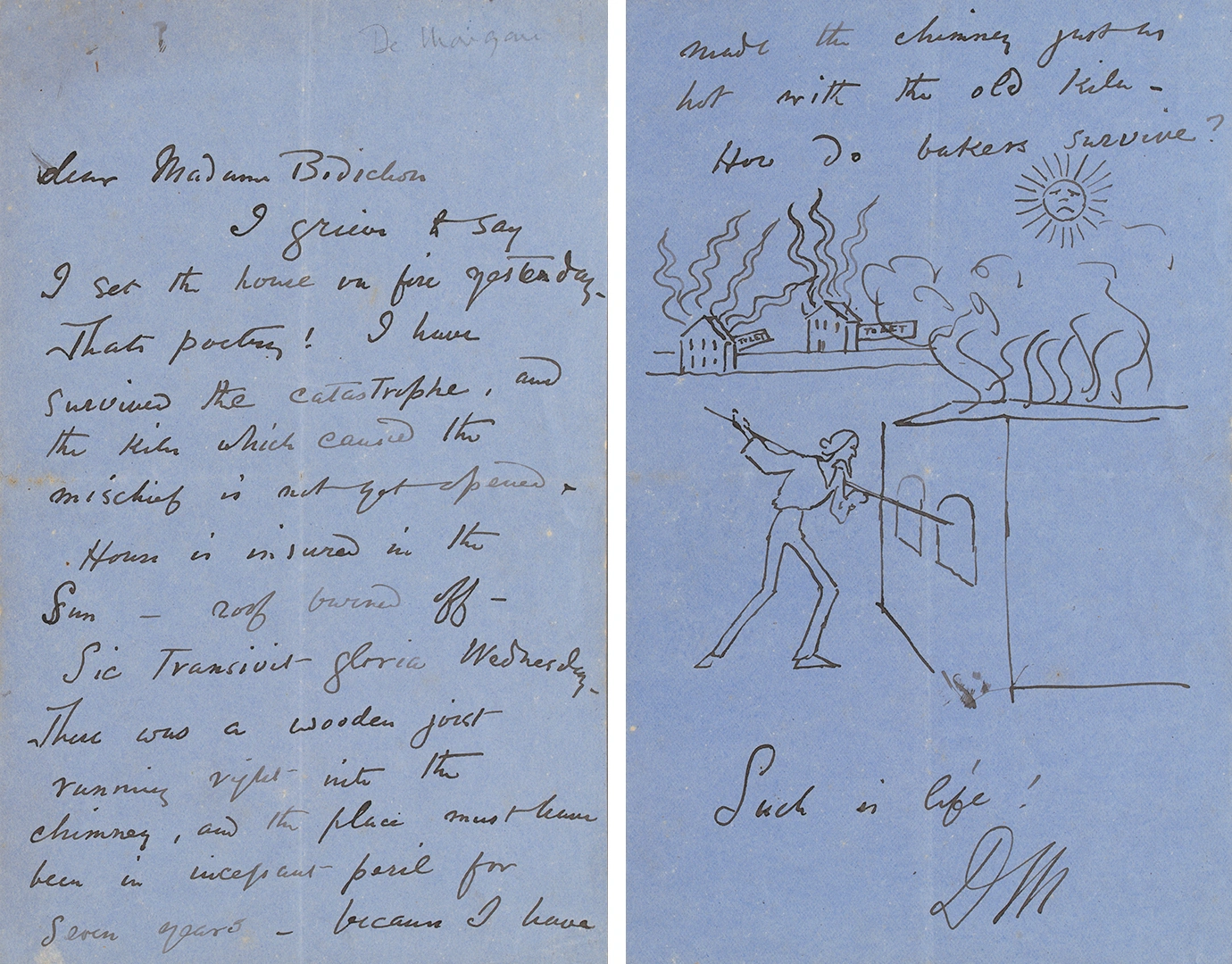

Letter from William De Morgan to Madame Bodichon, 1876. William Morris Papers, mssMOR 171–179, Box 5. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1869, De Morgan began experimenting with stained glass and tiles, setting up a kiln at his home in Fitzroy Square, London. The Huntington holds an individual tile and eight tile panels that he created.

In an 1876 letter to artist and activist Madame Bodichon, De Morgan humorously recounts setting his roof on fire while experimenting with a makeshift kiln. The letter, preserved at The Huntington, reveals his wit and includes a sketch of himself at the kiln. It concludes with a playful observation: “Made the chimney just as hot with the old kiln. How do bakers survive? Such is life!”

De Morgan’s scientific curiosity drove his exploration of decorative arts, particularly his work with glazes. His efforts to reinvent ancient Egyptian luster glazes earned him international recognition as the leading authority on luster in 1891 after he published an article titled “Lustre Ware” in the Journal of the Society of Arts. He also drew designs for specialized equipment and kilns, some of which are now housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

This is Evelyn De Morgan’s portrait study of the allegorical figure Salvation for a painting titled Angel Piping to the Souls in Hell, which is in a private collection. Evelyn De Morgan, Head of a Girl Playing a Reed Pipe, no date, pastel on brown paper, 14 1/2 x 9 1/4 in. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1883, De Morgan met Evelyn Pickering, a successful woman artist and advocate for gender equality and pacifism. The artists married in 1887, united by their shared values that aligned with the women’s suffrage movement and an opposition to war. In 1913, William actively supported the campaign for women’s voting rights—circulating petitions, contributing to the press, and serving as the vice president of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. Evelyn’s artwork frequently explored feminist and spiritual themes while critiquing materialism and violence. One such work is her pastel study of the allegorical figure Salvation, part of The Huntington’s collection. It was created for her painting Angel Piping to the Souls in Hell, now held in a private collection. This painting reflects the devastation of World War I and the theme of redemption through spirituality.

Vase, designed by William De Morgan and decorated by Frederick Passenger, late 1890s, glazed earthenware, 13 3/8 × 11 in. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors’ Council, with additional support from the Adele S. Browning Memorial Art Fund. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

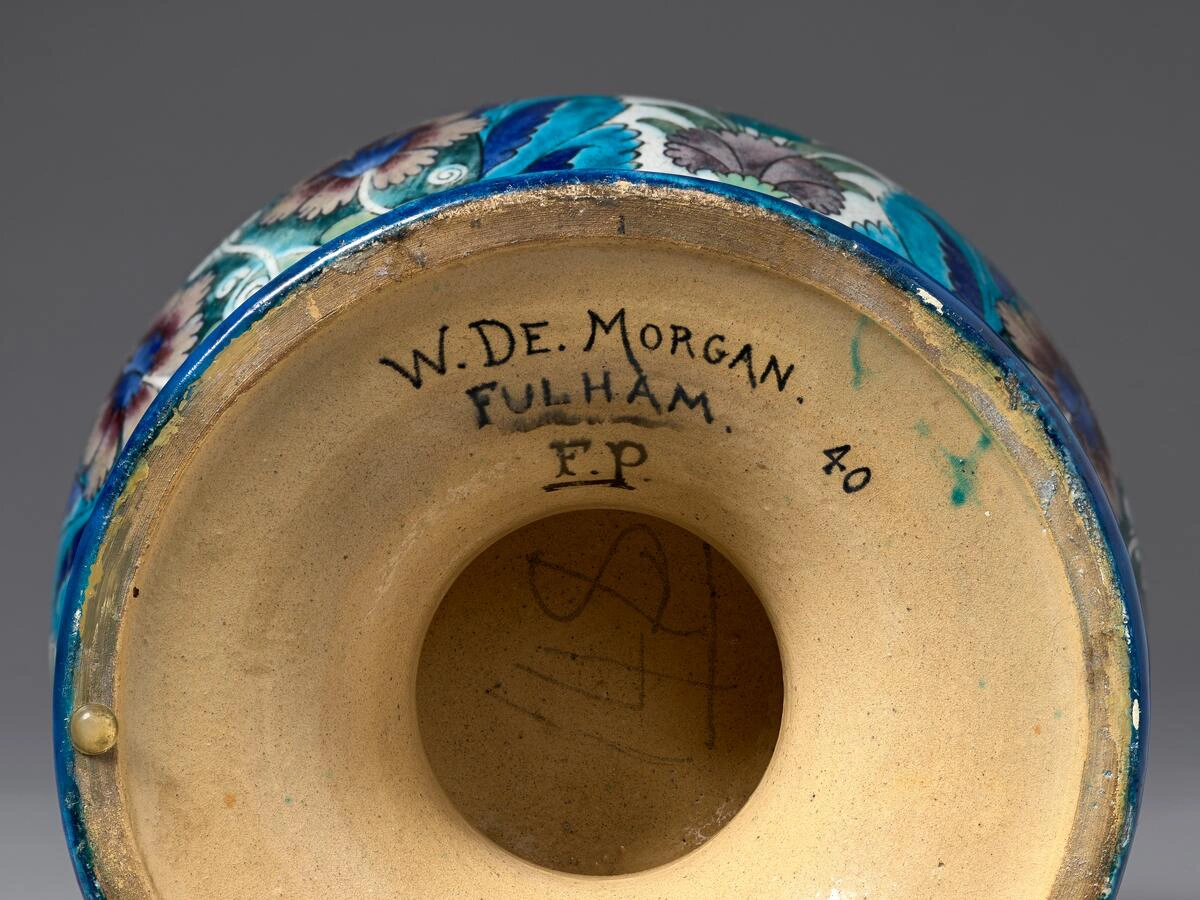

After the roof fire, William De Morgan committed fully to ceramic design. He opened an art pottery in Chelsea, employing a team to execute his designs. By 1887, he moved his operations to a purpose-built factory in Fulham, which is where the vase that’s now at The Huntington was crafted. The underside of the vase bears the painted mark “W. DE. MORGAN. / FULHAM. / F.P.”—indicating its production at Sands End Pottery in Fulham and the involvement of Frederick Passenger, De Morgan’s trusted decorator who became a longtime collaborator. The number 40 on the right side of the mark suggests that this is a limited-edition piece.

Passenger, along with his brother Charles, played a pivotal role in De Morgan’s workshop. When the Fulham factory closed in 1907 due to De Morgan’s declining health, the Passenger brothers continued to produce ceramics based on his designs, even collaborating with other artists such as Ida Perrin, a great admirer of De Morgan’s work.

Vase, designed by William De Morgan and decorated by Frederick Passenger, late 1890s, glazed earthenware, 13 3/8 × 11 in. Purchased with funds from the Art Collectors’ Council, with additional support from the Adele S. Browning Memorial Art Fund. | The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

De Morgan’s fascination with Middle Eastern designs and colors, which prompted the artist to design this original “Persian” vase, began in the late 1870s. De Morgan was exposed to Middle Eastern tiles and ornamental motifs from Turkey, Syria, and Egypt during his first major commission, the installation of Frederic (later Lord) Leighton’s collection of Damascene and Iranian tiles in the Arab Hall extension of Leighton’s Holland Park home in London.

De Morgan incorporated Middle Eastern influences into his distinctive style of flat, abstract design, exemplified by The Huntington’s vase. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London houses De Morgan’s original design for the vase’s decoration. Rendered in polychrome wash on paper, the drawing depicts “Persian” flowers and foliage in the same vivid colors as those featured on the vase. Drawing inspiration from ancient Syrian and Turkish pottery, De Morgan crafted a harmonious composition of stylized flowers and leaves, evoking an exotic sense of luxury through its intricate pattern, which skillfully combines symmetry with variation. The flawless correspondence between De Morgan’s design and the finished vase highlights the exceptional craftsmanship of Frederick Passenger. Their collaboration reflects a remarkable synergy, transforming De Morgan’s vision into a tangible work of refined beauty.

Sabina Zonno is the research associate in European art at The Huntington.